Karen Kain: 10 years at the helm of the National Ballet of Canada

- Home

- Features 2015 - 2019

- Karen Kain: 10 years at the helm of the National Ballet of Canada

by Michael Crabb

On July 1, Karen Kain marked her 10th anniversary as artistic director of the National Ballet of Canada, the longest-serving in that role besides founding director Celia Franca. Kain joined the National Ballet as a corps member in 1969 and was promoted to principal rank two years later. In October 1997, at age 46 and after 28 years with the Toronto-based company, Kain gave her official farewell performance. She continued to dance elsewhere until the following fall when then artistic director James Kudelka invited her to become a company artistic associate. Her role was loosely defined — one of her major achievements was a triumphant revival of Rudolf Nureyev’s production of The Sleeping Beauty — but, as part of the senior management team, Kain was able to acquire valuable understanding of the company’s inner workings.

For many observers, she was the obvious heir apparent, but when Kudelka unexpectedly announced his resignation on May 18, 2005, Kain, then 54, insists she had not expected to get the job. However, rather than launch a conventional international search for Kudelka’s replacement, the board of directors opted for a fast-track process and polled a variety of leading figures in the dance world, all of whom suggested that Kain was the obvious and appropriate candidate. Her appointment was officially announced on June 23, 2005, effective one week later. It was a baptism of fire because the National Ballet was facing a major operating shortfall and among Kain’s first and most unpleasant tasks was to find ways to rejig the 2005-2006 season in order to save money. The company was also facing the uncertainty of how its move from the 3,200-seat Hummingbird (now Sony) Centre in September 2006 into the newly opened 2,100-seat Four Seasons Centre opera house would affect company finances.

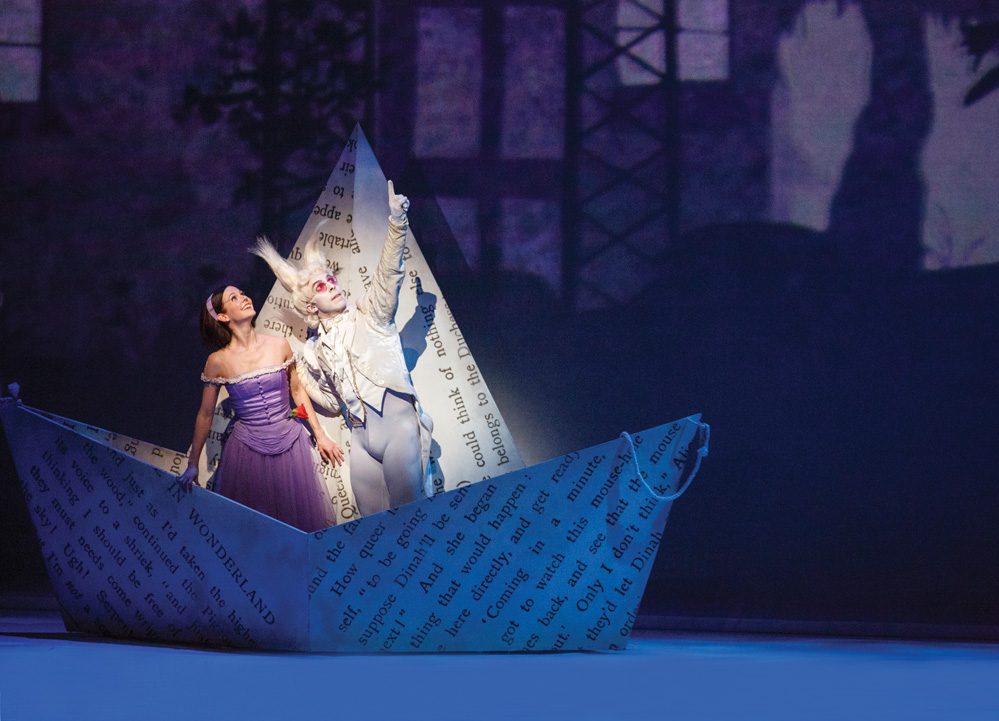

The National Ballet successfully surmounted these challenges as Kain pursued her artistic mission. By general agreement her directorship has revitalized the company. It dances better than ever in a repertoire that has been enriched and broadened with a diversity of new works, some acquired from outside, but many specifically commissioned by Kain. She has presented two all-new, all-Canadian triple bills and garnered huge international interest — and touring opportunities — with A-list choreographer Alexei Ratmansky’s new staging of Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet. Similarly, the company’s co-production with Britain’s Royal Ballet of Christopher Wheeldon’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a deal that gives the National Ballet several years of exclusive North American touring rights, has proved a major success. This November, in another co-production arrangement with the Royal Ballet, the company will dance the North American premiere of Wheeldon’s Shakespearean adaptation, The Winter’s Tale.

Dance International columnist Michael Crabb spoke with Karen Kain about her first decade as artistic director and plans for the future.

Michael Crabb: As you reflect on your work so far, what gives you the most satisfaction?

Karen Kain: When I started in 2005, I set three major goals: to raise the level of dancing, diversify the repertoire and get the National Ballet touring internationally again. It’s been a team effort, of course, and I believe we’ve gone a long way toward achieving these goals and will continue to make progress in these areas. I’m particularly proud of all the new work we’ve presented, which makes the company more interesting for our home audiences and to foreign presenters. We’ve returned to Los Angeles and London after many years, as well as New York and Washington, D.C.

MC: Why has international touring been such a priority for you?

KK: Canadian artists of all kinds want, quite naturally, to be part of a larger world. A ballet dancer’s career is relatively short and although it’s great to have loyal audiences in Canada, dancers want to be seen in the world’s major dance centres. I know that from my own career. I was incredibly fortunate to start out during the “Ballet Boom” and at a major turning point for the National Ballet when Celia Franca made the difficult and as I now see incredibly selfless decision to produce Rudolf Nureyev’s The Sleeping Beauty in 1972. She wanted to take the National Ballet to the next level, but it meant, because of the sheer force of his charisma, effectively turning the company over to Rudolf. We young dancers thought it was fantastic and very exciting, going on those Sol Hurok-produced tours with Rudolf to the Met in New York and across North America, but it must have been hard for Celia. It’s a different world now and I don’t think any company can hitch its wagon to a particular superstar, and there are no more Huroks. Touring has become very difficult and expensive. I knew I couldn’t replicate the experience we had 40 years ago, but, still, despite the challenges, I felt we had to explore what was possible. We’d been almost totally left out for too long. Now, we’re part of the conversation in the ballet world again.

MC: I imagine the repertoire you’ve added has played a major part in this?

KK: Yes, exclusive repertoire is crucial. International audiences don’t want to see the National Ballet dancing what everyone else does. But people also have to know that the dancing itself is at a high level, which is why I’m such a stickler for standards.

MC: So far, Ratmansky’s Romeo and Juliet and Wheeldon’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland have been very successful calling cards for your company. Was that part of your strategy early on?

KK: By the time I started in this job, Alexei was already making a name for himself as a choreographer and was director of the Bolshoi. I’d never met him during his years dancing with the Royal Winnipeg, but I watched what I could of his choreography on DVD and felt it was important to start a relationship with him, which was easier after he quit Moscow and made American Ballet Theatre in New York his base.

As for Chris Wheeldon, his reputation was spreading quickly and even before he launched Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company in 2006, I wanted him to work with the National Ballet. I thought if he saw us dancing his work I might be able to get him to make something for us. So, we presented his Polyphonia in 2008 and he was delighted. You’ve probably heard the story and I’m paraphrasing, but he told me no company had danced it better, which presumably included New York City Ballet where he created it. Later, when I approached Chris about a new work he told me about his plans for Alice at the Royal Ballet and said why not talk to Monica Mason, who was then director. That’s how our co-production relationship started.

MC: Clearly, Wheeldon was happy with the result because soon you’ll be dancing The Winter’s Tale.

KK: With all his connections, he could have offered Alice to anybody, but he’s told me that what he loves about the National Ballet is the way it has all of that North American athleticism, but at the same time has the ability to portray characters in the British tradition, which is something that’s been passed down in the company from Celia’s day. He just didn’t believe any other North American company had these attributes, which were exactly what Alice needed.

MC: I imagine commissioning new work can be a bit stressful because you can’t be sure how it will turn out.

KK: Tell me about it! It’s very stressful. You can never be sure. And you have those awful moments when you’re looking at something you’ve commissioned in the studio and it seems like a disaster and wonder how it’s ever going to work onstage. And, conversely, there can be something that looks pretty fantastic in the studio and then for some reason never quite translates to the stage. But if you worried too much about the uncertainty you’d never do new work. So, I just try to be brave, but, if possible, not foolish.

MC: I guess one could say you’d been shadowing James Kudelka for almost seven years before you succeeded him as artistic director, so I assume you felt well prepared when it happened.

KK: I don’t think I was prepared at all. For one thing, whatever other people might have been saying, I had no idea I was going to get this position. It’s true I’d learned a lot working under James and sitting in meetings, learning about planning and how to balance the costs and what makes what possible. But when the mantle actually rests on your shoulders and the buck stops at your desk, it’s entirely different. It’s not theory any more but the real thing — and it can be incredibly stressful. Every choice and decision you make has repercussions and they can be wonderful or terrible, and you just don’t know at the time.

MC: From talking with other artistic directors over the years I gather that letting dancers go can be really tough.

KK: I’d agree with that, particularly being someone who truly hates the thought of hurting someone’s feelings. And I didn’t arrive in the job as an outsider. I knew so many people who’d been my friends and colleagues, some for many years. I’d shared dressing rooms with and socialized with them. Then, suddenly, I’m the boss. Even so, I knew a lot of hard choices had to be made and I’ve come to terms with it. I’ve always tried to be honest, but I think I’ve become more direct. I try to let dancers know sooner rather than later if I don’t see it working out. But I also tell them they have the opportunity to change my mind, and some have. But it’s still the thing you’re most likely to lose sleep over.

MC: What about the pleasant things?

KK: I’m a big fretter. Anyone who knows me will tell you that. So when something you were a bit unsure of works out just as you’d hoped, it feels amazing. The other thing that gives me great satisfaction is watching the progress of our dancers, seeing the young ones blossom. When I see the talent that’s coming up and what it means for the future of the National Ballet, it makes me very happy.

MC: A feature story about you in a local lifestyle magazine last March referred, I thought a little unflatteringly, to your “naked ambition.” How did you feel about that?

KK: I’m not going to comment on that article. We’re always very grateful when the company gets written about. But I will say this. I have tremendous ambition for the National Ballet of Canada. I believe every director of the company has had that, Celia the most, and she started with the least and built it up. I’ve been around the National Ballet now for 46 years and I care about the company very, very deeply; so, yes, I am ambitious and will keep pushing for better dancing, more and more exciting repertoire and more touring.

MC: Karen Kain, thank you very much.