Resilience on the Prairies: Alberta Ballet finds new relevance at 50

- Home

- Features 2015 - 2019

- Resilience on the Prairies: Alberta Ballet finds new relevance at 50

by Kate Stashko

As the lights go down on Alberta Ballet’s first technical run of Jean Grand-Maître’s Romeo and Juliet at the Northern Alberta Jubilee Auditorium, the air vibrates with that combination of tension and excitement that comes with finally getting a work onstage after endless hours in the studio. As the start-and-stop run progresses, Grand-Maître’s voice echoes over the PA system, providing notes and corrections on everything from lighting and sound cues, to dancers’ spacing and the specific placement of their hands on the set. No detail is left unnoticed. The dancers are equally meticulous and responsive, every moment used to perfect a relevé arabesque or discuss spacing and timing with one another.

Grand-Maître, who is also the company’s artistic director, is demanding; there is no doubt about that. But his tone is warm and understanding. He’s been a performer, too, and knows how difficult it is, so he continually watches out for safety and comfort onstage. The sense of teamwork is palpable, which provides the first clue as to how the company has arrived at its 50th anniversary season.

As I watch the dancers move through the complicated choreography and deal with the changes and challenges that arise in a technical rehearsal, it is clear that this is not the Alberta Ballet of the 1960s. The company’s technical skill has skyrocketed since its early days, now boasting classically trained dancers from around the globe. And yet its pioneering spirit has remained intact. Its artists are some of the hardest working and most ambitious you will ever see on a Canadian ballet stage, possessing the same work ethic for which Albertans are widely known.

Alberta Ballet has its roots in Ruth Carse’s performing group, Dance Interlude, which toured Alberta and was later renamed Edmonton Ballet, and then, in 1966, Alberta Ballet. When, in 1975, Carse transitioned to working exclusively for the School of Alberta Ballet, the company moved through several artistic directors and eventually merged with Calgary City Ballet in 1990.

Tamara Bliss, director of the University of Alberta’s Orchesis Dance Group, remembers Alberta Ballet in 1993, when she arrived in Edmonton from New York. The company was under the artistic direction of Ali Pourfarrokh. “I thought Alberta Ballet was a talented company and I enjoyed their energy and diversity in choreography,” Bliss says. “Although Ali was probably not the most accomplished choreographer, he brought in others who were exciting and contemporary.” It was a big deal for the small company to bring in Peter Pucci, former Pilobolus dancer and a musical theatre choreographer from New York, in 1994, Bliss remembers.

When Mikko Nissinen took over in 1998, he brought Balanchine works into the repertoire, which marked a major milestone for Alberta Ballet. But many saw the Finnish director’s choices as a move backward, limiting the company’s repertoire. However, Nissinen began a major shift toward a more technically skilled group of dancers, and this contribution paved the way for his successor and current artistic director Jean Grand-Maître.

Grand-Maître took the reins in 2002, making the 2016-2017 season his 15th with the company. Grand-Maître, from Quebec, had a brief performing career with Ballet British Columbia and Theatre Ballet of Canada, before working as a freelance choreographer, making works for companies such as Paris Opera Ballet and Stuttgart Ballet, as well as several major Canadian companies. He remembers that, when he arrived at Alberta Ballet with its dual bases of Calgary and Edmonton, “There were a lot of people in the community who cared about the company. As long as we worked hard and produced something that was committed, I knew the local audiences would respond well. Albertans are very ambitious, and, in those days, anything seemed possible.”

Grand-Maître was also acutely aware of the solid foundation Nissinen had laid, providing him with strong, versatile, classically trained dancers who were as ambitious as he was. He felt Nissinen’s programming had been solid, and that the dancers knew what was expected of them. But, he adds, “Mikko’s was almost an American way of approaching a ballet company, and I wanted more of a Canadian soul. I wanted to introduce more Canadian choreographers; I wanted to infuse the work with something that gave us a unique identity. I just thought there was a better way to connect with our community. So that was one of my challenges.”

The other obvious challenge of directing a ballet company in Alberta is, of course, the volatile nature of its energy-based economy. All art forms demand that artists consider their context, and Grand-Maître quickly learned that he and his company needed to be ready and able to adapt to the fluctuations in finances and audience sizes. “I knew we needed the classical ballets to survive, but I came to the rapid conclusion that we had to, as they say on Wall Street, diversify our portfolio,” he says.

This led to the presentation of family-oriented productions (Grand-Maître’s Cinderella), dramatic works for an adult audience (Grand-Maître’s Romeo and Juliet and, in a company premiere, Stanton Welch’s Madame Butterfly) and, in 2007, the first in a series of pop ballets by Grand-Maître. The Fiddle and the Drum, for example, was set entirely to a score of Joni Mitchell’s music. Mitchell, a fellow Albertan and somewhat of a recluse, came out of hiding to help create this new work, which eventually successfully toured North America. Pop ballets became not only a way for Alberta Ballet to draw a new, younger audience, but a means of collaborating with fellow Canadian artists, including Sarah McLachlan and (another Albertan) k.d. lang, in addition to international pop legend Elton John.

Some criticized Alberta Ballet for this move, accusing the company of “selling out” their art form in order to fill seats. But in an artistic climate that sees ballet struggling to maintain its audiences, like every other performing art form, can we criticize a company that is keeping the form relevant and current, and expanding its audience to record numbers?

In October 2015, when I attended a remount of Balletlujah! (Grand-Maître’s k.d. lang pop ballet), I walked into a packed house, and the performance ended with a standing ovation. Ballet is alive and well in the Prairies, and this is in no small part due to the innovation and resilience of Alberta Ballet.

Resilience is the ability of an object to return to its original form after being stretched — an elasticity of sorts. Perhaps resilience in today’s challenging artistic climate is returning to the form in a slightly different way, adapting and mutating as the context demands.

The company’s foray into pop ballets has certainly placed it in a more financially comfortable position that has allowed for expansion in several other directions, both artistically and operationally. In 2009, Grand-Maître created his version of Romeo and Juliet, and, in 2012, the company mounted Swan Lake for the first time, choreographed and staged by former American Ballet Theatre dancer Kirk Peterson after Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. Grand-Maître notes that mounting the classics is no small feat, due to the astronomical costs of costumes and set, and the huge amount of rehearsal time necessary to prepare these works. He considers the company’s Swan Lake one of the major milestones of his time as artistic director, and is proud to have joined the ranks of other Canadian groups producing on this scale.

Alberta Ballet has also been able to continue Up Close, a program that nurtures its own emerging choreographers. Nearly every season, a dancer from within the company has a platform upon which they can create with the company dancers and have their work presented within Alberta Ballet’s regular season; past artists have included Sabrina Matthews and Yukichi Hattori. Up Close sells out nearly every year, indicating that Albertan audiences are hungry to see new work in an intimate setting.

In 2014, Alberta Ballet launched its youth bridging company, AB Ballet II, which doubled in size in its second season. Participants receive an opportunity to work at a professional level, to train and perform with company dancers, and be paid an honorarium, while the company benefits from occasionally having a larger cast that facilitates mounting large-scale classical works. AB Ballet II also fulfills an important role in the company’s outreach efforts, travelling to smaller centres around Alberta and performing throughout the public school system, helping to nurture a future generation of balletgoers.

When I sat down with dancers Laura Vande Zande and Kelley McKinlay, I was again reminded of the ambition and work ethic that are necessary for a dancer to thrive, especially in the Albertan context. They must derive satisfaction from knowing they are playing a significant role in bringing ballet to audiences that may otherwise be isolated from this art form.

“Working in Alberta can have kind of a bubble effect,” says Vande Zande, a Calgarian who is entering her fifth season with the company. “We don’t see as much here as people living in other cities can. But, because of those limited opportunities, people come to see our shows.”

When asked why she chose Alberta Ballet, Vande Zande notes that she saw it as one of the most accessible dance companies in Canada, with a good mix of classical and contemporary work. “After seeing them perform, this was the company in which I could visualize myself working. It’s a very good fit for me.”

McKinlay says, “I love living in a city where art is not the main focus because it’s a real challenge and you have to put in that much more effort to get the work out to the public. Of course, there are times I wish this was a place where people go [to the ballet] because that’s the social norm, but I’m also very happy that it’s not. I love the challenge.”

In his time at Alberta Ballet, McKinlay specifically notes that the addition of pop ballets to the repertoire “sparked an era of dance that attracted new audiences and was a huge turning point for Alberta Ballet.” He adds, “The company had to look at the city we live in, the country we live in, and the time we live in, and really be relevant.”

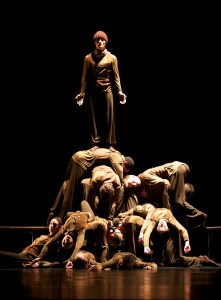

That resilience is something Grand-Maître sees as one of the company’s major strengths, along with the work ethic and ambition of the dancers and artistic staff. It is with this winning combination that Alberta Ballet enters its 50th anniversary season, which includes the company premiere of Ben Stevenson’s Dracula, a presentation of New York’s Pilobolus, and a new work by Grand-Maître to the music of Gordon Lightfoot. These are the season anchors for which the company has become known: dramatic contemporary ballets, a notable international group and its own well-loved pop ballets. The company has discovered a formula that challenges its dancers and engages its audience, and this willingness to adapt to their context is one of the reasons Alberta Ballet is still dancing.