St. Petersburg: Fall 2016

- Home

- City Reports 2015 - 2019

- St. Petersburg: Fall 2016

by Laura Cappelle

There is a special joy in seeing an upstart company or festival fulfill its promise, and St. Petersburg’s Dance Open has done just that. Last spring, it celebrated its 15th anniversary, rebounding from budget cuts to present a satisfyingly full program, geared toward recent creations. The Vienna Ballet returned, while Dresden’s Semperoper Ballett and the Slovene National Theatre Maribor Ballet appeared for the first time … where else would such a range of ballet companies appear together?

At the Alexandrinsky Theatre, a venue with a medium-sized stage, the Semperoper Ballett showcased its strong affinity with neoclassical creation under director Aaron S. Watkin. Tanzsuite, created in 2014, deserves more exposure, for this witty exploration of ballet’s courtly origins is one of Alexei Ratmansky’s best short works to date. Pontus Lidberg’s voice was less clear in Im Anderen Raum, which sets its dancers wandering through dreamlike spaces with standard angst.

Two days later, Edward Clug, the director of Maribor Ballet, presented his latest creation, Peer Gynt, which premiered in Slovenia last November. The Romanian-born choreographer, at the helm of the company since 2003, has been able to experiment and shape the company’s style while creating works on the side as well for the likes of Stuttgart Ballet.

Peer Gynt is a tall order for a narrative ballet. Ibsen’s play is convoluted and episodic, with surreal scenes, a story that involves extensive travelling, and encounters spanning the entire life of the eponymous hero. It was a brave choice on Clug’s part; while not fully successful, his ballet manages to condense a lot of material and convey some of its existential despair in two short acts.

The sets by Marko Japelj are simple yet effective. In Act I, a circular platform allows Clug to economically represent changes of scenery, from the wedding of Peer’s friend, Ingrid, to the trolls he comes upon. The mysterious girl in green who lures him to their kingdom transforms into a troll herself by means of an ingenious costume by Leo Kulaš. When she turned her back to us and flipped her hair up to reveal a mask, her “real” appearance was revealed, her ungainly backward walk an unsettling effect fit for the character.

Act II brought yet more strange adventures, including the Bedouin character Anitra, who steals from Peer Gynt by rolling him up in a carpet and pulling his pants down. It’s a testament to the presence of Russian guest artist Denis Matvienko that Peer Gynt came across as a coherent character, lost, melancholy yet unable to change his ways. Clug shrewdly chose a score by Edvard Grieg, the Norwegian composer who created the original music for the premiere of Peer Gynt in 1876. Supplemented by other pieces, it sets the atmosphere beautifully, and Maribor Ballet did justice to Clug’s vision with complete commitment to his earthy, modern style.

The closing Dance Open Gala was restored to its full glory, complete with the awards ceremony that was cut last year. Its most enjoyable aspect has always been the diversity of the excerpts presented, most of which stray far from the usual repertoire of warhorse pas de deux. This edition brought a welcome duet from Ted Brandsen’s Mata Hari, which premiered in Amsterdam in February. Anna Tsygankova (ably partnered by Artur Shesterikov) earned the Ms. Expressivity award for her quietly moving, unostentatious performance, making the utmost of Brandsen’s elegant lifts.

Stuttgart Ballet’s Alicia Amatriain and Jason Reilly worked their way through a slinky creation by Eric Gauthier called Punk Love. Its violent undertones — Reilly holding Amatriain by the neck, costumes consisting of tattoos on a nude unitard, a hint of Frankenstein about their relationship — lacked direction, though showed the pair’s physical command.

The Mikhailovsky’s Irina Perren and Marat Shemiunov conjured feats of Soviet acrobatics in Fyodor Lopukhov’s The Ice Maiden, while Remi Wörtmeyer presented a witty solo from Hans van Manen’s Five Tangos. After an impeccable Satanella pas de deux with Dinu Tamazlacaru, Iana Salenko returned in a contemporary pas de deux by Raimondo Rebeck, Not Any More. It offered a neat visual trick — Salenko running in the air, held by her partner (and husband) Marian Walter with the help of a hook under her costume — but was mostly generic emoting.

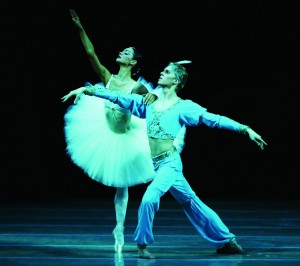

The evening’s Grand Prix was awarded to the Bolshoi’s Olga Smirnova and Semyon Chudin for their pristine form in Marco Spada. The People’s Choice Award went to veteran superstar Manuel Legris, who, in addition to bringing his Vienna Ballet to the festival, performed an excerpt from Roland Petit’s La Chauve-Souris with Maria Yakovleva. Legris brought Charlie Chaplinesque flair to the slapstick scene; he rarely performs now, and his inimitable personality is still missed onstage, nowhere more so than in Paris.

A trio from different companies — Oxana Skorik, Matthew Golding and Tamazlacaru — closed the evening with Leonid Lavrovsky’s complete Walpurgis Night. Skorik is very tall for the female role and lacked some of the attack required, despite her technical strength. Tamazlacaru proved a true virtuoso, as Osiel Gouneo had earlier in the evening, with his ability to slow down turns on a dime in Don Quixote.

The excellent Compania de Flamenco de Úrsula López brought a little relief from the classical technique on display, as did the Argentine-born Lombard Twins, Martin and Facundo, who interpreted Astor Piazzolla with a rousing mix of tap, street dance and Michael Jackson-style moves.

Across St. Petersburg, the Mariinsky presented a healthy mix of classical fare. The season’s main premiere, Yuri Smekalov’s The Bronze Horseman, was reportedly a successful neoclassical reinvention of the Soviet ballet, with roles for a large number of soloists and a recording is in the works; but the main story was the changing of the guard happening with young dancers taking on leading roles. Leading the charge was the sprightly soubrette Renata Shakirova, who graduated from the Vaganova Academy last summer and has already danced Don Quixote, Romeo and Juliet and a long list of other roles.

Last April, another up-and-comer was tested in a plum part: Vitaly Amelishko, who joined the company in 2014 and made his debut as Solor in La Bayadère. He acquitted himself well, with plush jumps and technical ease, though some stiffness is still visible in his stage manner. As a tall dancer, however, he is bound to be a solid addition to the Mariinsky’s soloist ranks in the future.

The rest of La Bayadère’s cast was merely average by the company’s standards. Anastasia Kolegova is a more natural Gamzatti than Nikiya, and brought little pathos to the role of the temple dancer, despite lovely form. Yekaterina Chebykina, who joined from Kiev, lacks her Vaganova-trained colleagues’ refinement, and made a muted impression as Gamzatti. The performance’s true glory was the corps de ballet, at full strength on its home stage, and leading the way from the Himalayas with heavenly beauty in the Shades act. At their best, they are peerless, and enough for audiences to go home happy.