New York City: Spring 2017

- Home

- City Reports 2015 - 2019

- New York City: Spring 2017

by Robert Greskovic

For two weeks at New York’s downtown Joyce Theater, a converted movie house, the Lucinda Childs Dance Company took to its somewhat limited stage. Wider than it is tall or deep, with no orchestra pit and a plain brick back wall complete with an indentation that once held a projection speaker, the Joyce’s performing area can be a challenge to proscenium-styled work for both performers and audiences. Childs’ work, however, looked well situated here.

The first week’s program, Lucinda Childs: A Portrait (1963-2016), proved a neat overview of the dancer and dancemaker who came of age in the 1960s when what we call postmodern dance was being explored.

The works in the first half played out in nearly precise chronology, from 1963 to 1977. The earliest, Pastime, which stands as the first work in Childs’ choreographic chronology, was initially a three-part solo for Childs. For this rare restaging, it was apportioned to three company dancers, who each duly displayed the deadpan wit of the choreography. Pastime was led off by statuesque Caitlin Scranton, whose striking dark looks are reminiscent of Childs’ own. Scranton remains mostly stationary in profile stance as she dangles a lower leg and animates its foot as if she were a flat, cutout, hinged mannequin. All the while, Philip Corner’s soundscore of gushing, rushing waters acts as accompaniment.

Katherine Helen Fisher follows, as a bathing beauty flexing a sleek leg and foot skyward, while contained in a stretch-fabric affair with the character of a bathtub. Finally, Anne Lewis performs mostly folded over forward on her hands and one leg until she is left balancing only on her leg with her other limbs angled away from her.

A memorable trio of dances capped part one of Portrait. These three studies each showed how Childs advanced from the delicately witty aspect of Pastime toward minimalist dance, which has more or less since dominated her interests. These dances, all without sound accompaniment and all costumed in sleek, cream costuming of leotard-topped, high-waisted slacks, which became a signature Childs’ look, demarked the stage with patterns and rhythms that bring the viewer into their pulsing, repeated locomotions.

Katema from 1978 delivers a crisscrossing set of striding and pivoting paces for two pairs of women. The X arrangement of their paths gets accentuated more at their end points than at their central point of crossing. Childs’ manager emailed me the following comments about this dance, named for a place on Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts, where, “Every few hours, the tide changes direction. Instead of having one opening to the sea, it has two openings. Currents can be rising from two directions, or falling when the current is moving either direction.”

Radial Courses (1976) and Interior Drama (1977), the two other cream-costumed dances that followed, each revealed rarified motor energy that drew attention to its simply varied movements.

Radial Courses has four men on a determined mission of repeatedly coursing the stage in this direction and that, building up to a quiet haste that prompted smiles from the engaged onlookers. While each dancer played his part scrupulously, I was especially taken by the fleet and buoyant way in which Vincent McCloskey took to the little hop/skip/dart sequence that intermittently elaborated the choreography’s delicately frantic pacing.

Interior Drama showcases six women, who form a recurring V arrangement, facing the audience with advancing, receding and side-directed impetus built from its ongoing strides, some set as if marking time with legs swinging like bell clappers. Engagingly, the cast’s two smaller women define little pooling paths as if, perhaps, they were the independent engines on some V-shaped aircraft.

The second half of Portrait showed dances of later vintage, all with musical accompaniment. The 1993 Concerto, to Henryk Górecki, showed more open, air-filled emphases, with Childs’ familiar, carefully calibrated paces set more freely and expansively. Górecki’s music, metallic and driven, added piquancy to the austere dimension of it all.

A segment from the 2010 Lollapalooza (to John Adams), made originally for students, looked thin. Like Lollapalooza, the 2015 Canto Ostinato (to Simeon ten Holt’s burbling music of the same name) involved brief moments of partnering, which only recently became a choreographic interest for Childs. It had a sometime pleasant mating game air, but in the end felt unfinished.

Capping the program, however, the new Into View, to The Sun Roars Into View by Colin Stetson and Sarah Neufeld, showed Childs’ arriving, if perhaps not yet fully arrived, at a new point of exploration. Here 11 dancers, an odd number for a dance that has its cast catching itself into coupled configurations on its shifting and pulsing ways across and over the stage, beguiled the eye with travels that felt spiritual as they took place in the glow of John Torres’ halation of light emanating from a pinhole point on the background.

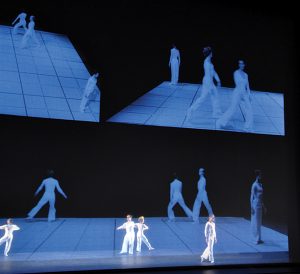

Finally, occupying the second week was what is arguably Childs’ most iconic work: Dance, the inspired collaboration from 1979, trimmed back to 60 minutes running time. In it, she teamed up with visual artist Sol LeWitt for his overspreading décor of film, with minimalist master Philip Glass for his dryly celestial score, with Beverly Emmons for her counterpoint lighting choices and with costume designer A. Christina Giannini for her trim versions of Childs’ tailored uniform look. The much-admired Dance has been rewardingly revived on occasion, and this restaging was another welcome one.