Breaking the Sound Barrier: Antoine Hunter and Cai Glover deftly navigate dance and deafness

- Home

- Features 2015 - 2019

- Breaking the Sound Barrier: Antoine Hunter and Cai Glover deftly navigate dance and deafness

by Toba Singer

When I saw Oakland Ballet’s Nutcracker at the age of five, it wasn’t about the développés. It was about the gestures and communication,” says Antoine Hunter, artistic director of Urban Jazz Dance Company in San Francisco. Hunter, who is Deaf,* grew up feeling as if he were being held hostage to a hearing world — uncaptioned TV cartoons made no sense — but that feeling vanished when he saw Nutcracker. “Others laughed, I laughed, everyone was laughing together at the tipsy uncle onstage.”

While learning American Sign Language (ASL) as a child, Hunter began to realize that the deaf and the hearing were two separate cultures. Later, when he began dance training — first at Oakland’s Skyline High School, which has an extensive performing arts program, and then with the Paul Taylor Dance School, among others — he recognized that the steps and gestures of dance could act as a bridge between them.

Once he started teaching dance, Hunter worked to create an ASL-based vocabulary for his integrated classes. He developed many of his ideas as a teacher when he realized that the deaf dancers he worked with tended to possess interpretive depth many hearing dancers struggle to attain. Convinced that words cannot fully express feelings, Hunter believes, “Hearing people wait for words to explain. Deaf people go directly to expression.”

His teaching took off, and members of Savage Dance Company, a ballet-based jazz group with whom he has performed, began taking his intermediate-level jazz class at Berkeley’s Shawl-Anderson Dance Center. Their artistic director hoped it would help them find emotional eloquence through Hunter’s emphasis on opening the body through the spine and hips, so that feeling can flow from the centre outward.

Often, hearing people assume vibration is a deaf person’s only way into music, but Hunter also credits subtle cues from less obvious indicators, such as shaking stage lights signaling that a recording has started. “My great-grandfather played jazz on a record player. I could feel a ‘snap, crackle and pop,’ like I saw in the Rice Krispies cereal commercial on TV,” he says. Though Hunter couldn’t hear the instruments, he saw their impact on others. He reports staring at album cover illustrations to internalize the feelings they conveyed.

Among his favourite songs is Whitney Houston’s I Will Always Love You, because of the directness of the lyrics. In 2015, he used Call Me, Maybe by Canadian singer/songwriter Carly Rae Jepson when he was choreographing, using roller skates, for a Portland children’s project. The performers included Ryan Lane, who plays Travis, one of several deaf characters in the U.S. TV series, Switched at Birth. Hunter says, “I set it in 24 hours, and worried it would end up cheesy, but it was colourful, capturing the free feeling I was after.”

Generally, lyrics introduce stress, and Hunter prefers instrumental music — he mentions Seven Steps to Heaven and High Speed Chase, both by Miles Davis — where he has freedom to do what he wants without being bound by the words.

Recent commissions for San Francisco companies, such as All Blues to Deafhood (ODC Theater), Body of a Black Man (AfroSolo Theatre Company) and The Finest (Dance Mission Theater), are characterized by periods of silence, so the audience can experience what it is like to be deaf, and include gestures from ASL, integrated into jazz, modern and classical ballet movement.

Cultural identity is the core value of the annual Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival that Hunter inaugurated in 2013 and continues to produce. Held this year in August at San Francisco’s Dance Mission Theater, it is the nodal point for Hunter’s embrace of movement, teaching, choreographing, mentoring, commitment to social advancement, outreach to the Black community, and encouragement of deaf and hearing dancers from other countries, which have included Turkey, Mexico, the Philippines and England. Political figures, entertainers, dance artists and deaf agencies attend. The result is an abundance of cultural collaborations.

Cai Glover dances with Montreal’s Cas Public. He lost his hearing to meningitis at age eight, and on his return to school in his hometown of Prince George, British Columbia, couldn’t cope with no longer being able to hear his classmates. So he resorted to “passing,” pretending to understand. Luckily, at that age, interactions were mostly via games and play, with plenty of visual cues.

A cochlear implant in his right ear at age nine brought a glut of auditory information, but the device did not always work. So Glover continued to pretend he was “getting it” and sought to hide deaf traits because he didn’t want to seem different.

At age 10, he accompanied his sister to a local Nutcracker rehearsal and immediately saw dance as a way to express what he could not say with words, and joined the cast. The following year, he began to take ballet classes and, at 18, moved to Vancouver to study at Pacific Dance Arts.

Dance training presented its own problems. While teachers couldn’t expect Glover to follow music on his own, neither did they want him to mimic others to reconcile the counts. Without realizing it, to build a platform for independence he developed what he calls an “inner metronome,” constructing a melody in his head to correspond with what he saw dancers doing in class.

Now that Glover is a professional, the fact he cannot be persuaded by the music can appeal to contemporary choreographers, some of whom have a keen interest in discovering and celebrating nuances that a deaf dancer might introduce, complementing music in sometimes unexpected ways. In the contemporary dance world, Glover says, “There is a reverence for avoiding obvious interpretations.”

At Atlanta Ballet, where he started his professional career, Glover was too young to realize he could make certain demands. He was still trying to pass, confused about how to acknowledge the hearing he did have, however intermittent, through his cochlear implant. He believes now that he placed the company in the awkward position of not knowing what help was needed. He also experienced one obvious instance of discrimination, when a ballet mistress insisted he wear a wig “to cover up your thingies,” referring to his hearing aids. He was moved to the back line in the next rehearsal, though felt certain his frontline work had been just fine.

Stage fright can provoke anxieties for any dancer. For a deaf dancer there’s sometimes an out. Glover says he feels most free when his implant processor stops working: “I forget my mortality!” His artistic director at Cas Public, Hélène Blackburn, told him she can tell when it’s on the fritz — it’s when he dances best.

To avoid his needs becoming a focus, Glover is reluctant to slow conversations down, and becomes defensive when someone tries to help, though it can be difficult to follow larger conversations about stagecraft technicalities when they bounce from one thread to another, and where a variety of voice tones tend to blend together. He looks forward to innovative Bluetooth speaker technologies that could make a difference.

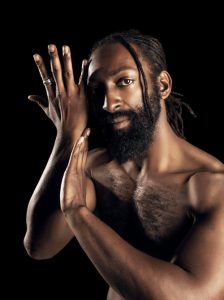

Photo: Damian Siqueiros

Blackburn was the first choreographer to tell Glover that she saw his frustration. Glover says she honoured his difference, convinced it was what made him “so engaging and interesting.” Until Blackburn expressed this, he hadn’t heard such an encouraging point of view from anyone else. On the contrary, he had received compliments for not appearing to be deaf, grooming him for a life spent reaching futilely for “normal.” Blackburn’s words led Glover to respect himself for being authentically perceived, proud of the creative edge being hard of hearing lent to his dancing.

Glover reminds us that disability does not come just from within; much of it is externally imposed. For him, what is disabling is architectural design with no ramps and shows without closed captioning. Culture, he says, demands variety in its artistic expression, and dance can represent a diverse culture embracing difference.

Even ballet, he points out, “isn’t only for kings and queens anymore, and need not only represent royalty and classically determined physical perfection.” Perhaps, he adds, “it’s not about abandoning perfection, but changing our idea of what it means to be perfect.”

Photo: R.J. Muna