Life in the Corps de Ballet: Insights from the ground in North America and Europe

- Home

- Features 2015 - 2019

- Life in the Corps de Ballet: Insights from the ground in North America and Europe

by Jennifer Fournier

For classical ballet, an art form born in the court of the aristocracy, rank is foundational. Hierarchy is embedded in the canonical works, populated as they are by peasants and gypsies, and dukes and princesses, and in the companies themselves where the principal dancers quite literally reign, onstage and off. But while the spotlight may shine more brightly on the stars, a company’s reputation is won or lost by the artistry and standard of dancing by its corps de ballet.

To find out more about the challenges and rewards of life in the corps de ballet, I spoke with several corps dancers at a variety of stages in their performing careers — all fine artists in their own right — from large ballet companies in North America and Europe, as well as two ballet mistresses.

Almost all dancers start their career in the corps, but increasingly they perform with a company for some time without any guarantee of being hired full time. Katie Bonnell, a dancer in her mid-20s at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, danced first as an aspirant while still in the company’s school and then as an apprentice for a total of four years before she was offered a full-time corps contract last year.

Rebecca Rhodes, a 28-year-old senior corps dancer at San Francisco Ballet, also spent years as a trainee, working on repertoire during the day and performing at night with other trainees all over the Bay area, and augmenting the company in larger productions when needed. She was only one of two of the 11 trainees to get a coveted contract with San Francisco Ballet as an apprentice in 2009.

Lise-Marie Jourdain of the National Ballet of Canada and Laurence Laffon of Paris Opera Ballet, both in their late 30s, began their careers at the Paris Opera where dancers apprentice for anywhere from six months to a year before being offered a tenure-track position. Unlike many companies where dancers can join at the level of principal or soloist, Paris Opera Ballet promotes, with rare exceptions, from within and all dancers must begin in the lowest of five designated ranks, quadrille. (To give some sense of the complex hierarchy at Paris Opera Ballet, there are three ranks forming the corps de ballet: quadrille, coryphée and sujet.)

Lower-paying apprenticeships may make good financial sense for companies that need to keep overhead low, but the reality is even the finest ballet training doesn’t fully prepare a dancer for the demands of a professional corps. Jourdain, who has 22 years of experience, recalls that in her first years at the Paris Opera she would understudy several women in one ballet: “It was stressful dancing a different person every night, but it was also a very good place to learn how to dance in the corps de ballet.”

Amanda Clark, a senior corps member of Seattle’s Pacific Northwest Ballet, called dancing in the corps “a steep learning curve — as a student the process is much slower because you spend a whole year rehearsing for a performance. Suddenly you have to learn how to judge a line and know not just the count but the right part of the count — and it all has to become innate.”

Laffon, now an accomplished sujet who has danced with the Paris Opera Ballet for 20 years, likened the process of learning the classics to a rolling train that has long since left the station, which the new dancers “have to catch.”

Ballet mistresses are crucial to the process of achieving the uniformity necessary for the classics. Their jobs are especially difficult where dancers are drawn from different schools around the globe. Caroline Gruber, former principal dancer and current ballet mistress of the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, says her job is to bring the ballet to life: “I don’t want rows of dancers without interpretation — but I do want oohs and aaahs at the uniformity. I work on the turn of the hand, alignment, the way the foot is placed on the floor.”

Lorna Geddes, a veteran of the National Ballet of Canada who danced in the corps for 25 years until she was appointed as assistant ballet mistress in 1984, says she used to coach new corps members privately in the style of the work and help them learn how to use peripheral vision to check the line or height of their arms without moving their head or eyes.

Geddes adds that Rudolf Nureyev, who made regular tours with the company, insisted on full movement from the corps, with lots of bend in the torso and deep pliés. From him Geddes learned how useful it was to watch the corps from the wings to get another perspective, as Nureyev used to do before his performances. “I remember Rudi warming up in the wings during Sleeping Beauty and belting out ‘stretch your feet!’ or ‘wake up!’”

Learning how to handle the intense workload is one of the greatest challenges at every stage of a career. At San Francisco Ballet, for example, there is a four-month season right on the heels of three weeks of Nutcracker. “When you are a principal or soloist, you get nights off, but, in the corps, you are expected to dance every night,” says Rhodes. In her first year with the company, Rhodes developed a stress fracture and was so worried about losing her job, she didn’t tell anyone. “Looking back, I wished I had stopped earlier — I didn’t know you could take time off to let an injury heal.”

Because the corps do runthroughs with every cast of principals, and sometimes don’t have second casts, they risk getting injured before they even get to the theatre unless they learn how to back off before injuries occur, says Pacific Northwest Ballet’s Clark. Pacing yourself is especially hard for corps dancers who undertake soloist roles, because they will sometimes alternate between dancing in the corps in one act, where muscles tighten up from all the standing around onstage, and dancing a solo in the next act, which requires a different kind of physical and mental preparation. Young dancers might assume they will be relieved of their corps work when they have an important solo, but, as Jourdain says, there is an unwritten code: “It would never occur to me to get out of corps work to save myself for a solo,” noting that “as you age it does get harder.”

Laffon, who has three years until mandatory retirement at the age of 42 with the Paris Opera Ballet, worries on days when her body is really hurting that she may not be able to perform classical ballets such as Swan Lake for much longer.

Another aspect of life in the corps, especially in the early years, is the paradoxical feeling of being on your own. Unlike principal dancers who develop intimate professional and personal relationships with coaches, corps dancers are often left to shoulder the challenges of professional development with minimal support from management. For example, after dancing a soloist or principal role, a dancer usually hears from the ballet master or artistic director immediately after their performance — for a corps dancer a cursory, “Good show everyone,” delivered onstage to the whole company, sometimes has to suffice.

Gruber tries to confine herself to positive comments to the group after the performance, saving her individual notes for the next day so as not to ruin the experience of the show.

As dancer Jourdain explains, “You need feedback as an individual, but in the corps there are so many people on every night, so the feedback is delivered to the group. I sometimes feel a bit lost without personal corrections.”

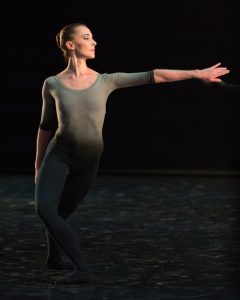

Photo: Karolina Kuras

Although corps dancers have yearly performance reviews, Clark also believes there should be more communication — about artistic choices, casting and performances.

The dancers learn to depend on each other. Mentoring is vital, and all of the older dancers interviewed say that passing on their knowledge is empowering. Rebecca Rhodes says she has taken on a maternal role with the younger dancers, helping them with their soft corns (the bane of a dancers’ existence), for example. She also notes how the atmosphere at San Francisco Ballet has become more supportive over the years; today, principal dancers might point out what they liked about her performance, and even the younger dancers feel free to give such positive feedback.

Jourdain says that although doing three pirouettes and “being on” feels great, the communion with other dancers, often through laughter, is ultimately more memorable. Empathy is as important as a good sense of humour. Clark points out, “You work with so many dancers, some you have danced with for years and some who are new, so you need a strong set of interpersonal skills. When there is tension, you always have to ask yourself — is this person hurting or having a bad day?”

There is certainly tension between the individualistic drive required to become a ballet dancer and the necessity of being a team player as a member of the corps. Especially when they are new, most young dancers dream of moving through the corps de ballet, not remaining in it. Katie Bonnell, who is already getting the opportunity to dance featured roles, exemplifies this attitude: “I’m always going to push to dance more soloist and principal roles. Trying to find ways to stand out in the corps while not looking like I’m making a mistake is a matter of stage presence and work ethic.”

Lorna Geddes, on the other hand, knew right away she didn’t want to be Swan Queen. “You could say, ‘Boy, you lowered your ambitions,’ but I really wanted to dance a lot. I would choose not to have a second cast [in my roles], so I could be on every night!”

To young dancers, Geddes cautions that trying to stand out is a misguided approach. “You are part of a group, you are not ‘you’ trying to outdo the girl next to you with a higher leg or something. If there’s an awful lot of drive in you, don’t use it in the corps where you have to be good within limits.”

So how does a dancer in the corps move up in the ranks? The truth is that in classical ballet, a dancer’s rise is often subject to forces and considerations beyond their control. Performing well in the occasional soloist role is usually the best way to prove yourself, but as Clark points out, opportunities often come when you are juggling your corps role and are at your most overworked and tired.

Yet artistic directors, who play a central role in casting, do often take classwork into account. Peter Boal, artistic director of Pacific Northwest Ballet, teaches company class twice a week as “a way of keeping tabs on the dancers,” Clark says.

Laffon explains that former Paris Opera artistic director Brigitte Lefèvre was not in the studio, but was “with us for performances every night.” The dancers were excited at the prospect that Lefèvre’s short-lived successor, Benjamin Millepied, would be in the studio, but he was there so little and taught class so rarely that he seemed more like an “adjunct.”

After eight years in the San Francisco Ballet, Rhodes says she doesn’t have a “buddy-buddy” relationship with director Helgi Tomasson, but if there is a role she wants she feels comfortable asking him, and if there is something lacking in her dancing he will tell her. By contrast, Jourdain is hesitant about being direct with Karen Kain, at the helm of the National Ballet of Canada. “I have always felt more comfortable working harder to be picked for something than pushing for a role they might not see me in,” she says.

Jourdain’s reticence may derive from her roots in the Paris Opera Ballet where dancers are judged by a panel of internal and external adjudicators in a company-wide concours to determine suitability for promotion. While the dancers decide whether or not to put themselves forward, and can choose one variation of the two required, their performance that day plays an outsized role in determining success. Jourdain admits the system is in certain ways unfair: “Some people never get featured and all of a sudden they are amazing on the day, and sometimes it is the other way around — but it is such a part of the tradition.” Although these examinations strike many as outdated and cruel, they arguably inject transparency and a certain democratic spirit into what can be highly subjective decisions.

When choreographers unfamiliar with a company are invited to set or create work, they often notice things in certain individuals that others miss. Although dancers generally don’t like open auditions, they allow choreographers to see how dancers dance their work — and this process can be to the advantage of the lesser known. Additionally, it can be difficult to cast high-ranking soloists and principals in works where there may not be any featured roles. As a result, many corps dancers have a large contemporary repertoire in the ballets of a wide range of emerging and established choreographers.

Rhodes names her work with Liam Scarlett (she originated a role in Scarlett’s Hummingbird) and Christopher Wheeldon (she has danced in several of Wheeldon’s many works for San Francisco Ballet, including Ghosts and Within the Golden Hour) as highlights of her career because of the opportunity to be part of a collaborative creative experience.

Laurence Laffon says that Pina Bausch, who she met when she was 19 and who cast her in Le Sacre du Printemps, “taught me to push my physical and emotional limits and express my own personality and individuality even in extremely rigorous choreography.”

Photo: Réjean Brandt

Laffon adds that working with Trisha Brown on Glacial Decoy, a work danced in silence, was also a transformational experience. “I learned how movement creates its own rhythm. I felt during the 25 minutes as if I was unspooling a thread from a ball — and the feeling of completely listening to the breathing of the movement and being with the other dancers was magical.”

Jourdain singles out contemporary choreographer Crystal Pite for her generosity and interest in dancers who aren’t “perfect.” “When Crystal cast me [in the premiere of Emergence at the National Ballet of Canada] I thought, ‘Why me?’ and imagined they were going to remove my name from the cast list. But she told me ‘No, it’s yours.’”

Pite’s large group pieces have become a signature and are embraced by dancers eager for work in a more egalitarian vein. Laffon says that Pite’s recent The Seasons’ Canon for the Paris Opera Ballet was an amazing experience because she “makes work for everybody at the same level — and the audience can feel that we are with her and completely invested in the piece.”

Each dancer interviewed is passionate about their career, but it is passion tempered by realism. “I get to do a lot of soloist roles, which are more rewarding and fulfilling, but I am a solid corps dancer,” says Rhodes.

Many said that dancing in the corps was deeply fulfilling, albeit less obviously so than soloist work. “We always envision being in front and doing a solo part as the most rewarding, and definitely you crave artistic and technical challenges, but when I think about the most awesome moments onstage, more of them are in a group,” Jourdain says.

“You would think I’d say Swan Lake was the least rewarding ballet to dance,” says Rhodes, “but whenever we are together, there is a huge feeling of accomplishment from being a part of this big thing.”

Besides Bluebird pas de deux in Sleeping Beauty, Clark told me that her most memorable experiences onstage have been in two works by Balanchine, Serenade (which she danced outdoors in the mountains at Vail, Colorado) and Concerto Barocco — not only because his style feels natural to her, but also because she was dancing with her friends.

Jérôme Bel in his work Véronique Doisneau, an unflinching portrait of a sujet of the Paris Opera Ballet in her last season before retirement, brilliantly captured some of the ambivalence many dancers feel about the corps. Bel seems to provide a fairy tale ending to Doisneau’s career by giving her the opportunity to perform an excerpt from Giselle, a principal role she had long dreamed of dancing.

Except Véronique Doisneau, the ballet, didn’t end there. For her final moments onstage, Bel had Doisneau dance what she referred to during one of her monologues as “the most horrible thing we do”— the section in which the corps becomes, in her words, “human décor” during Swan Lake’s White Swan pas de deux. But without the swans or their Queen onstage, Doisneau, performing steps she had danced hundreds if not thousands of times, showed us how dancing can effortlessly transcend any worldly conception of rank.

It might seem tragic to some that the dream of being a prima ballerina is what draws dancers to large companies where most are fated to dance in the corps de ballet. As a result, many decide to go to smaller groups where there is more mobility in the ranks or no ranks at all. But, in fact, only a handful of principal dancers will perform Swan Queen or Giselle, and many will stop performing those roles after a certain age, while corps dancers (who typically dance in almost every scene) will revisit ballets such as Giselle and Swan Lake over and over again, teaching them to new members of the corps and discovering new things in the music and choreography along the way until, as with Doisneau, these ballets become inseparable from who they are.

One could even say without much exaggeration that because of the huge range of many companies’ repertoires, encompassing the romantic, classical, neoclassical, modernist and contemporary eras, many dancers in the corps are living embodiments of the art form’s history. But such a grandiose claim is not likely to be made by them. Lorna Geddes says it more simply: “In the corps, you don’t get pigeonholed as you do as a soloist where you are either a soubrette or a sylph or a contemporary dancer — in the corps you do different things and different styles all the time.”

Clearly, for dancers who choose to persevere within the corps, they can have careers of unimaginable richness. “In the blink of an eye, it was 22 years. It was a life,” Jourdain says. “And like anything in life you have ups and downs — but you open yourself to other things and grow and stay motivated.”

What about the realization that one will not become a principal dancer? “I dance a lot of contemporary and classical roles and am very happy with that,” says Laffon. “I stayed here yet I’m proud of my friends who have left — that took courage. But after turning 30 I realized my life is in Paris and I love this company. The feeling is good.”

AFTER THE CORPS DE BALLET

Most of the artists interviewed here have considered what comes next once their performing careers are over. Rebecca Rhodes made continuing post-secondary education a priority during her career and while she doesn’t have any immediate plans to retire, she already has a bachelor’s degree and intends to study nursing. Rhodes is married and plans on starting a family soon, noting that typically only soloists and principals have children in her company due to the corps members’ strenuous workload.

Photo: Angela Sterling

Laurence Laffon, like many dancers in the Paris Opera Ballet (where dancers have tenure and periodic sabbaticals), has a husband and children, and last year received a teaching diploma in order to teach when she retires. Having made the decision to stop participating in the internal concours five years ago, she now coaches younger dancers in their solos for that competition. Lise-Marie Jourdain, who is married to a former dancer and has a young child, always knew she wanted to be a teacher and took her diploma at age 21; three years ago she started teaching a little on a regular basis, and will teach when she retires. The only one not yet planning for the future is Katie Bonnell, who is completely focused on dancing — she took a mandatory English course necessary to pursue a degree “only to get it out of the way.”

Not long after my interview with Amanda Clark, who has a master’s degree in international relations, she left Pacific Northwest Ballet to shift her focus to international development and diplomacy. According to the company, she left “very quietly and with little fanfare.” In a farewell note to her former colleagues, Clark said that while she was “sorry for not announcing my decision publicly,” she was “grateful for the opportunity to say goodbye to ballet in my own way.”

Featured photo of San Francisco Ballet’s Rebecca Rhodes (centre) with company dancers in George Balanchine’s Theme and Variations | Photo: Erik Tomasson

Tags: Amanda Clark Caroline Gruber Crystal Pite George Balanchine international dance news Jérôme Bel Karen Kain Katie Bonnell Laurence Laffon Lise-Marie Jourdain Lorna Geddes National Ballet of Canada Pacific Northwest Ballet Paris Opera Ballet Rebecca Rhodes San Francisco Ballet Véronique Doisneau