Venice Biennale: Festival Roundup

- Home

- Reviews 2014 - 2019

- Venice Biennale: Festival Roundup

The Venice Biennale tide lifts all cultural boats, including dance. This six-month-long culturefest attracts international crowds, generates debate, and connects many disciplines and nationalities. Starting her four-year term as the Biennale’s dance director, Montreal choreographer Marie Chouinard programmed 13 troupes, half from Montreal, in 30 shows, films and discussions over nine days at the end of June.

The extremes of dance’s concepts and forms were shown in works presented by the Biennale’s 2017 award winners, American Lucinda Childs (Golden Lion for lifetime achievement) and Canadian Dana Michel (Silver Lion for innovation).

In Childs’ delightful Dance (1979), dancers hopped and turned in horse-and-carriage harmony with Philip Glass’ music. Adding thrust was Sol Lewitt’s background black-and-white video of the original cast performing the same steps, though the live cast frankly showed cleaner lines and lighter turns.

Michel’s 2013 revelatory solo, Yellow Towel, had no music, much stumbling and shuffling, and mumbled texts. Michel portrayed a black woman desperately trying to conform to white society aesthetics, giving authentic voice to a troubled soul.

Humour informed a similarly themed solo by South Africa’s Robyn Orlin, And You See … Our Honourable Blue Sky And Ever Enduring Sun … Can Only Be Consumed Slice by Slice … performed gustily by black actor Albert Silindokuhle Ibokwe Khoza. Initially wrapped in plastic, Khoza cut away his culturally imposed bonds with a knife, implying that radical change necessitates harsh measures.

Khoza’s personage flamboyantly revelled in his ethnicity, revealing himself as gay, vain and imperious, commanding two spectators to wipe his bare body. Vladimir Putin appeared in a funny trumped-up video. “Better dance than make war,” intoned Khoza.

A subtler warning about leader-types was found in It’s going to get worse and worse and worse, my friend, a 2012 solo by Belgium’s Lisbeth Gruwez created with sound designer Maarten Van Cauwenberghe. To prepare, Gruwez studied Mussolini and American evangelist Jimmy Swaggart. Calm ingratiating gestures led to megalomaniacal grandiose sweeping arms.

Compagnie Marie Chouinard appeared in Soft virtuosity, still humid, on the edge. In familiar Chouinardian style, zombie types crisscrossed the stage, tongues flaying, arms pumping. In contrast, Scott McCabe and Clémentine Schindler performed a ballet-type duet. After years of presenting characters as deformed or crippled, Chouinard can nonetheless create emotionally charged “classical” duets. Later, a nude female in a transparent white costume danced an alluring solo. Angel? Seductive devil? Both? The show ended with two dancers wearing painted wings, an intentionally silly note. A multi-faceted work, not fully integrated.

As Biennale dance director, Chouinard introduced fruitful innovations. One was a residency for young choreographers at the Arsenale, the former naval yard transformed into beautiful theatres where most dance shows were held. Another welcome innovation offered short outdoor performances in a tiny park, interactivity encouraged.

Now for a roundup of the other Montrealers presented, starting with Benoît Lachambre’s ultra-interactive Lifeguard (2017). Spectators entered a large studio where Lachambre invited them, in English — the predominant language on Biennale dance stages — to walk randomly, a lesson in spatial awareness. To a strong musical beat, he inserted the handle of a broom down his shirt, swaying the brush above his head. Spectators swayed along. One woman improvised a duet. Lachambre got everyone moving, some more willingly than others. Fun with a free spirit.

Daina Ashbee’s solo, When the ice melts, will we drink the water? (2016), had Esther Gaudette smacking the stage with her back, then lying still or slightly moving and finally, in total darkness, crying, seemingly in pain. Ashbee, who is part Cree, sought empathy for Canada’s Indigenous peoples, but the work left spectators baffled.

Ashbee’s second piece, Unrelated (2014), featured Paige Culley and Areli Moran depicting the ill treatment of Canada’s Indigenous women and children. Their nudity suggested vulnerability. Both violently struck the back wall, indicating inflicted cruelty. In a conciliatory move, Culley offered a shawl to audience members, a gesture possibly relating to Indigenous traditions. More references would be welcome because Ashbee’s abstract minimalism strained people’s attention. Unrelated’s super-slow finale intensified audience impatience.

Grimness permeated Untied Tales (2015) by Clara Furey and Peter Jasko. A study in couple dynamics, the work had her licking his boot, and featured many glum looks and sad-eyed separations. One lighter moment occurred when she carried him. But Furey, usually charismatic, could not carry this gloomy show.

Superwoman Louise Lecavalier could probably carry busses. Her 2012 duet with Frédéric Tavernini, So Blue, richly showed her ability to transform gestures into suggestive emotional states.

Among European offerings, France-based Alessandro Sciarroni evoked a softer whirling dervish in Chroma (2017), 45 minutes of smiling meditation. Belgian Ann Van den Broek’s The Black Piece (2014) challenged audience’s senses by being performed in virtual total darkness where footsteps, laughter and crying evoked frightful sensations.

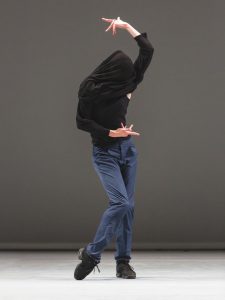

João dos Santos Martins performed Xavier Le Roy’s 1998 solo, Self Unfinished, with élan, twisting his nude body into shapes resembling insects and animals, suggesting the power of willful transformation.

France’s Mathilde Monnier and Spain’s La Ribot performed Gustavia (2013), ridiculing feminine clichés with stylish panache.

Laughter, pain, boredom, delight, energy, puzzlement — Chouinard’s Biennale program pretty much reflected dance today.

— VICTOR SWOBODA

DI FALL 2017

Photo: Nicolas Ruel