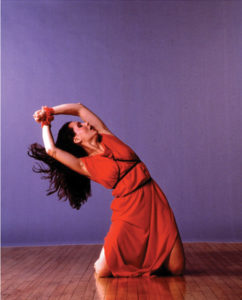

Isadora Duncan’s Marche Slav: Kathleen Hiley tackles an iconic modern dance solo

- Home

- Features 2015 - 2019

- Isadora Duncan’s Marche Slav: Kathleen Hiley tackles an iconic modern dance solo

by Holly Harris

Out of the crucible of the Russian Revolution sprang sweeping political change, social upheaval and rebellion — and Isadora Duncan’s Marche Slav. The iconic solo, which marks its centenary this year, was first performed by Duncan to celebrate Nicholas II’s abdication in 1917, an act that ultimately led to the rise of the Soviet Union.

The 12-minute work, described by Duncan in her autobiography, My Life, as portraying a “downtrodden serf under the lash of the whip” who throws off the bonds of tyranny, is fueled further by Tchaikovsky’s Marche Slav, which adds its own brooding ethos with overtones of God Save the Tsar, the national anthem of the Russian Empire.

“It is so brutally raw. I would call it primordial,” says renowned Duncan scholar and solo dance artist Jeanne Bresciani. Bresciani has served as artistic director and director of education for the New York City-based Isadora Duncan International Institute since 1987. As the main protégée of Maria-Theresa Duncan, the last of Isadora’s six adopted daughters known as the Isadorables, Bresciani learned the work directly from her. German-born Maria-Theresa, who co-founded the Duncan Institute in 1977, performed well into her 80s before her death, at age 92, in 1987.

“Every Duncan dance has that animal, human and divine level, and, I would add, the mineral and inanimate, too,” Bresciani says. “You have to be a composite being of all of those elements in order to attempt to encapsulate this work.”

Photo: Arnold Genthe

Like Marche Slav, La Marseillaise is one of Duncan’s explicitly political, allegorical

dances.

Throughout its history, only a handful of artists have been granted permission by the institute to perform Marche Slav. Its latest proponent — the only Canadian to date — is Winnipeg-based contemporary dancer Kathleen Hiley, who has been nurturing a solo career in recent years. Hiley is the artistic director of Kathleen Hiley Solo Projects; Marche Slav was presented as part of her company’s second show, performed at the Gas Station Arts Centre in November 2017.

“Being able to perform this great work of art created by the revolutionary Isadora Duncan has been a dream come true,” says Hiley of this rare opportunity to learn the solo and get it into her own blood and bones. “Isadora’s choreography is steeped in imagery, gesture and pure emotion, which is harder to express because we don’t always live in one emotion. So if it’s fear, it’s pure fear, not anxiety. If I’m expressing love, then it’s pure love. Her work is very human, and I try to tap into that as well as draw on my own experiences in life. There’s nothing mechanical about it, and I’ve learned how to not go into my dancer training, but simply bring myself to the work as honestly as I know how.”

Hiley first met Bresciani during the latter’s workshop, the Isadora Experience, held during the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s 2015 exhibition, Olympus: The Greco-Roman Collections of Berlin. Bresciani knew immediately she had discovered a dancer with a similar sensibility, subsequently inviting the younger artist to her Tempio di Danza studio located 150 kilometres north of New York City to begin their collaborative process in June 2016.

In addition to Marche Slav, Hiley began learning Duncan’s complete set of solos to Chopin’s 24 Preludes; she performed seven of them during her November show in Winnipeg, accompanied live by classical pianist Alexander Tselyakov.

Hiley also accompanied Bresciani to Delphi, Greece, last May for the newly reinstated Festival of the Delphic Games; the historic games’ first reincarnation was launched by Duncan in 1927. Hiley presented Duncan’s Prelude in D flat major, known as Raindrop, at a mini-amphitheatre situated on the archeological grounds of Mount Parnassus. She has been invited to perform Marche Slav during the 2021 Greek festival.

“There’s never been anyone that I would have wanted to remount Marche Slav on, until Kathleen. She has this wonderful combination of being mature enough, and also strong enough, with a real understanding for this work,” Bresciani enthuses. “In Duncan’s works, if you see an elbow, it’s wrong. If you see a straight line, it’s wrong … Every movement has to come from the solar plexus. Also, Kathleen has a true sense of theatre and a grasp of emotional content that one doesn’t see so often.”

Created during the third and final “Heroic” period (1913-1927) of Duncan’s career, Marche Slav is considered the first of her explicitly political, allegorical dances; others include

La Marseillaise, Pathetique and Polonaise Militaire. Each is characterized by greater angular movement vocabulary with a stronger emphasis on the downbeat, in contrast to earlier dances from her “Lyrical” (1877-1903) or even “Dramatic” (1903-1913) periods. Marche Slav boasts an impressive pedigree, with its official premiere at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House in 1917, preceded by an earlier staging as a work-in-progress in 1909.

Duncan originally created the solo while haunted by memories of Russia’s 1905 Bloody Sunday, a key event that led to the 1917 Revolution, writing in My Life that the solo, which “has been fermenting inside me for a long time … burst out of me.” That first incarnation featured a similar musical interpretation, yet different physical expression of its choreography, according to Bresciani.

Photo: Lois Greenfield

“Marche Slav differed tremendously as it went from a war cry of encouragement at the U.S. entry into the First World War to its presentations in Russia, which was even more stark in the first third of the dance … in order not to incite the Bolsheviks with the Czarist hymn,” she states of its deepening evolution.

Reviewing Bresciani’s 2006 performance at the Art of the Solo mixed bill in Baltimore, American dance critic George Jackson wrote in Dance View Times: “In Isadora Duncan’s Marche Slav, subtlety wasn’t the point. Power was! Jeanne Bresciani was a figure larger than life. Weight seemed a burden, tension threatened to tear this body apart, resistance became a revolution and liberation from bondage the ultimate transfiguration. Bresciani, moving like tubular Picasso women must if set free in time, brought ‘The Art of the Solo’ to a rousing close.”

Marche Slav’s sole male interpreter remains Jamaican-born dancer Clive Thompson, who also performed with the Martha Graham Dance Company and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Thompson presented the work during the memorial service for Maria-Theresa, from whom he learnt it, at Lincoln Center in 1988.

“Being Jamaican, Clive had an innate understanding of the tradition of being persecuted, although he was a creature of light and love and happiness,” Bresciani recalls of his portrayal of the physically demanding work, in which the “serf” ultimately casts off heavy red ropes of oppression and creates visceral full-body whip cracks. “The amazing thing about Duncan is that her dances can be done in so many different ways, including by different ages and body types, and can still have a similar power and range.”

The New York Times’ Jack Anderson agreed: “Portraying a slave who breaks the bonds of oppression, Mr. Thompson demonstrated that this solo concerns a desire for freedom that can be shared by men and women alike.”

Therein lies one of the great ironies of Duncan, whose artistry is defined by opposing forces. Even her bold social protests inspired by the fiery spirit of revolution are simultaneously driven by profound messages of universal peace.

“Isadora Duncan is a divine, paradoxical person. Her very nature was terribly contradictory,” Bresciani says. “She was not a person of dogma, but a person of faith. Not an academic, although she was a part of the intelligentsia, but self-educated as an otherworldly citizen of the world. Also, Isadora was a much larger figure than just one political cause. It was never for a specific group except in the moment, and then it would be transferred to the next and the next after that.”

Is there any joy in this solo? “There is, and that’s the beauty of it,” she says. “No matter what Isadora has gone through, there’s never the loss of soul in her dances. As with all her works, Marche Slav is ultimately about the triumph of the human spirit.”

As its latest interpreter, Kathleen Hiley is deeply appreciative of the opportunity to become a vessel for one of the “Mother of Modern Dance’s” revolutionary works that shook the world.

DI WINTER 2017

Photo: Mark Dela Cruz