L.A. Dance Project: Peck, Graham, Millepied / Mixed Bill

- Home

- Reviews 2014 - 2019

- L.A. Dance Project: Peck, Graham, Millepied / Mixed Bill

Excitement filled the big tent at the Festival des arts de Saint-Sauveur for the Quebec premiere of L.A. Dance Project on August 2. As the festival’s executive director Étienne Lavigne told the crowd in his opening remarks, “This is the ‘It’ company of the moment.”

Founded in 2012, the company has an undeniable “certain something,” particularly with charismatic dancer, choreographer and filmmaker Benjamin Millepied at its helm. By all accounts, choreographers, designers, composers and dancers are flocking to the former New York City Ballet principal dancer’s well-funded venture in the motion picture capital. Local dance companies haven’t flourished in Los Angeles, but, over the last five years, L.A. Dance Project has apparently been drawing a young audience hungry for culture.

The evening opener was Murder Ballades, by one of the great new hopes of American dance, Justin Peck, a former NYCB dancing colleague of Millepied’s. American composer Bryce Dessner took instrumental murder ballads from the 1930s and 1940s, adapting the distinctive tunes (without the lyrics) for a chamber group called Eighth Blackbird. There’s a bright optimistic sound and look to the piece that is very American, in the best sense, in terms of energy and expansive possibility.

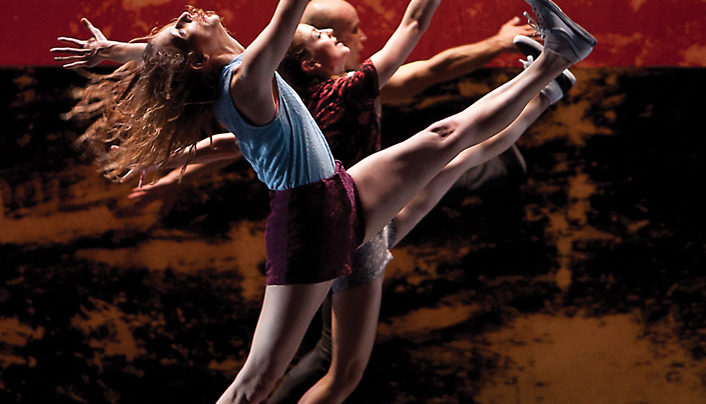

The piece, in seven sections, feels adventurous, elaborate in its construction, and Peck knows how to highlight his cast’s strengths. Peck works with line, pacing, poetic fluid movement and rounded configurations; while there’s lots of fast and frenetic activity, the solid partnering is easy to appreciate. Watching the six dancers, dressed in T-shirts, spandex shorts and sneakers, their alert, playful sensibility gives a real sense of an ensemble. Some darker tones surface in quick sequences involving inert, prone bodies, but where’s the crime in the dance? Overall, Murder Ballades sustains itself as an energetic, pleasurable program opener, though Peck’s reliance on blackouts to move the work forward cuts the cohesion in the piece.

Photo: Rose Eichenbaum

Right afterward, I overheard the fellow sitting next to me say, “Jerome Robbins is alive and well.” That man is on to something. The key in dancing his work was to express joy in being yourself, and many of his works register because of that clarity, but Robbins’ dancers also hold back a just a bit and draw audiences in. So do Peck’s dancers.

Next was a series of short duets by modern dance giant Martha Graham, followed by two of Millepied’s own creations. That range is certainly one way to start conversations about dance.

Graham’s dances (without sets), lasting all of eight minutes, anchored the evening. The first, White Duet, performed by Rachelle Rafailedes and Nathan Makolandra, was inspired by the duet from Diversion of Angels (1948), and is a light, lyrical work about maturing young love. The second and third duets, titled Star and Moon (with Stephanie Amurao and Aaron Carr, and Julia Eichten and Robbie Moore, respectively), are from Canticle for Innocent Comedians (1952), Graham’s ode to the cycle of life and the elements.

In these lesser-known duets, the dancers — in loose black T-shirts for the men, and white loose top and shorts for the women, designed for L.A. Dance Project by company dancer (and former NYCB principal) Janie Taylor — perform with a sense of exaltation in Star and a serene wonderment in Moon. Removed from their original context, it’s difficult to understand Graham’s intentions, but there’s plenty to imagine. None of the severe, wrenching force or the weighted lunges associated with her archetypal work are on view. Nor do the dancers appear to be steeped in the famous technique, but that’s not a slight, per se; there’s clarity in their bodies, and it’s easy to see how these well-structured pieces, set to arrangements of Cameron McCosh’s music, are relevant in the present.

Millepied, a protégé of Robbins, develops group dynamics in his own two works. In Silence We Speak (2017) was a 15-minute duet performed by Rafailedes and Taylor, both with long, blond hair. The piece is quiet and enigmatic, with slow, unfolding movement, and captivating music by David Lang. There are suggestions of intimacy, where one reins in the other, but more often the work is detached, and the suggestion of acceptance at the end unconvincing.

Hearts & Arrows (2014), set to Philip Glass, is the second part of a trilogy, Gems (perhaps a nod to NYCB’s Balanchine three-act Jewels). As a dancer in many Balanchine ballets, Millepied knows something about Mr. B’s work, and he’s picked up on the master’s sophisticated approach to partnering, the attention to lightness of feet, transitions from one foot to the other, the way the woman is held and a delicate off-balance approach.

Hearts & Arrows relies on intricate, interlacing group patterns, and again the dancers (once more in sneakers) move beautifully, but little is memorable in the choreography. It all felt random, and the blackouts don’t help. The score’s complexity and control, with its emotional richness, is simply not echoed in Millepied’s dance.

L.A. Dance Project features 10 superlative dancers, gorgeously trained and solidly rehearsed, with a deep understanding of rhythm, musicality and attack. If only the choreography would deliver.

— PHILIP SZPORER

DI WINTER 2017

Tags: Benjamin Millepied Etienne Lavigne George Balanchine international dance news Janie Taylor Justin Peck L.A. Dance Project Martha Graham modern and contemporary dance Rachelle Rafailedes