Winnipeg: Spring 2018

- Home

- City Reports 2015 - 2019

- Winnipeg: Spring 2018

by Holly Harris

The Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s artistic director André Lewis took audiences down memory lane with the program Our Story, featuring seminal turning points in the company’s 78-year history. The historically rich mixed bill, also celebrating Canada 150, paid homage to six prominent choreographers who have left their footprint on the “Prairie fresh” company, including a premiere by one of them, Peter Quanz (who is also an alum of the RWB School Professional Division).

By its very nature, Our Story also honoured the company’s late legendary artistic director Arnold Spohr, whose diverse programming would regularly include a classical piece, a dramatic work and “something to wake up the husbands.”

The three shows held mid-November 2017 and, unusually, performed with recorded music, were staged not in the company’s typical stomping grounds of the Centennial Concert Hall, but in its in-house performance space, the RWB Founders Studio. While infusing the two-hour evening with greater intimacy, the location suggests ever-looming fiscal restraint biting at the heels of so many arts organizations today.

The mixed bill opened with Quanz’s classically inspired ballet straight against the light I cross, performed on pointe. It’s his first commissioned work created for the RWB, though the company has performed other Quanz ballets, co-produced with his own company Q Dance — and dedicated to the late Les Grands Ballets Canadiens de Montréal dance artist Vincent Warren (see Obituaries on page 29), a revered mentor.

Performed by a 12-dancer ensemble to Canadian composer Marjan Mozetich’s Concerto for bassoon and string orchestra with marimba, and featuring Anne Armit’s sleek blue-grey unitards, the 21-minute piece, titled after American Frank O’Hara’s poetry, suggested chapters in the choreographer’s own artistic story, evoking the sweeping lyricism of his 2010 signature work Luminous, the sculptural liquidity of his 2011 full-length ballet Rodin /Claudel, the sparkling ebullience of his 2014 pas de deux Blushing, and the emotional, plumbed depths of 2013’s Untitled.

In straight against the light I cross, Quanz bleeds smaller ensembles into a larger whole, with the dancers appearing like constantly shifting sands of kinetic movement that felt somewhat hectic at times. Longtime RWB soloist Yosuke Mino with soloist Alanna McAdie burst into playful skips during their pas de deux, while second soloists Liam Caines and Elizabeth Lamont’s more introspective section includes Lamont being lifted with her flexed feet undulating in the air like sheaves of blowing wheat. Corps de ballet members Saeka Shirai and Yue Shi performed intricate steps comprised of abrupt shifts of direction, juxtaposed with soaring lifts.

Photo: Simeon Rusnak

Quanz’s final barren landscape features the male dancers curling their bodies around the women’s feet — literally grounding the ballet and each other — before everyone rises again to leave the stage except for Caines and Lamont. When Lamont also departs into a shaft of light, Caines remains lying on the floor, utterly alone, human and vulnerable, as one might feel after losing a friend and steadfast advisor.

Another cornerstone of the evening was Miroirs, by the company’s first resident choreographer and former soloist, Mark Godden, commissioned by the RWB in 1995 and set to Ravel’s impressionistic solo piano suite of the same name. The beautifully crafted contemporary ballet unfolding in five movements is steeped in Godden’s darkly dramatic aesthetic and architectural sensibility.

Standout performances include principal dancers Jo-Ann Sundermeier and Dmitri Dovgoselets in the first section, Bird, with their pensive movement arriving at moments of stillness, including its final image of Sundermeier clasping her fists to her face.

Mino popped like a champagne cork during his effervescent Jester solo, bounding about the stage with a white feather quill and furled scroll, a testament to this powerhouse dancer’s still enthralling athleticism at an age when others are honing their stable of character roles. In Boats, Sophia Lee, Yayoi Ban, Caines and Tyler Carver created elegantly lyrical lines heightened further with Paul Daigle’s long, flowing skirts. The final movement, Bell, includes a trompe d’oeil in which McAdie wildly swings between Josh Reynolds’ and Stephan Azulay’s taut arms like a joyous, pealing bell.

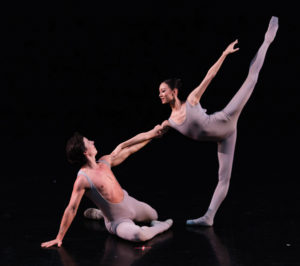

The program also included a rare performance of Norbert Vesak’s Belong pas de deux from his RWB-commissioned 1973 ballet What to Do Till the Messiah Comes. Dovgoselets and Chenxin Liu were given the daunting task of interpreting the searing work that had earned the RWB’s former prima ballerina assoluta Evelyn Hart a prestigious gold medal with David Peregrine at the Varna International Ballet Competition in 1980, and became one of her signature works.

Dovgoselets and Liu executed the near-mythical duet, which features an electro-acoustic score by Syrinx, with fluid, expressive grace and athletic strength, their bodies entwining like lovers’ limbs. A greater emotional connection between the two dancers would have deepened their performance even further.

The program also included LED, choreographed by Shawn Hounsell (a former RWB dancer) in honour of principal Tara Birtwhistle’s retirement from the stage in 2008, when she performed the duet with husband Dovgoselets. Another real-life power couple, Sundermeier and Reynolds brought the requisite intensity to the stirring work set to Arvo Pärt’s Für Alina, performing Hounsell’s often gestural, angular choreography, punctuated by recorded, organic breath sounds, with controlled precision.

The evening’s oldest offering featured another company pillar, the internationally renowned choreographer and director Brian Macdonald, represented by his tongue-in-cheek story ballet Pas D’Action. The late dance artist’s wife, retired ballerina Annette av Paul, travelled from her Stratford, Ontario, home to stage the work. Av Paul, who was in the audience on opening night, had premiered the work with another RWB icon, David Moroni, a former principal dancer and the founder of the RWB School’s Professional Division.

Macdonald’s fantastical kingdom featuring Lamont’s Princess Naissa and her co-conspirators — Carver’s Prince Sebastian, Shi’s Count Florimund, Ryan Vetter’s Duke of Westphalia and Caines’ Telemund — perform goofy leaps, spin like tops before collapsing into the floor and gasp for air during lifts, making the difficult choreography look oh-so-easy. Kudos to Lamont for her comic acting skills, not to mention pristine technique, with her final solo capped by a blaze of flashing fouettés.

Finally, the evening featured Jacques Lemay’s Le Jazz Hot, premiered in 1985 by the acclaimed choreographer, who performed it then with RWB principal dancer Laura Graham (who came to mount the work). The duet featured Lee and Azulay, outfitted in Lemay’s own costume design of bowler hats, character shoes, fringed dress (for her), and natty vest, trousers and bow tie (for him). The tour-de-force work melds jazz dance with balletic technique, with these two dancers high kicking, shaking and shimmying to a sizzling Henry Mancini score, perhaps pushed out of their comfort zones, but clearly having the time of their lives.

As Canada’s oldest ballet company, and notably North America’s longest continuously operating troupe, the Royal Winnipeg Ballet has proven many times over its resilience and fortitude, able to constantly reinvent itself, and moving now toward its 80th anniversary in the 2019-2020 season.

Photo: Simeon Rusnak