Creating Relationships: Choreographer Helen Pickett Builds Bonds Onstage and Off

- Home

- Features 2015 - 2019

- Creating Relationships: Choreographer Helen Pickett Builds Bonds Onstage and Off

by Cynthia Bond Perry

To find a way into Helen Pickett’s creative existence, and the many worlds she creates, look to her characters.

In Pickett’s The Crucible — commissioned by Scottish Ballet and based on the play by Arthur Miller — Abigail Williams is a young teen traumatized by seeing her parents killed. Yearning to fit into the structure of the family where she is a servant, Abigail develops a crush on John Proctor, head of the household. Their affair is the tipping point, Pickett said, for a girl who is too young to understand the sexual encounter and, then, too emotionally fragile to recover from the ensuing rejection. With the role of Abigail, Pickett digs deep to unearth the layers of a character who will feed hysteria within her community to devastating effect.

Photo: Andy Ross

Set to premiere at the 2019 Edinburgh International Festival, The Crucible is the centrepiece of Scottish Ballet’s 50th anniversary season. When we met in the lobby of New York’s Joyce Theater last spring, Pickett was in the thick of creation, in between trips to Glasgow, Tulsa, San Francisco, Oklahoma City and Charlotte, North Carolina, where five of her ballets were in various stages of planning, rehearsal and production.

Pickett is a contemporary ballet choreographer of substance, with deep convictions, an effervescent sense of humour and a wide-ranging intellect. She is also one of few women working in the ballet world’s higher levels, and one of fewer still who are tackling full-length narrative ballets of serious dramatic heft.

Pickett spent 11 years with William Forsythe’s Frankfurt Ballet and shares his respect for classical ballet, love of collaboration and commitment to discovering new modes of creation. Since leaving the company in 1998, however, she has accrued about 20 years of further experience to distinguish her voice as a choreographer.

“I have a movement style from my heritage. But it always needs to evolve,” Pickett says. “The human component — each new company — shapes every piece.”

In each company Pickett enters, she forges intimate connections with dancers. Through these relationships, she gets to the essence of her characters, whose multifaceted personalities are like windows into her creative worlds.

Photo: Tatiana Wills

Sarah Hillmer, Pickett’s choreographic assistant, has worked with her for eight years. “Helen cares deeply about people. I think she’s really drawn to a human story,” Hillmer says. If there’s a through line in Pickett’s career, she adds, it’s the need to understand the “why” of her characters’ behaviour.

Such curiosity runs in Pickett’s family. Her parents worked as actors in New York during the 1960s before settling in San Diego shortly before their daughter’s birth. As a child, Pickett put on her own plays at home, her parents and grandfather comprising the cast. Her ballet ambitions started at age eight when she saw The Nutcracker. Disappointed that the ballerinas didn’t stay up on pointe the entire time, Pickett resolved to become the first to do so.

As a scholarship student at San Francisco Ballet School during the mid-1980s, Pickett wore her pointe shoes extra wide so she could work her feet more against the floor. For Pickett, the pointe shoe was not a restriction — it was, and remains, a means to greater freedom and possibility. “It was the precarious nature of the shoe that I loved,” she says.

Pickett first encountered Forsythe when she was a student in San Francisco, and would watch from the studio doorway while he was creating New Sleep with the company. Forsythe’s method of inviting dancers to bring their voices to the creative process, and discovering new movement ideas together, aligned with Pickett’s yearning for independence and tendency to question authority and rules of engagement in the classical ballet world.

“I’d never seen a person work like this with dancers,” Pickett says. “Laughter. Asking people’s opinions, getting in the mosh-pit.”

Within a year, Pickett had joined Frankfurt Ballet and performed in one of New Sleep’s leading duets during her first season there.

Pickett learned her craft through Forsythe’s collaborative process. Forsythe would choreograph several phrases, each up to five minutes long. He’d then ask dancers to “cut and splice, deconstruct, create new solos, new duets, new quartets, new trios out of it,” Pickett says. “It was on-the-job training.”

After a dislocated knee signalled her retirement from Forsythe’s company, Pickett entered a period where, she says, “I kept stepping into different métiers of creativity.” She joined the Wooster Group, a New York-based experimental theatre company, at age 31. With the group’s director, Elizabeth LeCompte, Pickett participated in multilayered theatre works, built from the ground up. She also studied method acting, learning new tactics for accessing a character by diving into her own psyche to understand the layers of a character’s personality.

Work with video artist Eve Sussman in the early 2000s allowed Pickett to experience many aspects of filmmaking. Through the stillness inherent in film, Pickett says she learned about the intensity and psychology of a character’s internal life. She also studied somatics with Irene Dowd during this time. The combined influences of theatre, film and somatics would later give her tools to heighten emotions and sensations in her ballets.

Pickett was teaching a workshop in Forsythe’s improvisation technologies at Boston Ballet’s studios when she invited company artistic director Mikko Nissinen to observe. Nissinen was seeking new choreographic voices, and, he said, Pickett’s background in classical ballet, Forsythe’s contemporary approach and theatre made her “well-positioned” to be a successful dancemaker. He commissioned a work, and the company premiered Pickett’s Etesian in 2005.

Named after Aegean summer winds, Etesian was a study of touch in partnering. Dancers often lose sensitivity to touch, Pickett says, because rehearsing requires frequent physical contact. With Etesian, Pickett helped dancers tune into the energy of their partner when touching them. This opened channels of communication that electrified their performances.

Boston Ballet nominated Pickett for a 2006 New York Choreographic Institute Fellowship Initiative Grant, which she received to create a 10-minute work-in-progress for a Boston Ballet studio showing. Within two years, Pickett had expanded it into a one-act ballet for Aspen/Santa Fe Ballet. Titled Petal, the work “was about spring and the vibrancy of Gerber daisies and also the delicacy and the strength of this little, velvety piece of living nature,” Pickett says.

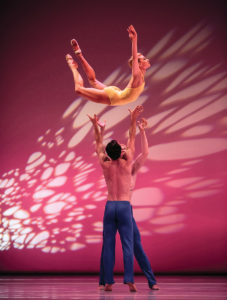

Photo: Chris Hardy

Petal explores the nature of human connection, especially through the senses. On a stage saturated in yellow, pink and purple hues, four couples slip through shifting configurations, folding into each other and opening outward. As the music’s lilting momentum grows urgent, two men and a woman alternately push one another’s limbs away, and through a woven progression of supported arches, floor slides and overhead lifts, every detail speaks of the pulls and tensions of relationships — the urge to connect with others, the fragility of trust and the beauty of nature when freed to exist in its fullness and glory.

Petal’s sensory rush of colour and lyricism has helped to make the work Pickett’s most popular ballet. Directors often ask why she doesn’t make more ballets like it. “It’s not that Petal’s not a good piece — I stand by that piece,” Pickett says. “I just don’t want to be defined by a formula.”

Over the years, Pickett has developed new approaches to directing dancers, drawn largely from research conducted while earning a master of fine arts in dance from Hollins University in Virginia. She pursued interests in crossing the theatre’s fourth wall via the senses, especially proprioception and tactility in movement. Pickett’s research gave her new language to communicate with dancers when she staged Petal on Atlanta Ballet in 2011.

On opening night, viewers were palpably engaged from the start, when dancer Nadia Mara stretched her body through lemniscate (figure-eight) patterns. Company artistic director John McFall then commissioned Pickett to create Prayer of Touch, which led to her appointment as resident choreographer for what would become a five-year term.

Pickett’s collaborative approach fit well with Atlanta Ballet, where McFall created an open environment, nurturing dancers to contribute ideas and opinions to the dance-making process. “The dancers and I got to a point where we could

finish each other’s sentences, in movement,” Pickett says.

Trust and rapport provided a baseline for creative risk-taking. In The Exiled, her second Atlanta Ballet commission, Pickett dug into a dramatic scenario she’d long wanted to explore — an existential world in which three criminals are trapped behind a Plexiglas barrier while two vigilante characters called Reckoners hand down judgment on the three.

Pickett and several dancers wrote an original script together, creating a narrative that became her anchor. “It was my first foray into working with narrative, which I absolutely fell in love with.”

Picket took another leap of faith with her final work for Atlanta Ballet, her first full-length narrative ballet — an adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ Camino Real. During its 1953 Broadway premiere, the surreal play stirred the minds of poets and artists, but for the most part failed to touch down with general audiences, according to Pickett. She conveyed the essence of Williams’ message through the intertwined arcs of five characters — especially Gutman, a villain who maintains a tyrannical grip on the town, and Kilroy, the big-hearted hero. Stranded on the Camino, a kind of purgatory of lost souls, Kilroy must choose to live, silenced, under Gutman’s thumb — or die on his own terms.

Camino Real’s themes — the silencing of voices, persecution of knowledge and hatred of differences — reappear in The Crucible, Pickett’s second full-length narrative ballet. She is also working with some of the same collaborators: designers Emma Kingsbury and David Finn, who have created an austere Puritanical realm, and composer Peter Salem, who propels The Crucible’s story through an emotionally textured score.

Also like Camino Real, Pickett invited dancers in The Crucible to bring personal research and experiences to their characters. It’s a process she nearly always employs, because, she says, it brings authenticity to their performances. She wants us to recognize ourselves in the ballet’s characters, “all the foibles and, also, all of the places where we put our foot down and say no.”

In Miller’s play, the Salem witch trials are an allegory for U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anticommunist campaign of the early 1950s, but its themes are timeless and universal — intolerance, misuse of power and the choice to live without integrity or die to preserve it.

Scottish Ballet artistic director Christopher Hampson plans to tour The Crucible to major Scottish cities and, hopefully, internationally. Meanwhile, Pickett is preparing another world premiere with Charlotte Ballet, slated for April 2019, based on photographs of Stephen Shore and the formation of memory.

Whether a misguided youth like Abigail, or a down-on-his-luck hero like Kilroy, Pickett’s characters and her ballets are a way for her to continue digging, “folding in,” helping to uncover deeper questions and reveal new truths about what it means to be human.

For audiences, Pickett’s worlds are multifaceted and ever-changing. It can be disorienting to lose oneself there. Intimacy can be terrifying. But in venturing into these virtual realms, three takeaways emerge: through trust, people open up. Through connections, they explore. Through relationships, human beings struggle, learn and evolve.

Photo: Charlie McCullers