Milan: Fall 2019

- Home

- City Reports 2015 - 2019

- Milan: Fall 2019

By Silvia Poletti

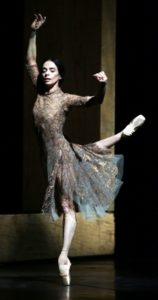

Wayne McGregor’s full-evening Woolf Works, created for the Royal Ballet in 2015, arrived last April to La Scala’s stage thanks to Alessandra Ferri, whom McGregor cast as the lead in the original production. On that occasion, Ferri returned to the stage after a leave of more than seven years and, at 52, faced a demanding new way of working and a new conception of dance storytelling. A celebrated dancer actress of iconic roles from the traditional repertoire, the Italian ballerina used her still malleable body for the whirling enchaînements and multi-directional dynamics of McGregor’s style, and also had to find new acting skills to express not simply a character but, as she explained to me during an interview, “the feelings of the character in a certain event of her life.”

Not only did Woolf Works win important critics’ awards, but since then Ferri has become McGregor’s special muse, creating the principal role in his first ballet for American Ballet Theatre, AFTERITE, and some duets.

McGregor’s creations are known by Italian dancegoers and often appreciated (his Autobiography won the Italian magazine Danza & Danza critics’ award for best contemporary work in 2018), but the Scala stage is a difficult place to conquer, above all because the ballet repertoire rarely includes contemporary dance works. Therefore, the Italian success of Woolf Works was all the more remarkable. Not only did the Scala box office do well, but the overall buzz led to a broadcast of the Royal Ballet’s edition of the ballet on the Italian Rai television arts channel.

The work is based upon three celebrated novels by Virginia Woolf — Mrs. Dalloway, Orlando, The Waves — as well as her own life and ideas about writing and the dynamics of emotions. Woolf Works is a very interesting contemporary dance-drama composition, with fundamental help from the dramaturg Uzma Hameed, in which McGregor translates the different styles of Woolf’s three novels into choreographic scores.

The opening, I Now/I Then, starts with Woolf’s recorded voice speaking about the constant dilemma of finding new forms to express the beauty of truth. The focus of the plot is a middle-aged woman, Clarissa Dalloway (Alessandra Ferri), and the memories, sensations, longings and hopes crossing her mind on a summer day in London, while she is preparing a birthday party. A melancholic mood changes quickly to light-heartedness, which turns back to sobriety while the plot goes backward and forward through time and other characters enter: her first love Peter, her opaque husband, herself as a witty teenager and Sally, the girl she once kissed.

The memories and the present situation are presented in a stream of dance with crossed trios, quartets and duets, with the present-day Clarissa fluidly interlacing her gestures and movements to the others’ dances. Ferri is truly one of a kind for the special way she has of “dancing” with her glances or a fading smile.

In presenting the characters’ inner conflicts, McGregor’s choreography stays close to the contemporary dramatic ballet mainstream, but at the same time remains original in the theatrical vision of his piece. This is especially so in the third act, titled Tuesday, inspired not only by The Waves, but also by the last letter Woolf wrote to her husband before committing suicide in the River Ouse. Ferri is the dramatic focus as, tiny and frail, she shows us the despair and sorrow of her last moments. On a screen, grey waves give the timing of the dance: the dancers, like those moving waters, sweetly and calmly repeat the same rhythm, and carefully embrace the woman who is letting herself go.

In the middle section, Becomings, the Orlando plot is based upon the story of an Elizabethan poet who over the centuries changes gender. The idea of transformation is the starting point of the most McGregorian of the three parts of Woolf Works, featuring his typical qualities of speed, hyperextensions, flexible torsions of the torso, and twirling and curling dynamics.

The Scala dancers were the surprise of the show. Not as accustomed to contemporary choreography as other ballet companies around the world, they danced with panache and passion. All the best were in the cast: the three lively principals Nicoletta Manni, Martina Arduino and Virna Toppi; Timofej Andrijashenko and Claudio Coviello in the moving Septimius duet; the soloist Christian Fagetti sparkling in the Becoming act.

A friend of Ferri’s from the Royal Ballet, another Italian, Federico Bonelli, came to perform (he was in two acts of Woolf Works) and was warmly greeted for his virile, careful presence.

For a while, La Scala breathed a contemporary air of what ballet of our time can really be, with laser lights by Lucy Carter and an elegiac score by Max Richter. “They needed it,” Ferri said, clearly satisfied to have brought Woolf Works to her former theatre.

Photo: Brescia e Amisano, courtesy of La Scala Ballet