Gärtnerplatztheater Ballet: Eyal Dadon / Salome Tanz

- Home

- Reviews 2020 - 2023

- Gärtnerplatztheater Ballet: Eyal Dadon / Salome Tanz

The premiere in February of Eyal Dadon’s Salome Tanz (Salome Dance) with Munich’s Gärtnerplatztheater Ballet was anticipated with great excitement. Up until opening night, on a special website, the audience was invited to vote for the following peculiar pairings: black/red, chamber/cage, moon/sun, mayonnaise/ketchup. Whichever got the majority vote would be incorporated into the production.

Dadon is a 31-year-old choreographer from Israel, artistic director of the House of Dance in Be’er Sheva and founder of SOL Dance company. His new piece is inspired by Oscar Wilde’s play Salome, about the daughter of Herodias. Salome’s stepfather, Herod, is so infatuated with her that he promises her half his kingdom if she dances for him. She does, demanding as her reward the head of Jokanaan, the Prophet, who has rejected her advances.

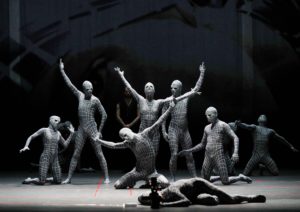

Wilde’s play is about lust, passion and power, but Dadon does not focus on these elements. Instead, as stated in an interview, he sees strong-willed and stubborn Salome as a virus destroying a well-functioning system, which, he adds, is similar to how many politicians are behaving at the moment. To realize this vision, Dadon does not use the dramatic form, but stages an interactive video game in five levels. There are no individual characters, only two groups: cyborgs in body suits which make the dancers look as if they are made out of wire, and women and men uniformly clad in dark baggy pants and long vests. Costumes are by Bregje van Balen, and the action takes place in a nondescript chamber designed by Matthias Koch. That chamber is one result of the pre-performance voting.

Salome Tanz begins with a video showing a close-up of the head of a man, perhaps the Prophet. Behind him on a backdrop are projected text snippets such as: “Have you seen her?” and “I feel I could lose my head over her.” The man’s neck is revealed, covered in a red mush in which he dips French fries. Thus, the ketchup (not the mayonnaise) from the pre-performance voting. Videos and live projections, by Christian Gasteiger and Thomas Mahnecke, are a crucial part of the performance, often showing close-ups of the onstage action.

Each level of the game has a title remotely connected to Wilde’s play, but the dance movement itself is made up mostly of a series of senseless killings. There are no protagonists. The identically clad dancers seem to take turns in the roles of leaders or victims throughout, making it hard to keep track of who is dancing what. The game starts with one of the men (Joel Di Stefano) running on the spot toward a single file or groups of cyborgs, whom he shoots, using his hand to mime a gun. Instead of dissolving as they would on a screen, the cyborgs run offstage, just to appear again.

Level 2, Dance for me, is a series of solos; in level 3, Give me the head, some dancers wear masks which make their heads look like long bloody necks from which strings of cartilage or veins swing. The climax comes in level 4, where a woman with an outstretched arm beheads a whole line of approaching people. At one point, they all start beheading each other and themselves. Everything ends with level 6 and the text That is all. The dance/game is over.

The music was a mix from different eras and styles, by classical composer Franz Schreker and Franz Schubert, the experimentalist John Cage and contemporary composer Caroline Shaw, played with great empathy by the Gärtnerplatztheater Orchestre conducted by Michael Brandstätter. The discrepancy between the violent action and the music, which mostly sounded like a romantic film score, made the atrocities onstage surprisingly palatable.

I am not a fan of violent video games, but found, to my surprise, that I enjoyed the actual performance. The 20 dancers, throughout, mastered Dadon’s fast, sinuous and quirky style extremely well, and the audience participation was fun. Besides the pre-show voting, at the start of the evening audience members were handed out a card with a black circle on one side and a white cross on the other, with instruction to use it to vote during the performance on such questions as, “Will you help me?” and “Who shall die, him or her?”

After the show was over, though, I had my qualms over the evening. Had Dadon not made it clear by the title and program note what the work was based on, I would never have guessed it. Also, by eliminating the protagonists, Dadon eliminated the drama. Salome Tanz became a collective massacre happening for no apparent reason and for which nobody could be held responsible. The violence just seemed to take place and when it was over, it was of no importance to anybody.

— JEANNETTE ANDERSEN