Iván Vargas: How a flamenco artist from the zambras is surviving quarantine

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Iván Vargas: How a flamenco artist from the zambras is surviving quarantine

By Bridgit Luján

Few gypsies still live in Granada’s Sacromonte caves, but the performing venues known as zambras continue to flourish. “Zambra” references a song and dance party that dates back to the 16th-century nuptial rituals of the Moors; last year, the city of Granada initiated procedures with UNESCO to declare the zambras of Sacromonte an Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

A younger generation of artists, such as 34-year-old Iván Vargas, who hails from La Cueva de la Rocío (The Cave of the Dew), are keeping the unique style of Granada’s flamenco alive while also pushing the art form forward through performing and teaching not only in the Sacromonte, but also internationally.

Vargas belongs to a dynasty of great dancers, Los Mayas, that includes Mario Maya, an icon in flamenco dance. Maya’s daughter Belén shared the story of how Granada became his home soon after he was born in Cordoba. “Mario’s father wanted nothing to do with his newborn son, so, to start a new life, his mother Trinidad walked from Cordoba to Granada carrying Mario as an infant in her arms.” This 100-mile journey on foot brought Maya to the caves of Sacromonte, where he would develop the skills that provided the foundation for his personal dance style and philosophy that revolutionized modern flamenco.

In 2002, Maya established the Centro Flamenco de Estudios Escénicos Mario Maya, located in the heart of Granada’s gypsy quarter, in a building known as La Chumbera (The Prickly Pear). This is where Vargas studied for a time, and where he now teaches.

Today, the school is called Escuela Internacional de Flamenco Manolete — named after the flamenco artist, another iconic name, who took it over after Maya died in 2008. Manolete changed the focus from professional studies in choreography and stage direction, to training for flamenco students of all ages and abilities.

Vargas teaches youth, intermediate and advanced level classes. A few months ago one of his students, 10-year-old Triana la Canela, competed in Spain’s popular television show Got Talent España, making it to the final round. During the lockdown, he has been sharing bits of choreography with his international students on Facebook, who have flooded his page with videos of themselves conquering the steps.

Performances at La Cueva de la Rocío began in 1951. In Vargas’ childhood, the cave was closed for a period of mourning after the passing of his great-grandmother, but re-opened in 1996. At age 11, Vargas began dancing there under the direction of his grandmother Salvadora. First cousin to Mario Maya and Manolete, Salvadora today still lives at La Cueva de la Rocío. Below her home, where the family often gathers, there are two lower caves where performances happen simultaneously, allowing for up to six performances nightly; a third cave is a restaurant. Artistic direction of the performances was passed down in 2008 to Salvadora’s son, Juan Andrés Maya, Vargas’ uncle.

When Vargas talks about La Cueva de la Rocío, he does not call it a zambra but rather the cueva (cave). He explains: “Our show still includes a section that celebrates the traditional gypsy wedding, with dances such as Fandangos de Albaycín and alborea, but we also offer contemporary flamenco styles that are seen all over Spain such as alegrías and solea por bulerías. The term zambra references a very specific set of traditional folkloric flamenco dances and today the cave performances offer much more, so we [refer to] the cave rather than to the zambra to reflect that progression.”

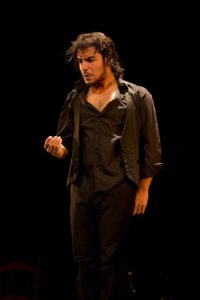

Vargas is an explosive dancer who has appeared in international festivals such the Festival de Jerez, the Malaga Biennial, the Contemporary Iberian Festival in Mexico and the Festival Flamenco International de Albuquerque. He embodies the illusive contradiction in male flamenco dance of masculinity and beauty, strength and tenderness, evident in his own 2013 show, Yo Mismo (Myself), which he has taken to Japan, Brazil, Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, France, the United States, etc.

In Yo Mismo, he pays homage to his gypsy ancestors with dances set to the early a cappella gypsy work songs of trilla and martinete, which grew from the natural rhythm of threshing and blacksmithing respectively. He also performs Manolete’s famed farruca, a classic choreography, and presents his own energetic choreography of alegrías. At the end, he closes with a rapid sequence of a jump, turn and backbend, his signature closing to bulerías.

Yo Mismo also includes a taranto, a dance from the mines, which Vargas said he selected because “taranto is a good fit for my temperament, I relate strongly to it, and of course it ends in tangos.” Tangos is a fundamental native style of the zambra, evolving from Moorish tangos to tangos de graná (short for Granada). Tangos is considered one of the most difficult rhythms for male dancers to embody; however, Vargas manifests with ease the soul of this powerful, earthy and sensuous style rooted in his heritage.

For Vargas, flamenco is a way of life; it is his work, hobby, study and entertainment. The lockdown has not changed that and he is passing the time with a little study, watching videos of dancers who inspire him, such as Eva la Yerbabuena, Manuel Liñan and his uncle Juan Andrés Maya. He lives in the upper Albaycín neighbourhood with his younger sister, Rocío, also a dancer, with whom he continues to share his art during the lockdown. Nearby are his parents, his aunt and uncle, and many cousins.

“The stay-at-home orders do not allow us to go anywhere,” he says. “I cannot go to the cave to rehearse or even to visit my grandmother. I can’t go to La Chumbera to rehearse alone in the studio, so I have been practicing out on the terrace to avoid disturbing my neighbours.”

“Everyone in flamenco has lost all their bookings for the coming months and the government does not provide any help for flamenco artists,” says Vargas. In response, in mid-April artists across Spain came together to form Unión Flamenca, the Association of Professional Flamenco Artists, to be able to engage with the Ministry of Culture and have their voice represented.

With the confinement of the artists indoors, flamenco has returned to the private intimate space of the family where it originated, back to the introspection of resilience against crushing hardship. This time of reconnection with its ancestral roots promises a transformation for post-pandemic flamenco.