New Contexts for New Times: Julianne Chapple carves out an online presence

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- New Contexts for New Times: Julianne Chapple carves out an online presence

By Jenn Edwards

With an approach to performance that is casual yet complex, chilled-out but still virtuosic, Julianne Chapple has been building a portfolio of dance works since her late teens, producing her first string of shows in art galleries and bars. Now 33, the founder and artistic director of the Vancouver performance company Future Leisure has a body of work that intersects with photography, robotics, partner acrobatics and, often, with visual art, particularly in collaboration with Ed Spence.

Chapple’s 2017 work Suffix, supported by the Iris Garland Emerging Choreographer Award, incorporated Spence’s large-scale metal sculptures as surreal extensions of the dancers’ bodies, creating an eerily futuristic scene. The black-box theatre was transformed into a starkly lit, abstract laboratory reminiscent of a science fiction movie, placing audience members around the perimeter of the stripped-down performance space. Suggesting human attachment to ever-advancing technology, the dancers moved in and out of duets with a large mirrored ball, a long metal rod, a rounded asymmetrical cage and other objects. Georgia Straight reviewer Janet Smith wrote, “With Suffix, Chapple, working with Spence, has asserted herself as a unique and fearless voice on the dance scene — and someone unafraid to go to dark places in daring and visually bold new ways.”

Chapple has also become a leader within Vancouver’s performance scene by providing affordable studio space to the community. Future Leisure’s home is 45 West Hastings, a downtown hub for performance artists, operated on a membership basis whereby artists pay a low monthly fee for a set number of hours in the space. Operational costs are also covered by open-level classes taught by Chapple and her Future Leisure collaborators, as well as by commercial rentals. Of course, those income sources have dried up due to the pandemic. “The space is what’s weighing most heavily on me right now,” she says.

Before the pandemic effectively brought dance as we knew it to a halt, Future Leisure had an exciting year of creation and performance ahead. First, Shooting Gallery, the company’s biannual mixed program featuring what Chapple describes as “new, weird and wonderful performance-based art” was ready to go for the end of March. Then, in early April, Chapple would have been on her way to perform in Calgary.

The most disappointing postponement was a trip to Berlin. As a 2020 recipient of Dance Victoria’s Chrystal Dance Prize, Chapple was to meet up with Palestinian dance artist Sahar Damoni in the German capital for their collaboration, Pathways Project, in mid-April. Through this new work, the pair plan to explore the intersections between female perspectives within two vastly different cultural contexts: liberal Vancouver and restrictive Shafa-amer in Galilee, where Damoni lives.

Yet Chapple is proving to be adaptable, finding ways to perform to large audiences while social distancing is in effect. “I’m so lucky to be isolating with somebody that is a collaborator,” says Chapple of Spence, her husband, whose work spans photography, digital arts, collage and installation. For years, the pair have been blending mediums to create works that can live comfortably in galleries, small spaces and on film, which has inadvertently prepared them to keep presenting work during a global pandemic.

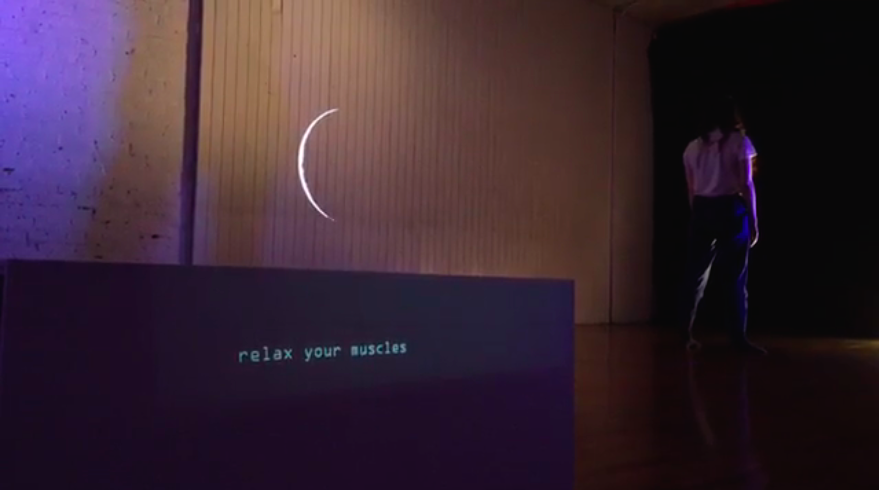

In late March, through the National Arts Centre’s Canada Performs initiative, the duo live-streamed Chapple’s Retracing: we move forward through time from the 45 West studio. Chapple was inspired to submit the solo after noticing an abundance of music on the online platform, and no dance whatsoever. Filmed on an iPhone by Spence, in Retracing Chapple moves her body like a slow-motion wave across a dimly lit white room. In the background, a projected moon slowly moves from a sliver to full. Phrases are projected onto a white box in the foreground, such as “You are different each iteration.” This kind of meditative movement score seems apt in a time when people are isolating in their homes, letting go of their busy pre-pandemic lives and adjusting to a new pace.

In a social media post accompanying the performance, Chapple encouraged viewers to perform their own version of the score in their homes, “moving slowly and deliberately across whatever space you are currently in. Breathe. Focus. Experience time as endless and cyclical.” The performance is viewable on Future Leisure’s Facebook page.

Early April brought another livestream performance, supported by M:ST (Mountain Standard Time Performative Art). Women Appear (and sometimes they learn how to disappear) was originally conceived as a photography project in 2017, and has also been performed in a gallery setting at Latitude 53 in Edmonton. Clad in a blue silk robe, and followed voyeuristically by the camera, Chapple slowly slips through all the crevices of their retro-chic living room, accompanied by hit songs from 1972. Over the course of an hour, she migrates around the room, drinking whiskey, writing thought-provoking notes to her audience, hiding and reappearing as her cat watches nonchalantly from the couch. It’s a clever durational work meant for online audiences to tune in and out, as if walking in and out of a room in a gallery.

As for the future of dance both on and off the internet, Chapple says, “My hope is that this forces people to think more about the context and what the correct framing of different works could be. There is a lot of potential for livestream as a medium in its own right.”

Indeed, what makes Chapple’s approach to performance stand out is a strong awareness of context. She spends a lot of time considering what kinds of settings, mediums and audience configurations will best communicate the images and ideas in her work. For her, dance in the age of Covid-19 isn’t about continuing to produce work simply for the sake of keeping busy, fit and productive. It’s about investigating how our current constraints are reframing dance as an art form, and how choreographers can respond to those changes, on purpose, within their work.