Digital Deluge: Making sense of online dance during the pandemic

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Digital Deluge: Making sense of online dance during the pandemic

By Kathleen Smith

Here we are in August, and art hasn’t disappeared despite pandemic lockdown. But much has changed, including the rules of engagement. As normal cultural activity largely ceased mid-March, many artists went along with the pause, taking an overdue break from the constant motion required by professional dance practices today. Early spring seemed a time of reflection and self-care, a re-focusing on core human values as well as artistic ones.

While some ruminated on the rat race, others put in hours as home-school teachers. Many others, however, pivoted quickly to explore virtual creation and digital dissemination more urgently than before. Dance suddenly became screen-based.

Presenters, company managers and the few publicists remaining on the job looked at re-packaging archived works or works in progress for online consumption as a way to keep the precious cable of engagement alive.

At Toronto’s Citadel: Ross Centre for Dance, artistic director Laurence Lemieux quickly put together Citadel Online, a slickly produced series of works by artists the company had previously presented, with a digital ID designed by Jeremy Mimnagh, who also shot many of the archive videos. In the spirit of the Citadel’s position as a community hub, the series was also a fundraiser for the artists involved.

According to Lemieux, going digital was something they’d already been thinking and talking about. “I spent quite a bit of time last summer doing consultations with a grant from the Canada Council’s Digital Strategy Fund,” she says, “and we were contemplating how to expand to do a virtual Citadel and what that would mean. When this thing hit and we had to cancel so many shows, I thought, we could do nothing, but we could also do something to help. It’s not just raising funds, it’s also engaging with artists so they can get excited about something.”

Some of Citadel Online’s offerings translated to the format better than others. The coolness of screen-based media is generally not a great match for the kinetic qualities of live dance, which often works best with big fat loops of energy passing between performer and audience. Heidi Strauss’ baseline, conceptually all about being in the same physical moment together, converted unexpectedly well. And Peggy Baker’s heart-wrenching memoir of her late partner Ahmed Hassan, Unmoored, gained an emotional buffer by being onscreen, dialling back the most painful moments for the viewer. While this is a good thing for those who don’t wish to be seen weeping in public, I can’t see that extra layer of distance benefitting most digital dance presentations.

Lemieux says that because the Citadel is small, with multiple spaces, it could return to some kind of live business sooner than many others. She envisions micro-performances, socially distanced rehearsals, and possibly a new emphasis as a video production hub offering state of the art equipment and expertise. Though an optimist, Lemieux is also pragmatic. “People say things will never get back to the way they were — and maybe that’s OK. There are a lot of things that we used to do as a society that should change.”

As the pandemic took hold, some companies and presenters amplified their already existing approaches to digital technologies, not only to stay in touch with audiences, but to try and offer a sense of the “liveness” and intimacy that makes performance so vital. There were many, many “living room” videos. These works captured movement and chat in private domestic spaces as dancers, like everyone else, hunkered down at home. There was even a Living Room series, commissioned by TOLive and Meridian Hall in Toronto. Here, 100 artists created micro works (several are more like calling cards, or marketing messages, or calls to arms) for online viewing. Some of these were charming and educational — Santee Smith and daughter Semiah Smith sharing pottery samples and singing, or bboy Michael Piecez Prosserman breaking down break dance in prose and slow motion. A handful, such as tap dancer Travis Knights’ episode, turned out to be little gems of technique and rhythm.

The National Ballet of Canada’s robust digital department also gave viewers glimpses of their star’s home life with regular dispatches. The company, with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, even had a small hit on its hands with Bach to the Barre, a filmed duet by married principals Heather Ogden and Guillaume Côté dancing at home with their young kids.

Funny what works and what doesn’t in the current territory of online performance. Another complete surprise for me was an opening night offering at Toronto’s Luminato Festival, this year’s edition completely online. A live-stream of The Singing Salmon featured soprano Measha Brueggersgosman, at home with her family in Nova Scotia, cooking up a storm of salmon, fiddleheads and roasted potatoes in her kitchen. Once the salmon is in the oven, Brueggersgosman retires to the dining room. It’s clearly golden hour, the setting sun bathing everything in warm light. The camera setup features a view of a river gently flowing past. Brueggersgosman launches into the gospel classic There is a Balm in Gilead. When her young son interrupts her mid-song, she works it into the performance with a singing embrace. Part kooky cooking lesson, part luminous expression of extraordinary gifts, The Singing Salmon was as inspiring as any live performance I’ve seen.

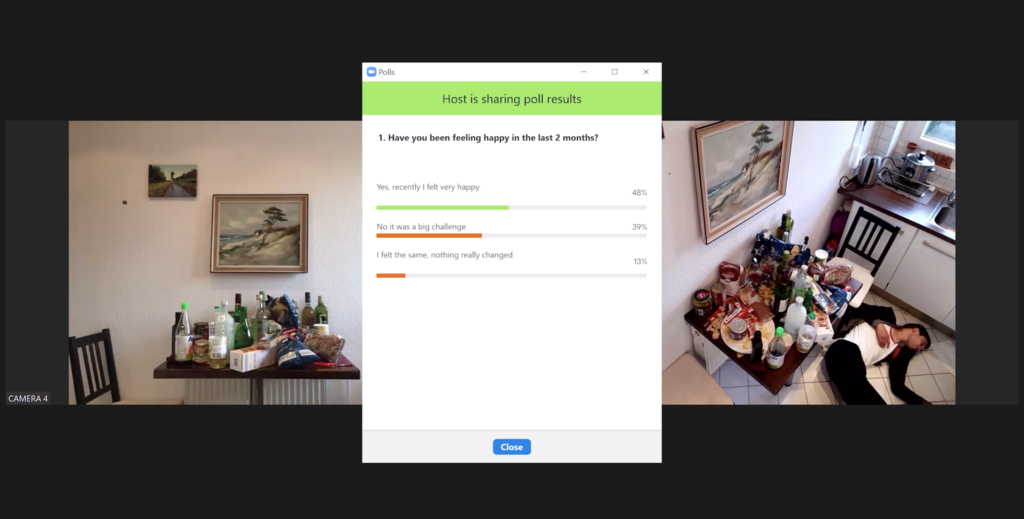

If The Singing Salmon seemed a series of happy accidents, well exploited, a few artists rigorously deployed digital tools in an effort to create something brand new. Aerowaves Twenty20 Frameworks, a European initiative streamed via Zoom, imagined a digital stage for artists to look at “ways to transform the digital medium into their dance partner, rather than as a way of showing their dance works or making dance for the camera.” Of the eight main events, Rooms from Joy Alpuerto Ritter and Lukas Steltner offered some hope for a new way of performing. Live-streamed with multiple cameras (some of them camera phones, wielded with artistry) in different rooms of the performers’ homes, the work employed audience feedback in the form of polls to determine how the narrative would unfold, a kind of choose your own adventure model that also connected the performers with their audience. Though Ritter and Steltner kept things pretty basic (looking out windows, dressing up, sitting down for a dinner date), you could feel the potential for humour and pathos.

Aerowaves boldly looked to the future, but a great many presenters adopted a default approach by focusing on old models of making dance for the camera simply as a way to get work made and seen.

In their response to the pandemic, the Canada Council teamed up with CBC/Radio Canada for Digital Originals, a program designed for moving the performing arts online with micro innovation grants. In the United States, Marquee TV had the good timing to launch as a widely available subscription streaming service in February. Offering documentaries and full-length productions from the likes of Glyndebourne Opera and the Royal Ballet, Marquee TV is also wading into co-commissions. Its first is a doozy — Crystal Pite and Jonathon Young’s Revisor, in a collaboration with the UK’s BBC.

Dance festivals, many caught off guard by the breadth of the shutdowns, pivoted heavily in favour of dance for the screen. Festival des Arts de Saint-Sauveur commissioned 20 films from mostly Quebec-based artists. The series opened on July 5 with Sur la Lame, a collaboration between choreographer Marie Chouinard, composer Louis Dufort and performer Valeria Gallucio. The festival continues into September with free weekly premieres.

Some of these initiatives feature a business as almost usual hopefulness that doesn’t seem to recognize the upheaval of the times. An accelerating push for a universal basic income and an end to racism and the unfettered marginalization of society’s most vulnerable has gained mainstream traction as injustices gain exposure — these ideas and movements are impacting communities in huge ways. There is also a new linked scrutiny on the way economics drives the making of art. It’s becoming clear that many artists believe change is long overdue.

Don’t believe it? Check your Facebook feed. Here, cross-Canada dancer-to-dancer discussions often highlight the frustration many artists (and non-artists) feel. Community activists such as dancer and Black Lives Matter co-founder Rodney Diverlus in Toronto and choreographer Lee Su-Feh in Vancouver are followed on social media as much for their leadership and information-sharing as they are for their performance careers.

Lots of us are on these video-friendly platforms and use them daily to keep up with friends and family. So it’s not a stretch from catching up with friends or gleaning deets of this weekend’s protests to posting or watching a snippet of choreography online, or taking part in a chat or a challenge about some aspect of creation. From there it’s a short step to virtual residencies like the ones hosted by Montreal’s Centre de Création O Vertigo, or the many virtual dance parties on Facebook and Instagram. These informal methods of presentation and sharing offer at least some of the warmth that’s been missing during the lockdown.

Social media’s immediacy is also being harnessed by larger institutions like the National Arts Centre, whose #CanadaPerforms is a two-year partnership with Facebook Canada. Dance duo Allen and Karen Kaeja presented their 27-minute Fallow as a Facebook Livestream in May, performing live to camera from self-isolation in Sauble Beach, Ontario. In the early days of the pandemic, Facebook and the NAC-hosted #CanadaPerforms website offered “replay” videos from more than 600 Canadian artists, including Montreal’s George Stamos and Edmonton hoop dancer James Jones.

Toronto Dance Theatre’s artistic director Christopher House’s June retirement after 42 years with the company was a digital gala affair on YouTube. While his filmed interpretation of Deborah Hay’s News was a perfectly programmed goodbye embedded with numerous nods to what’s yet to come for the master choreographer/performer, the video tributes to House were a tease. They only hinted at the celebratory tears and laughter and kudos we all should have been sharing in person. The viscerally social part of performing arts, the humanness of it, was sorely missed.

So. Is dance going to be fully digital going forward? That would be a shame. The biggest problem for me as an audience member is that while going to a live performance often feels like a celebration or a small transformative event, watching dance online often, or even mostly in these days of inundation, feels like work.

Of course artists need to stay active, and to keep expressing their ideas, but is the current barrage of online material really going to fill the void left by quarantines and shuttered theatres? Much of it doesn’t even make the best use of the digital tools that are available. Cameras and editing suites have become so user-friendly that it’s easy to forget they are only tools, a means to an end, surely not the end itself?