Master Coach: Héctor Zaraspe, and his work with Fonteyn and Nureyev

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Master Coach: Héctor Zaraspe, and his work with Fonteyn and Nureyev

By Gabriela Estrada

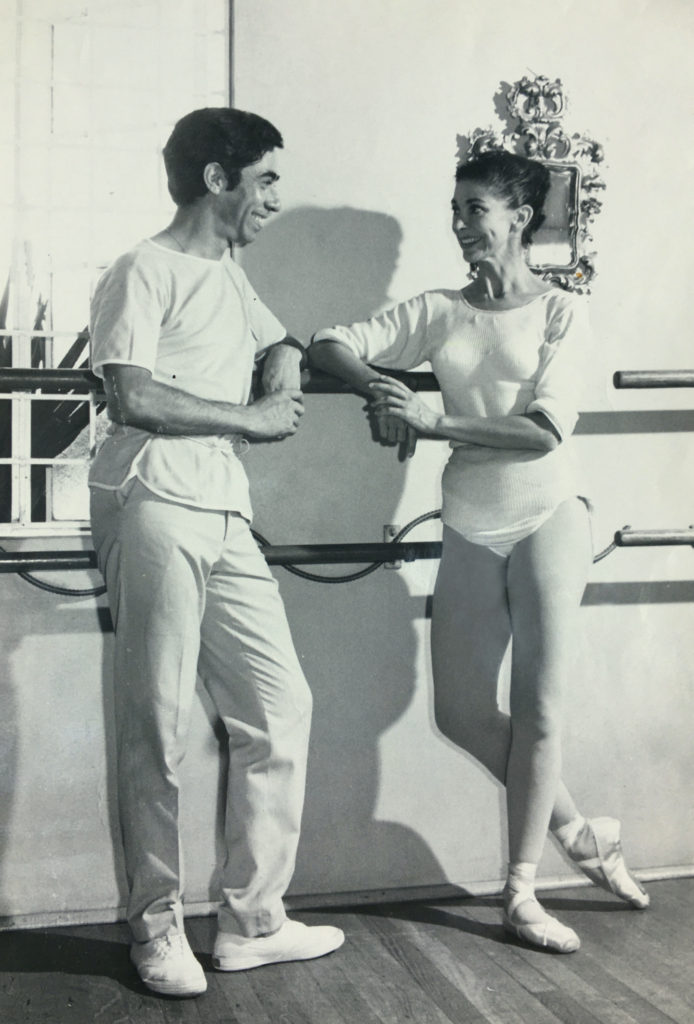

Last June, Héctor Zaraspe missed his 90th birthday celebration due to the COVID-19 lockdown. Earlier, he also missed the presentation of the annual choreography prize named after him by the Juilliard School, where he taught for 35 years. Maestro Zaraspe has also coached some of the greatest ballet and Spanish dancers of the 20th century, notably Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev. How did he get there?

As a child growing up in Tucumán, Argentina, Zaraspe participated in school productions, singing and dancing. In his teens, he moved to Morón, located on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, where he studied piano, theatre and contemporary dance. Upon turning 18, Zaraspe took an accelerated training program for male dancers at the Teatro Colón’s ballet school. Gema Castillo — a ballerina at Teatro Colón and a respected teacher at the school — eventually entrusted him to teach her classes, and Zaraspe eagerly applied his pedagogy discoveries at his own studio, ABC Ballet, which he founded in Morón.

In 1954, at age 24, Zaraspe moved to Spain, where he taught ballet for children and adults, novices and professionals at Madrid’s Amor de Dios studio. That’s where he met Mariemma, an acclaimed Spanish dancer who was instrumental in the transformation of professional Spanish dance training. At the time, it was rare for flamenco artists to take ballet classes but Mariemma, who had trained at the Paris Opera, asked Zaraspe to give her private lessons and join Mariemma Ballet de España as ballet master. Soon, Zaraspe’s following grew among emerging and established Spanish dance artists, including the great Antonio (Antonio Ruiz Soler).

It was his work with Antonio y sus Ballets de Madrid that led Zaraspe to meet the recently defected Soviet ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev and British prima ballerina Margot Fonteyn. In 1964, Antonio’s company performed at London’s Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, where Luis Fuente danced Sonatas, an elegant virtuoso solo with intricate allegro in the bolero style. After the opening night performance, Antonio’s producer, Sandor Gorlinsky, who also represented Nureyev and Fonteyn, hosted a dinner to which the ballet stars were invited. When Nureyev discovered Zaraspe was responsible for Fuente’s outstanding training, he announced that he wanted to take classes with him, too.

The following year, Nureyev and Fonteyn toured with the Royal Ballet to New York City, where Zaraspe had recently moved. After taking Zaraspe’s class at the Joffrey Ballet, Nureyev said he would attend the next day. Since the premises were closing for the Easter holiday, Zaraspe was given a key to the building, enabling him to offer Nureyev his first private lesson. The following week, when Zaraspe went backstage to congratulate Nureyev and Fonteyn for their performance in Giselle, Fonteyn said she wanted to take classes with him, too. That was the start of a collaboration that Zaraspe would come to cherish.

Zaraspe is often asked what he taught Fonteyn and Nureyev during their classes. “I was not there to ‘teach’ them,” he explains. “During their performance season, I would give them a very simple class. I would start gradually, deliberately warming up the articulation of the feet and preparing the joints for turnout, allowing the dancers to focus on the spine’s placement, without any fancy port de bras. As the barre progressed, I would incorporate transfers of weight and changes of alignment.” On days when they were not performing, Nureyev would ask for a “black step.” This, says Zaraspe, meant he wanted a special challenge. “So, I would create virtuoso combinations with lively music like the jota.”

In terms of coaching, Zaraspe says what he does is artistic direction. “I would suggest artistic choices and offer recommendations that would enhance their expressive communication on stage. For example, one day in rehearsal, when Margot was preparing for the scene where Juliet’s mother presents the dress she is to wear, Margot [as Juliet] would bring the dress towards her chest with one hand while holding a doll with the other. I suggested she drop the doll as she held the dress against her chest with both hands, indicating her transformation from a child to a young woman. She appreciated details like that.”

In the documentary film I Am a Dancer (1972), Zaraspe is seen giving a class to Nureyev. In one scene, Nureyev performs a développé à la seconde as preparation for a pirouette en dedans from second position, after which Zaraspe gives him notes. The scene provides a rare and welcome glimpse of the mutual respect in the working relationship between the ballet star and the master coach.