By Michael Crabb

Thanks to Digidance, an initiative by a consortium of major Canadian dance presenters, a new generation will this month have the opportunity to see why Jean-Pierre Perreault’s 1984 work Joe is considered a landmark in the evolution of Canadian contemporary choreography.

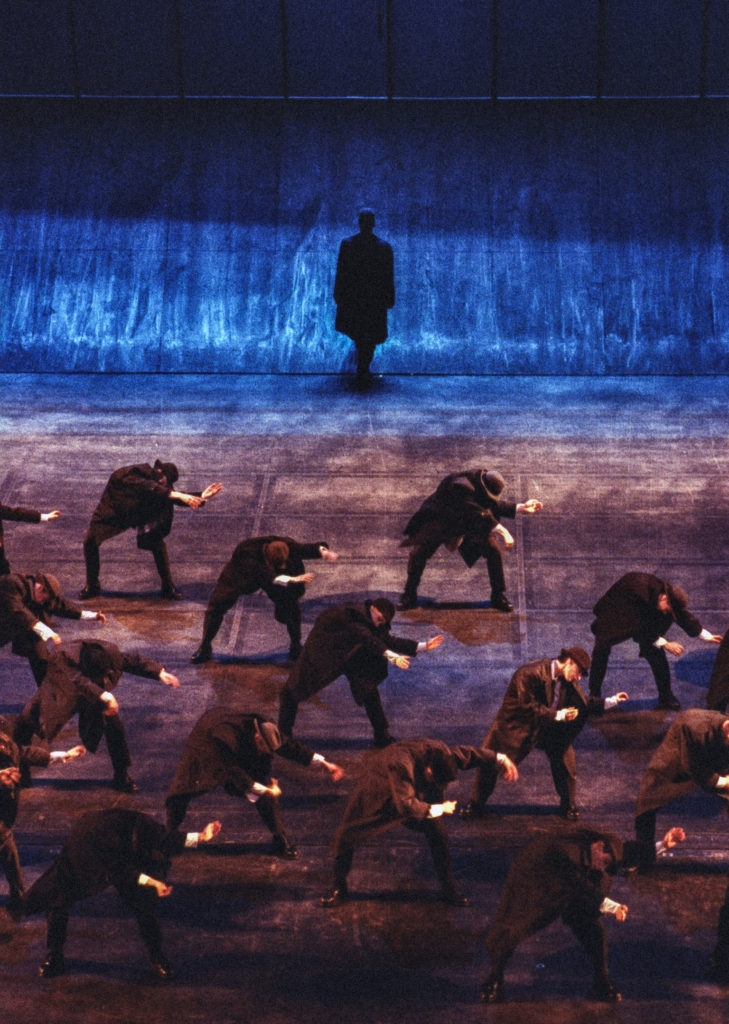

Perreault, who died in 2002 at age 55, originally made Joe for 24 students from Université du Québec à Montréal. In a bleak quasi-industrial setting, Joe in its expanded professional remount pitched 32 drably-clad dancers in black boots onto a stage steeply raked front and back, overlooked by huge sloping skylights. For more than an hour, to the tattoo stomped by its collective feet, this human mass eddied to and fro or surged up toward the skylights as if in search of an escape, only to recede defeated. Individuals sometimes broke from the crowd.

Joe always evoked varied responses. It can be read as a grim image of human oppression or of herd mentality and conformity. It may also be seen as a tribute to human resilience. More generally, it reflected Perreault’s fascination with the way environment shapes human behaviour. “For me,” Perreault wrote, “choreography is the expression of space, as dance is the expression of the body.”

The sheer scale of Joe made it hard to tour and Perreault was anyway not one to dwell on repertoire. He was primarily an experimenter. Joe was last produced in what was billed, sadly but in all likelihood accurately, as a farewell tour in 2004. Fortunately, it was captured in broadcast quality for posterity by the CBC in 1995 and can now be seen during a one-week online Digidance viewing window, March 17-23.

When pandemic lockdowns began in Canada a year ago, it was soon clear that audiences would not be returning to theatres as quickly as was optimistically first thought. In what might be called The Great Pivot, performing artists and producing companies, being of necessity resilient and adaptable, began exploring ways to engage with their audiences virtually. The internet was soon flooded with new and existing programming, the quality of which ran the gamut from excellent to embarrassing, much of this discrepancy accountable less to talent than to widely varying production limitations.

But what about dance presenters? They also have audiences and stakeholders. They, too, must find ways to maintain a presence. Canada’s dance presenters, while they may steer their own courses according to local circumstances, do not exist in geographic isolation. They maintain networks. They talk to each other. They often collaborate.

It was with this in mind that in the pandemic’s early days Jim Smith, artistic director of Vancouver’s DanceHouse, sent an exploratory email to colleagues across the country. While each presenting organization had its independent online initiatives, what, Smith wondered, could they do collectively that would serve their audiences and maintain a profile for themselves and the art of dance? After much exchanging of messages, a formal meeting was held online in June and, then, on a weekly basis.

Trial balloons were floated. In October a group of presenters, including the four that would eventually constitute Digidance, collaborated in the Canadian online premiere of Dancing at Dusk, an extraordinary performance of German choreographer Pina Bausch’s version of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, danced on a beach in Toubab Dialaw, Senegal, by a specially assembled company of 38 dancers from 14 African countries.

It resonated,” says Cathy Levy, executive producer of dance at the National Arts Centre. “It kept us talking.”

The following month, Montreal’s Danse Danse, in collaboration with Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre, the National Arts Centre and DanceHouse, presented Jack of All Trades (JOAT), a Montreal-based street dance platform, in a livestream battle. Given the issue of livestream programming in a country with five time zones, JOAT Battle was recorded and made available for 24 hours.

Digidance, as these four presenters subsequently branded their digital programming consortium, was designed to fill a gap in the online marketplace by offering audiences work they might not otherwise see in recorded performances of the highest possible technical and aesthetic quality.

Digidance’s first official offering, which had a one-week run in February, featured the Paris Opera Ballet in 2019’s three-act Body and Soul by Vancouver-based choreographer Crystal Pite.

Launching with such a prestigious company — one that rarely puts pointe shoes to floors in North America — dancing in the Canadian premiere of a work by an A-list choreographer was a masterstroke. It probably would not have happened had it not been for the fact that Smith, through his cultural management company Eponymous, is also Pite’s agent and thus already had close contacts with Paris Opera staff. “They were very supportive of our initiative,” says Smith.

The Digidance consortium was also concerned to provide context and enrichment for audiences. So the 75-minute Body and Soul digital presentation was preceded by the informative equivalent of a pre-show panel discussion produced in Vancouver by DanceHouse. An online workshop with long-time Pite dancer and choreographic assistant Jermaine Spivey could also be accessed for an additional payment.

Digidance’s four presenting organizations share licensing and other costs equally. Ticket revenues accrue to the point of sale, although nobody is expecting to get rich on digital programming. “It’s about keeping dance in the hearts and minds of our audiences,” says Levy.

It is remarkable how adept artists and arts organizations have been in confronting the challenges presented by a prolonged shutdown of live performance. Some had already recognized and embraced the need for an online presence. Others had to start from scratch. Regardless, when this nightmare is behind us, one positive legacy may be a broad recognition that while live performance remains central, a digital presence that complements, enriches and extends that core activity is indispensable. It will be part of “the new normal.”