New York: A year of dance from the privacy of home

- Home

- City Reports 2020 - 2023

- New York: A year of dance from the privacy of home

By Robert Greskovic

Finding dance during the lockdowns and shutdowns necessitated by COVID-19 protocols has made viewing dance a catch-as-catch-can venture. But, looking back over the past 12 months, I happily recall some notable highlights that streamed into my living space in midtown Manhattan.

Starting in April 2020, the Martha Graham Dance Company began an often rich series of changing streams featuring an array of footage documenting Graham’s art and artists, largely under the title of Martha Matinees. The keystone of the first “matinee” was a rare and largely unknown, circa 1944 black-and-white silent film (with sound added) of the choreographer’s now iconic, Aaron Copland-inspired Appalachian Spring. The filming, with one unmoving camera, records the full stage with the complete ballet performed by its original cast, including an unforgettably intense Graham as The Bride. The still on-going series began with free access and has since evolved into one accessible for a fee.

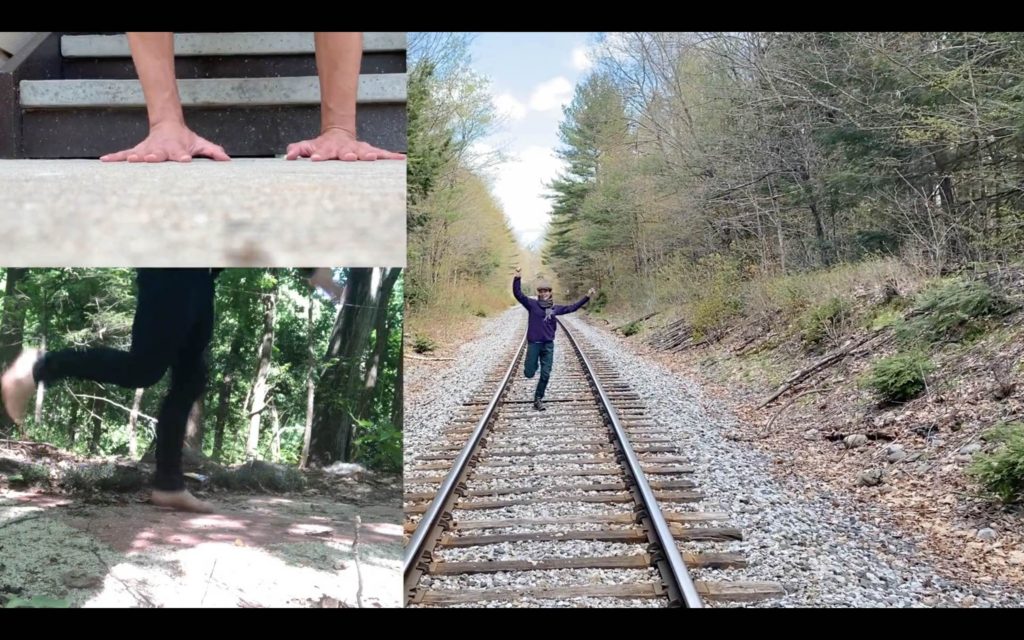

In June 2020, a 58-minute program of four video dances made especially for the occasion by Mark Morris for his Mark Morris Dance Group was framed by snappy chat from the choreographer himself. The presentation gave a sense of what would become a familiar look during the year of COVID: the documenting of individual or cohabitating dancers isolated and in what might best be called Zoom rectangles.

The “stepping, walking, running and hopping” that Morris specifically tasked his chosen dancers to do in Sunshine are familiar elements of his stage choreography, and it wouldn’t be surprising if this videodance, to Gene Autry singing You Are My Sunshine, makes its way with apt adjustments to the stage when the company is back on the boards.

New York City’s two major ballet companies have been providing samplings of work streamed to audiences at home: New York City Ballet had a wide array of full ballets to stream; American Ballet Theatre, more or less none. As balletgoers began to wonder why this difference existed, we learned that NYCB, with its official home in Lincoln Center’s David H. Koch Theater, has a store of films made for archival purposes due to standing arrangements with the various unions working regularly in their home theatre, where the works were recorded. ABT, having no permanent home and thus no regular agreement in place to film its works for archival purposes, had to find alternatives to capture an online audience.

New York City Ballet’s weeks-long “digital seasons” launched last spring and continue into this one; each has included an array of archived films of the company’s varied repertoire. The fall instalment included 25 selections from the troupe’s well-known Balanchine and Robbins repertoire, as well as recordings of more recent works by Alexei Ratmansky and Justin Peck. Five short premieres served as calling cards for their commissioned choreographers who are slated, as of now, to create full-scaled works for the NYCB season planned hopefully for fall 2021. Of this quintet, Pam Tanowitz and Peck held out the most promise for the new ballets.

As 2021 unfolded with social distancing restrictions still in place, the ABT Studio Company, essentially American Ballet Theatre’s apprentice group, presented a two-program stream of works, two of them world premieres, all created and rehearsed during the fall outside New York in “ballet bubbles.” Particularly vivifying in the streamed presentation billed as a Winter Festival was Escapades, an impressively deft choreographic display by New York freelancer Amy Hall Garner. Her fluid and eye-catching choreography takes inspiration from music by Ezio Bosso and Guy Sigsworth to showcase eight of the group’s 14 talented dancers.

In early March, Dancers of the Met presented two evenings with two shows per night, in collaboration with members of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Met Chorus Artists, who have been furloughed since the opera suspended performances around this time last year. The small-scaled live event indicated a baby-step return to the once-usual showing of dances and dancers with live music. The mixed bill of new works — a recording is available here — each created in the five days leading up to their presentation, was performed in a bare-bones studio setting, in front of a limited, physically distanced audience of 16. Of course there were face masks for performers and audience members alike, but these didn’t stifle the frisson connected to performers playing directly to indoor spectators, blissfully free of the now ubiquitous barrier of a video screen.

Of the works on display, Emery LeCrone’s seven-minute Tristesse, dedicated “in loving memory of ‘Uncle Jack’,” presumably the choreographer’s relative, was dark-toned and dramatically effective. Set to musical selections by Johannes Brahms and Gabriel Fauré, sung and played artfully, LeCrone’s lament-like composition had her couple of dancers intermittently sinking to the floor.

In an intimate setting, the choreographic moves of Tristesse — particularly those that left the dancers lying more or less at my feet — made the singularity of live dance in real time so affecting, especially after so much time watching dance at an unbreachable distance on a screen at home.