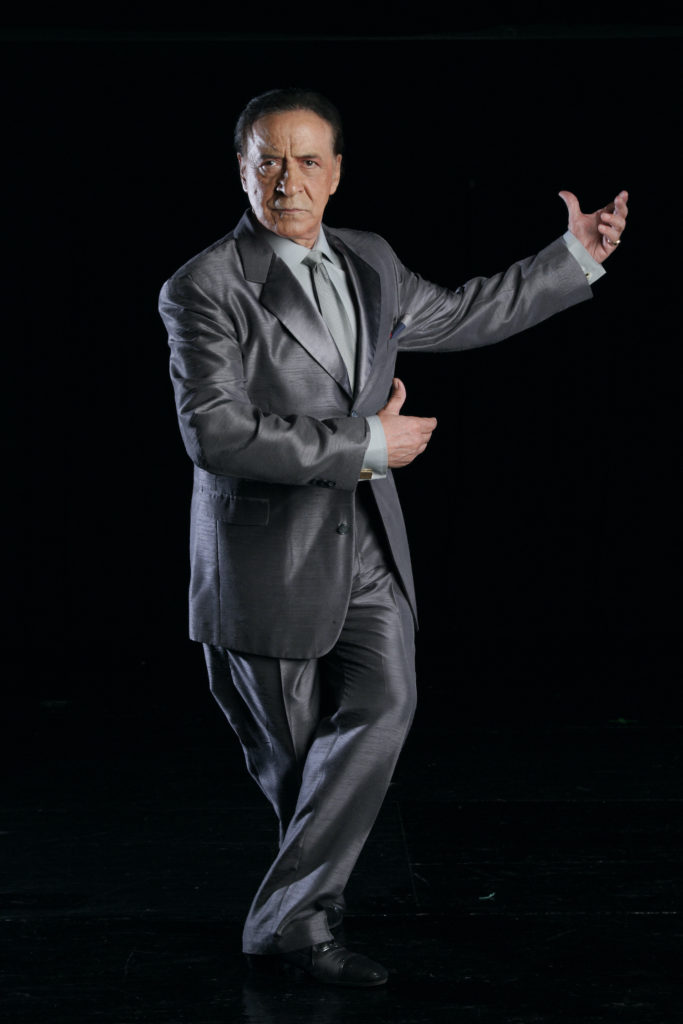

Passages: Juan Carlos Copes expanded the potential of Argentine tango

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Passages: Juan Carlos Copes expanded the potential of Argentine tango

By Victor Swoboda

The death of Juan Carlos Copes on January 16, 2021, at the age of 89, focused well-deserved international attention on the Argentine dancer/choreographer — over his career, Copes not only sparked worldwide interest in the Argentine tango, but revealed its potential as an art form of depth and variety. With directors Claudio Segovia and Hector Orezzoli, Copes put together a show of dancers, singers and musicians called Tango Argentino that had an unexpectedly resounding premiere in Paris in 1983. Sold-out success followed on its 1984 European tour and 1985 North American tour, which stopped in three Canadian cities before registering a triumph in New York.

Copes was 52 in 1983, and his equally celebrated partner, Maria Nieves, was not much younger. They had been dancing together for more than 30 years, a married couple for nine of them. Neither had formal training — tango in their day was learned in dance halls — yet both were highly conscious of how to present their body lines. Supremely elegant, Copes had a distinctive soft step and economy of movement that never betrayed effort. Despite considerable marital woes, Copes and Nieves on stage displayed remarkable respect for each other, which translated visually into choreography of great dignity. Dignity defined not only their serious numbers, but their humorous ones, as well. Tango Argentino audiences discovered that along with battle-of-the-sexes passion, tango had a comic side and could accommodate different moods and situations.

Some Tango Argentino couples were flamboyant crowd-pleasers. Gloria and Eduardo executed leaps. Nelida and Nelson performed dips and sensually intermingled legs. Many reviewers praised the verve of Tango Argentino, but The New York Times’ Anna Kisselgoff — a critic with a discerning eye for classical ballet and contemporary dance — noticed the distinctive quality in Copes’s and Nieves’s dancing that gave tango a layer of depth not matched by the other couples. She wrote: “They dance as one, and the passion they exude seems completely understated by comparison with their more exuberant colleagues; it is there, subsumed but present.”

Kisselgoff could have been writing not about a tango couple but about a celebrated ballet pair like Erik Bruhn and Carla Fracci.

Copes and Nieves put on their first show in Buenos Aires in 1955. A producer then presented them in Europe and, in 1959, at New York’s Waldorf Astoria. They were standouts in a Broadway variety show called New Faces of 1962, where Herald Tribune critic Walter Kerr wrote, “They have literally given the tango a new twist.” Ed Sullivan then invited them to perform on his popular national television show. Capitalizing on the exposure, Copes organized a small precursor of Tango Argentino called Juan Carlos Copes and his Tango Ballet that played in 1962-1963 at Chicago’s Edgewater Beach Hotel and New York’s famous Roseland dance hall.

During Argentina’s dictatorship period of the 1970s, Copes was staging shows in Buenos Aires, struggling to keep tango’s tradition alive despite pop music’s ascendance. When constitutional rule returned in 1983, the climate was better for Copes and his team to produce Tango Argentino. Many others followed its example, most notably Tango por Dos created by Miguel Angel Zotto and Milena Plebs. All can trace their heritage to Copes.

An indomitable artist, Copes continued to teach and to perform until 2015, often with Johana, his daughter by his second marriage.

With his chiseled face and easy air of confidence and command, Juan Carlos Copes had undeniable charisma and a powerful stage presence. But he did not subscribe to the general public’s notion of a macho tanguero, and was not embarrassed to confess that he felt moments of such joy when dancing that he wanted to cry.