Ghost Light: Neumeier’s pandemic ballet

- Home

- Reviews 2020 - 2023

- Ghost Light: Neumeier’s pandemic ballet

By Michael Crabb

In early September, while North American ballet companies were still adjusting to the extended closure of theatres, their German counterparts were retaking the stage. The constraints of public health directives meant limiting the number of dancers who could appear at any one time — no Kingdom of the Shades from La Bayadère — and partnering could only occur among those in domestic bubbles; but still, it was live performance for live audiences.

Some companies opted for gala-type programs of solos and pas de deux. The more ambitious, such as Munich’s Bavarian State Ballet, chose to mount popular full-length classics. In their case, it was Giselle and Swan Lake, although that necessitated drastic pruning of the big ensembles.

John Neumeier, now in his 48th year as artistic director of Hamburg Ballet, decided to do things differently and, despite all the restrictions, give his dancers the artistic stimulus of making something new. Starting in May 2020, Neumeier began work on a full-evening ballet both practically and metaphorically informed — you could almost say inspired — by the pandemic. Then the 82-year-old choreographer hit on an emblematic title, Ghost Light, referring to the single lamp traditionally left alight onstage when a theatre is otherwise dark. Such a device occupies a position mid-stage and left of centre throughout the ballet. At the start, a pair of pointe shoes lies discarded beside it; point taken, so to speak.

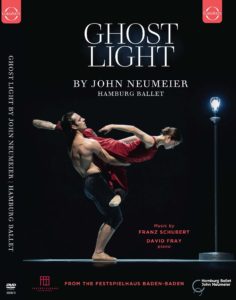

Subtitled A Ballet in the Time of Corona, and with the dedication “For my dancers,” the 100-minute work, performed without a break to live solo piano, all Schubert, was given its public premiere in Hamburg on September 6 and then toured. It was live-streamed from the Festspielhaus in Baden-Baden in mid-October and in its recorded version was recently offered on demand online by Hamburg Ballet. It is now available on an all-regions DVD at Presto Music, and can be seen in a trailer here.

For those who associate Neumeier primarily with spectacular story ballets, Ghost Light will come as a refreshing non-narrative and, in terms of decors, almost minimalist surprise. Neumeier has explained that because of public health guidelines, the ballet had to be made with small groups and in parts. These were later assembled as a series of vignettes, sometimes overlapping and occasionally re-quoted.

Ghost Light, though rid of narrative frippery, is not devoid of drama. The opening section, to the andantino second movement of Schubert’s six Moments Musicaux, references the over-the-top passion of Neumeier’s own Lady of the Camellias. Later we meet the heroine from his version of The Nutcracker, prompting a cheerfully innocent encounter with her uniformed cavalier.

Ghost Light crackles with erotic tension. Canadian Félix Paquet spends much of the ballet in open-shirted and unrequited pursuit of Christopher Evans (a former contemporary at the National Ballet School of Canada). Matias Oberlin and David Rodriquez are luckier in a duet that drips with scarcely repressed romantic longing. Among the more prevalent different-gender duets, those for Hamburg veterans Silvia Azzoni and Alexandre Riabko, and for principal Madoka Sugai and corps member Nicolas Gläsmann, are particularly striking in their inventiveness.

Loss and absence are not the easiest conditions to convey in any art form, yet Ghost Light often succeeds in evoking the impact the pandemic has had on so many lives. Two dancers exchange yearning looks, but know that for now that’s as close as they can get. Two friends run toward each other as if to hug, then suddenly stop short. An ethereal Giselle character wanders alone: no Albrecht, no Wilis.

Often, ensembles act as backdrop to these featured duets or to brief buoyant solos by younger dancers such as Atte Kilpinen. The choreography, ranging in style from full-on classical to Neumeier’s more characteristic neo-classicism, fits both the music and the dancers like a glove. It frequently has a spontaneity and energy that gives certain passages, much to their advantage, an almost improvisational look.

Neumeier’s is a gifted company that comprises different physical types and abilities, and a balance of artistic maturity and youthful rambunctiousness. They perform Ghost Light with total commitment and focus.

Ballets made for live performance do not easily translate to the screen. Ghost Light is no exception. That said, television director Myriam Hoya, working with stage lighting and fewer camera placements than one imagines she’d have liked, does an excellent job of finding interesting angles and of balancing long shots with close ups. There’s never a jarring switch. Ghost Light has few longueurs and when silent pauses occur, it’s probably so the brilliant French pianist David Fray can stretch his hands. That said, time passes differently when you’re watching a screen instead of a live performance, and Ghost Light in this context is too long. Yet, it’s hard to decide precisely what might have been cut. The better option for viewers is to do what live audiences cannot and take a break half way through.