Inspired by Pavlova: Malvina Hoffman’s Bacchanale frieze

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Inspired by Pavlova: Malvina Hoffman’s Bacchanale frieze

By Didi Hoffman

Blame it on the Bacchanale. Or rather, celebrate the Bacchanale, danced by the great Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, whose performance inspired a young American sculptor, Malvina Hoffman, to spend years creating a magnificent frieze of this iconic duet. Hoffman would go on to become “one of the few women to reach first rank as a sculptor,” as the New York Times said after her death in 1966. (Full disclosure: Malvina Hoffman was my husband’s great aunt.)

The historic record is hazy, but it is likely that the Bacchanale began life as part of Mikhail Fokine’s Cléopâtre. Set to Glazunov’s Autumn movement of The Seasons, it featured a group of women pursued by a satyr. Later, Fokine reworked the piece as a pas de deux, which premiered in Saint Petersburg the following year with Pavlova and Laurent Novikoff. Another version of the Bacchanale was arranged by Mikhail Mordkin when he partnered Pavlova, and it is this version that became one of the ballerina’s signature works.

Keith Money, in Anna Pavlova: Her Life and Art, reconstructs a performance of the Bacchanale, in which Pavlova, “so petite and lissome,” and Mordkin, “well formed and virile,” swept onto the stage, then “let their billowing veil drop, threw rose garlands at one another, ducked and twisted with almost animal vigor, and even went into kissing clinches … Together they struck gold, in this autumn bacchanal, which proved itself a display of finely tuned eroticism.”

Hoffman, who was living in Paris while studying under Auguste Rodin, saw the duet in 1910, at the London Palace Theatre premiere of the Ballets Russes. The experience left her with an obsession to sculpt the ballerina. She purchased tickets to every other performance during her time in London, and stood in the aisles drawing the different movements of Pavlova and Mordkin.

In 1912, Hoffman’s Russian Dancers, inspired by Pavlova, won first prize in the prestigious Paris Salon for its very modern way of showing movement in bronze for the first time. The bronze recreates Pavlova and Mordkin dancing the Bacchanale and you can feel the energy of their movements pushing them forward. The way their momentum and the lightness of their dancing is captured in the heavy medium was groundbreaking.

Hoffman wouldn’t meet Pavlova until 1914, when both women were in New York. Pavlova was on a tour supported by Otto Kahn, chair of the board of New York’s Metropolitan Opera. A German native, Kahn missed the European arts in New York City, where he had immigrated, and after seeing Pavlova and Mordkin’s Bacchanale at its Paris premiere, the overwhelming reaction of the audience convinced him they must dance at the Met. He felt it was his responsibility to bring them to the United States.

When Kahn’s wife invited the two women to her home for tea so they could meet, Pavlova graciously invited the sculptor backstage to rehearsals. After this, Hoffman’s study of the dance and the ballerina became more intense; she also began to learn Russian. Pavlova corrected Hoffman’s drawings, helping her perfect the arch of a pointed foot or the gesture of a hand. Hoffman encouraged the criticisms, and a friendship ensued.

On her return to Europe, Hoffman designed many of Pavlova’s posters and playbills, while continuing to sculpt the ballerina in dance poses, welcoming critiques from Rodin. In Hoffman’s memoir, Yesterday is Tomorrow, she recalls her discussion with Rodin about the bas relief frieze of the Bacchanale, which he called “a great thing of beauty, like the Greeks created.”

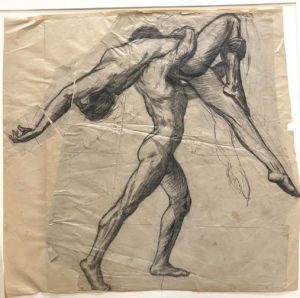

The plaster frieze broke down the dance into 26 panels, each one featuring a pose by Pavlova and a partner. Working sessions would take place whenever she and Hoffman were in the same city. Hoffman was allowed to photograph many of the poses, and in some of them, you see a playful, laughing Pavlova. She found this time relaxing, even though they might work well into the night after a performance or long rehearsal had ended.

In 1919, Hoffman became the first woman ever installed in the Paris Luxembourg Gardens with her over-life-size bronze sculpture, titled Russian Bacchanale, which features Pavlova and Mordkin holding aloft a billowing veil.

Anna Pavlova died unexpectedly in January 1931. Only weeks earlier, she had visited her friend Malvina Hoffman’s studio in Paris. Hoffman saw she was ill and begged her to slow down and rest, but Pavlova would never disappoint her audiences and continued to perform. When Pavlova died of pleurisy soon after, her manager called Hoffman to help him with the arrangements. Hoffman was so bereft at the death of her muse that she wrote in her diary, “My light is blotted out.” She kept the frieze of the Bacchanale, which had taken 15 years to complete, in her studio for the rest of her life.

After Hoffman’s death, her estate gifted the entire Bacchanale frieze to the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art in Iowa, where it is displayed on a wall in their library.