Sharing Worlds: Live theatre’s mysterious “more”

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Sharing Worlds: Live theatre’s mysterious “more”

By Jeannette Andersen

During Germany’s first pandemic lockdown in March 2020, my initial reaction as a dance critic was, “Now I will watch all the performances online for which I usually do not have the time.” But very soon I found my attention trailing off. I got bored, whether I sat in front of my computer or my 40-inch TV screen. Hans van Manen’s Black Cake was just some dancers rambling about pretending to get drunk on champagne. Yet as the finale of a triple-bill evening, Black Cake can be an exhilarating experience. Sheepishly, I confessed my disengagement to some colleagues and to my surprise most of them felt the same way.

Choreographers recognize this problem. At the Dance 2021 festival in Munich, which took place during a lockdown, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Emanuel Gat declined having their works that were made for the stage livestreamed, arguing the pieces would not work on the screen.

With increasing withdrawal symptoms from the lack of live theatre during each lockdown, I did some research about what makes seeing a stage performance live compared to livestreamed so different.

Renowned Bournonville scholar Erik Aschengreen, who was a critic for 41 years, said in a recent Danish film, En Anden Verden — et portræt af Erik Aschengreen (Another World — a Portrait of Erik Aschengreen): “When I go to a performance, I enter a different world.” He has, he says, “a physical response … When you leave a Bournonville performance you should experience a lightness in the body and have the feeling that you can dance … which of course only lasts until you have to run to catch the bus.”

Some scientists compare going to a performance with participating in a ritual. You might change your clothes before leaving for the theatre, a place you visit with no other purpose than to watch a performance. Usually, the auditorium lights are dimmed, and external disturbances are eliminated. Importantly, you get to choose what to focus on, unlike watching a filmed performance, when the camera chooses for you. This can be irritating, as in a recent film of a stage performance of Swan Lake: the camera zoomed in on Odette’s and Prince Siegfried’s faces just when I would have preferred to see them in a longer shot amidst the flurry of swans.

Live theatre is also a physical experience. Neuroscientists have found that when many people are gathered together their heartbeats and breathing synchronize. Others have found that watching a dance performance, you respond viscerally to the dancers’ movements, as if you yourself were dancing. When I see what I consider a perfect movement, I momentarily stop breathing.

There is a much more casual approach to watching a performance at home: you can loll on the couch in sweatpants, chat with friends on your mobile phone, and stop the performance at any time to get a snack.

Many studies have measured the reactions of viewers sitting in front of a screen watching dance, but fewer elucidate what happens between the audience and the dancers in the theatre. This is difficult to measure because a performance happens over time, during which a complex exchange takes place between audience and dancers. Some researchers have tried to figure out what exactly happens by asking test subjects for responses to questionnaires filled out after the show, but that only measures what the person remembers and not their actual moment-by-moment reactions. In other studies, test subjects were asked to press buttons when experiencing certain responses during the performance, which, however, limits the response to the researchers’ preconceived notions.

Within the last few years, neuroscientists have become increasingly interested in this exchange between audience and dancers. One group from the University of Paris tracked the correlation between the dancers’ movements and those of audience members by filming both during a performance. Their study, published in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, found that the stiller the audience, the higher their concentration. The dancers made bigger movements when the audience moved the least.

Neurolive, a research project funded by the EU and running over five years, brings together artists, scientists, and audiences in order to investigate what sets live experiences apart from recorded or streamed ones. So far, they have held a symposium and a weeklong workshop, presented a dance production during which audience members were asked to wear an EEG cap to capture brain activity, and hosted a salon in which guest artists initiated conversations on different ways of understanding and investigating liveness.

In Munich, at the Bayerisches Junior Ballett’s first performance after two years of lockdown, director Ivan Liska said from the stage before the start of the show: “The dancers have missed performing in front of an audience because the audience sends waves to the dancers and vice versa. This mutual exchange creates an aura, and,” he added, pointing toward the auditorium, “that aura is right there.”

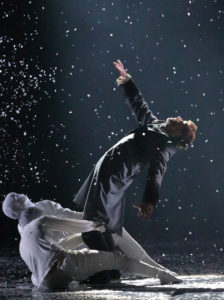

Andrey Kaydanovskiy created The Blizzard for Bayerisches Staatsballett during a lockdown in 2021. Before the premiere, I interviewed him, and we talked about live performance versus streaming. Kaydanovskiy said, “If the piece is streamed, we do not feel or hear the response from the audience.” However, during a live show, there “is quite an energy when 2,000 people are watching you. You feel it, it gives you power, and you dance against it.”

This kind of exchange does not take place when watching a performance on the screen, which is perhaps partly why it often becomes boring. But further research remains to be done in order for us to understand exactly what this inexplicable more, this magic, is, that develops when audience and dancers are in the same space.

~Tips for bringing “more” to livestream viewing

Streaming has become a vital part of the dancescape since the outbreak of COVID-19, with the potential to reach a much larger audience. Vancouver’s DanceHouse, part of a Canadian Digidance initiative enabling audiences to view performances from home, offers five key Digital Viewing Tips to enhance the at-home experience.