Nureyev Gala: Anticipating an occasion to remember

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Nureyev Gala: Anticipating an occasion to remember

By Gerard Davis

Rudolf Nureyev has become an almost mythological name in ballet. Probably best known for his 1961 defection to the West from the Soviet Union and for his partnership with Margot Fonteyn, he transformed the art form he loved through his dancing, choreography, and international stardom. If you asked anyone in the world to name just one ballet dancer it would most likely be Rudolf Nureyev.

But he died in 1993 and many of the people who knew him have also now passed on. What, then, does Nureyev mean to a new generation of dancers who only know of him through hearsay and YouTube videos? Quite a lot, it transpires. Take Nehemiah Kish, former principal dancer with the Royal Ballet, Royal Danish Ballet, and National Ballet of Canada. He’s so inspired by the man that, this September, he’s organized an extraordinary gala, Nureyev: Legend and Legacy, at London’s Theatre Royal Drury Lane, the same theatre where Nureyev made his London debut in 1961. (The gala will be filmed, available at www.marquee.tv on a pay-per-view basis, Sept. 16–26.)

Kish retired from dancing in 2019, and immediately undertook a postgraduate course in arts and cultural policy at Goldsmiths, University of London. While studying there, he hit upon the idea of the gala. “I was reflecting on my career,” he says, looking very calm in London’s Royal Academy library on our Zoom call, “and realized I’d worked with many people who had close connections to Nureyev, from the time I started school in Toronto, right through to the end of my career at the Royal Ballet. I was fascinated by the stories about him and loved learning about what, in many ways, I consider to be the golden era of ballet. I decided on the idea of a gala as a way to celebrate how Nureyev’s influence continues throughout the dance world today.”

He got in touch with Prudence Skene, a trustee with the Rudolf Nureyev Foundation (an organization set up by Nureyev in 1975 with the aim of, among other things, promoting ballet, dancers, and companies) and the idea quickly became a reality. Choosing to focus on Nureyev’s classical repertoire, a roll call of over 20 of the world’s finest dancers has been announced, including Alina Cojocaru, Guillaume Côté, Francesca Hayward, Oleg Ivenko, Germain Louvet, Maia Makhateli, Vadim Muntagirov, and Natalia Osipova, all of whom have indirect links to Nureyev through coaches, teachers, or financial awards from his foundation.

Another of those dancers is Cesar Corrales, the Cuban-Canadian principal dancer of the Royal Ballet and a former principal of English National Ballet, who trained at Canada’s National Ballet School. I speak to him via Zoom just minutes after he’s returned home from a performance in Italy. “I think Nureyev is an inspiration for every dancer, male or female,” the 25-year-old says. “There are fantastic videos of him on the internet where you can see how fast he moved his feet and how quickly he turned; it wasn’t necessarily the cleanest technique, but there was something special about him, he had an aura. I would compare him to somebody like [boxer] Muhammad Ali; neither of them were perfect but they did incredible things and they paved the way for the next generation.”

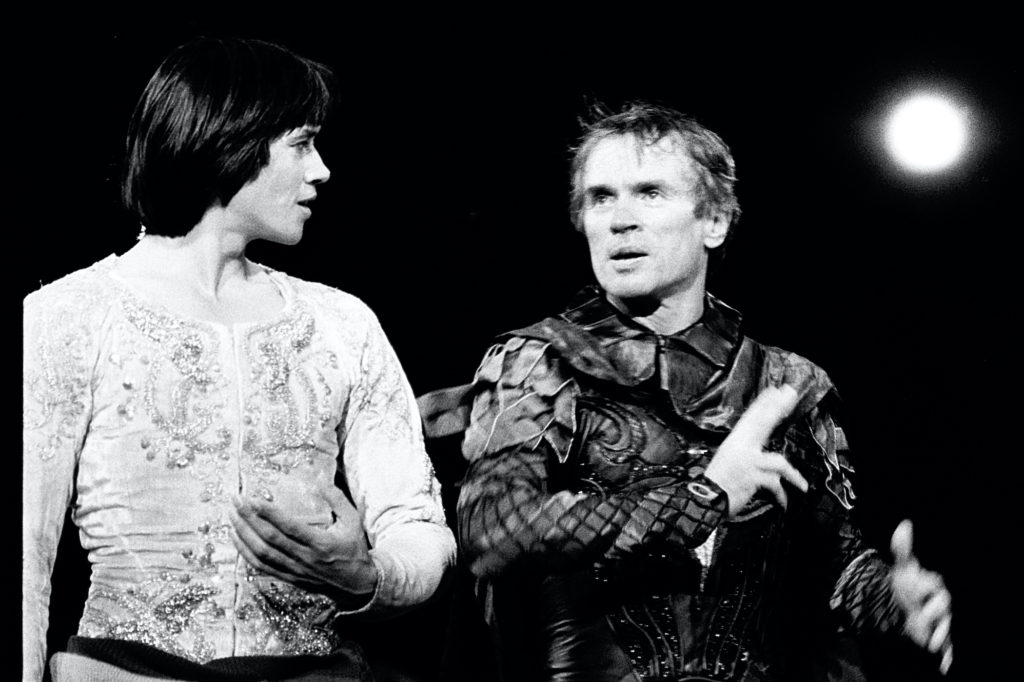

In his current workplace, the Royal Opera House in London, the ghost of Nureyev is everywhere. “Just before you enter the stage there’s a massive picture of him looking down. Sometimes we take it for granted to have that kind of history in the building, so the photo is a really good reminder.” He felt the same presence of history when he was with English National Ballet, when they were based in Markova House. “The conditions weren’t great there but working on Nureyev’s Romeo and Juliet, in the studio where he created it, was priceless.”

As a dancer, Corrales is known for his flamboyant style, something he shares with Nureyev, but it’s not simply the Russian’s pyrotechnics that impress him. “Although he was many levels above most dancers of his generation, the fact he went to Denmark and knocked on the door of Erik Bruhn because he still wanted to learn shows so much about his dedication to the art form,” he says, adding with a laugh, “Actually, what I’d really like to know is how he balanced that commitment with the party life, because I don’t know anyone today who can get it right!”

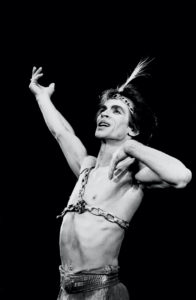

In the gala, Corrales is scheduled to dance the Le Corsaire pas de deux, which is one of Nureyev’s most celebrated roles. “It’s a privilege to be able to represent such a great name,” he enthuses. “It’s almost a duty you feel you owe Nureyev, to perform at your highest level and give the moment what it deserves, because it deserves the best.”

Kish considers Nureyev to be an important figure in the evolution of the male dancer. “He challenged us [technically] in order to put us on a par with the ballerina,” he says. For him, as a young male dancer growing up, “the most famous name in ballet was Rudolf Nureyev and his reputation was an encouragement to young boys to dance. He’s a symbol to many people, actually; the story of his birth on a train in Siberia showed that ballet dancers can come from anywhere and that the art form can transcend borders and nationalism.”

There are, of course, a huge number of stories that have grown up around Nureyev, some comic, some faintly scurrilous, and many that focus on his sometimes prickly personality. While acknowledging they are an important part of the Nureyev legend, Kish feels there’s another, often overlooked side to him. “While putting this program together I’ve been speaking to many people who knew Nureyev and a lot of these conversations have revealed his incredible generosity, especially to friends in need. I think that speaks volumes about the man.”

It seems then, that Nureyev is far from forgotten by today’s dancers. The impact he made and the changes he wrought are still being felt nearly 30 years after his death, and the appreciation for him and his achievements is palpable. As we wind up the interview, I ask Kish what he would ask Nureyev if he could meet him. He pauses thoughtfully for a few moments before gently saying, “I think I would just thank him.”