Behind the Scenes: At the Bayerisches Opera House Workshops

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Behind the Scenes: At the Bayerisches Opera House Workshops

By Jeannette Andersen

Munich’s Bayerisches Staatsballett recently offered a rare glimpse into some of the more practical details around putting a ballet on stage in a big opera house. Instead of their annual joint press conference with the opera at the theatre itself, they hosted a visit at the set building workshops located half-an-hour’s drive away.

There, in an industrial area surrounded by farmland, the sets for every ballet and opera production are created almost exclusively from scratch. Seventy-one full-time employees — carpenters, metalworkers, painters, interior- and stage-designers — and a number of apprentices occupy 10,000 square metres of work space.

In early October, I returned for an interview with Peter Buchheit, the head of the workshops, to get a behind-the-scenes story about the sets for a new ballet commissioned from Alexei Ratmansky, Tchaikovsky Overtures. Buchheit’s work was already well in motion, with the choreographer scheduled to arrive at the end of October, giving Ratmansky approximately nine weeks to work with the dancers before the premiere on December 23.

The set build had started in January 2022 after a long planning phase by Ratmansky, set designer Jean-Marc Puissant and Buchheit. Ratmansky and Puissant developed ideas, after which Puissant made some drawings and models that he brought to the workshop. Then, said Buchheit, “We discussed how to build them. Before we could do that, we had what we call a stage rehearsal, when the stage designer builds a model using cheap materials. We put this onstage to see if it works and if the proportions are right for the proscenium.”

At that point, Buchheit and Puissant discussed what material should be used for the actual set. Different types of canvas, with lighting, were tried out for the backdrops and side curtains in order to judge the effect. In this case, Puissant chose a sturdy canvas that would survive the moving, hanging, and storing.

After this introduction to the process, we went into the huge paint shop where Buchheit showed me a number of Puissant’s drawings, mostly watercolours. Some were very artistic, with blue colours spilling over the paper like errant streams. One looked like a finished model: on a beige-grey background, a bluish tree-like shape spread out, adorned with three wooden poles.

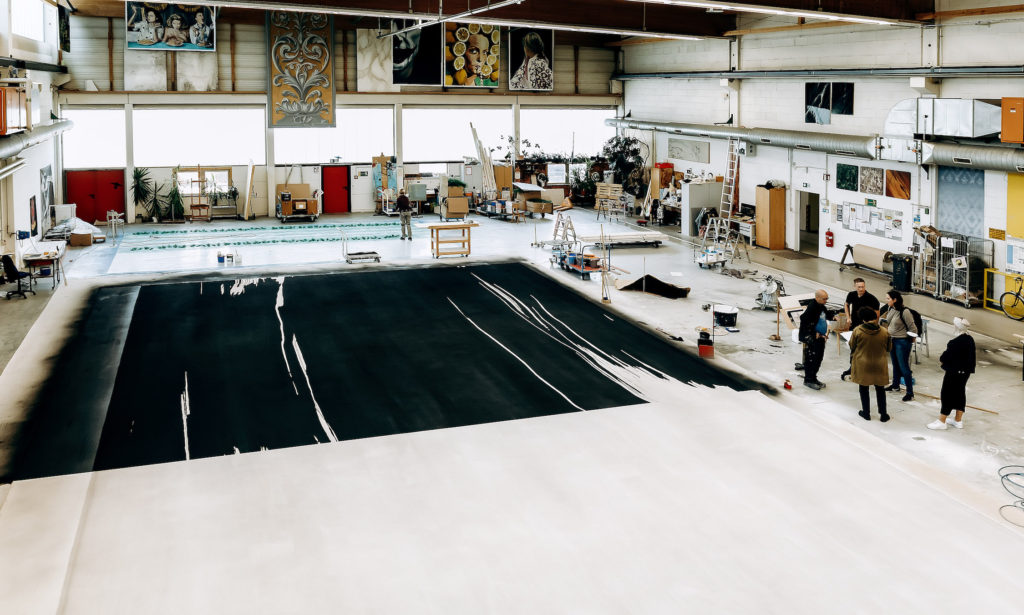

Some of the backdrops for the ballet were already finished, rolled up and stored away, ready to go to the theatre. But one large backdrop lay spread out on the floor. A woman was walking across it with a paint sprayer, while her colleague stood at the side holding up the tubes through which the paint flowed so they would not touch and ruin the canvas. Because the canvas is so big, the only way to paint it is to walk on it when the last layer of paint is dry.

“To achieve the right colour,” said Buchheit, “it took ten layers of paint and each had to dry before we could apply the next. This process took 10 days. For the first prime coat we needed eight people applying the paint simultaneously; if it dries out in places during this process, you will see a patchy effect from the auditorium.”

If Puissant had chosen a backdrop with a painted floral pattern, two to three painters would have been required. The canvas would be divided into panels, with each painter tackling non-consecutive parts in order to ensure that their inevitably different styles would not stand out and be visible to the audience.

Wooden poles and some brass ornaments that will later be applied to the backdrop were not available for viewing, so we proceeded into the assembly hangar, which has a huge loading bay. Here they drive in the containers used for storage and transport to the theatre.

On our way we passed by some small bush-like trees with leaves made out of metal. They are part of the glittering magic wood in John Neumeier’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which the company was preparing to perform. The ballet has been in the repertoire for almost 30 years and the sets are as old. Last season someone discovered sharp protruding spikes, which could hurt the dancers, so they were being repaired before the ballet got back on stage this season. Repairs are part of Buchheit’s job. “We try to make everything as stable as possible,” he explains, “but the stage is a rough environment and repairs are part of the ‘repertoire.’”

In the assembly hangar, the sets are checked by the interior decorators and sculptors (model-makers) before they leave the workshops. The ceiling is not high enough to hang them, so they are laid on the floor. Then they are cut into pieces to fit into the containers in which they are transported to the theatre and later on stored. The containers are 9.50 metres long, 2.50 metres high, and 2.15 metres wide. They cannot be bigger because they have to fit through the doors to the stage at the theatre.

Buchheit estimates that around five containers will be needed for Ratmansky’s ballet. The sets only consist of three to four backdrops, side curtains, side legs, wings, and the dance floor. The ballet in the repertoire with the largest set is Christopher Wheeldon’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which had its company premiere in 2017. It takes up around 12 containers because it consists of so many objects and large volume pieces, including the cat, the finger, the items making up the pigs’ kitchen, and the large hand which descends from above.

Wheeldon’s Cinderella, in the repertoire since 2021, was originally a co-production between San Francisco Ballet and Dutch National Ballet. I wondered if Bayerisches Staatsballett could not have borrowed the sets from one of these companies, instead of making their own. Says Buchheit, “It is difficult, because every stage is different. Ours is, I think, the fifth largest in Europe and the largest in Germany, so the sets from many other theatres would be too small.”

The departments for props, costumes, and shoes are located at the opera house; the latter two mean the dancers can go directly from training or rehearsals to their fittings. As for furniture, Buchheit says, “If we need some pieces, we either find them in our storage, buy them, or we have to build them, as was the case for the bed in John Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet, which the company dances at the moment.” The bed had to be tilted so the audience can see the action that takes place on it, and the mattress had to be hard so the dancers do not sink into it.

The company has about 40 ballets in the repertoire. The sets for these and all the operas take up 750 containers. Two hundred are in rented storage space, 450 are on the premises in a computer operated high-rack storage house. The containers are taken out of the trucks that bring them to and from the theatre and loaded into storage in an efficient automated process. A building site visible through the opening of the loading bay will eventually become the new storage house, which will have space for 900 containers.

“Sustainability is, of course, important. Sets for ballets which are no longer in the repertoire are disposed of, though we keep everything that we can use again. The rest we try to pass on to other theatres, but for most stages our sets are too big,” says Buchheit.

Fire is an ongoing concern. Almost all materials have to be fire resistant. If something with fire or smoke is going to be onstage, it must be justified dramaturgically, and then extra measures are taken during the performance; for example, wet cloths lie ready or extra flaps have to be built that can be closed by hand in order to cut off the oxygen supply in case of a fire.

The stage also has an automatic fire-extinguishing system, which reacts to smoke and heat. Water will flood the stage, inevitably ruining the electrical equipment and the floor. Buchheit, who started at the workshops in 2009 as a design engineer, becoming head of the workshops in 2017, says: “Luckily, I have never had that experience.”

At every performance, six firefighters are backstage with extinguishing equipment. “When we have a lot of fog, like in A Midsummer Night’s Dream playing this season, we have to inform the firefighters so they can deactivate the part of the system that would react to smoke. The dancers are not allowed onstage before the firefighters have inspected and approved of the sets and have been informed about everything that could cause a fire.”

With a smile, Buchheit adds, “And for the dancers’ extra safety, we have a physiotherapist in the wings, and a doctor and paramedic sitting in the auditorium.”