Vancouver: A rare Ballet BC duet, an hour with Lecavalier and other highlights

- Home

- City Reports 2020 - 2023

- Vancouver: A rare Ballet BC duet, an hour with Lecavalier and other highlights

By Kaija Pepper

The title of Jeanette Kotowich’s Kisiskâciwan comes from the Cree word for “swift-flowing river,” kisiskâciwanisîpiy, which became Saskatchewan — the prairie province where she grew up. In this choreographic memoir, Kotowich (now based in Vancouver) looks back to her childhood, evoking the gently rolling land’s geographical contours in a series of still — or very slowly moving — lifes. In a more dynamic scene, she becomes a prancing, whinnying horse, magically morphing into a flirtatious party girl, jigging and kicking up her heels to some verses from Buffalo Gals Won’t You Come Out Tonight? Kotowich is a longtime dancer with a Métis group, V’ni Dansi, and this scene showcased her dancing chops as well as as a daring spirit of dramatic exploration, creating something that was uniquely subtle and playful.

Kotowich, who is of Cree, Métis, German, Polish, and Scottish heritage, opened Kisiskâciwan at Vancouver’s Dance Centre on September 30, Canada’s second National Day for Truth and Reconciliation — a federal holiday intended to honour the Indigenous children who suffered through the notorious residential school system. Kisiskâciwan seemed to offer a statement of healing and even joy: it began with the lively fiddle-playing of Kathleen Nisbet, resplendent in sparkly red cowboy boots, and ended with Kotowich roaming through the audience hugging friends and enticing them onstage to dance.

Ballet BC’s November home season opener at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre was a lively triple bill with, at its centre, a rare duet, a welcome opportunity to see company dancers in action for a more sustained view. Silent Tides, created by artistic director Medhi Walerski for Nederlands Dans Theater in 2020, featured an opening night cast of Sarah Pippin and Rae Srivastava, both in white pants and socks, both bare-breasted, which, for the woman, added a certain vulnerability. Yet she blazed through the slow, measured moves, at times reminiscent of a tai chi flow but unfolding much more luxuriously. Pippin’s pliant back, and the gracefully unfolding arc of her split-open legs as she tumbled over Srivastava’s body, were a lyrical feast. Well-lit, with a single bar of fluorescent light upstage to define the space, Silent Tides unfolded with quiet presence through the gentle connection between partners.

The evening’s world premiere, Heart Drive, by Dutch siblings Imre and Marne van Opstal, featured eight dancers in black latex leotards, bare-legged, crashing through their moves: crawling, bums up; lying face down on the stage, flopping their lower bodies like dying fish; hunkering down in low second position pliés. The striking set, by lighting designer Tom Visser and the van Opstals, was a changing array of massive geometrical shapes magically constructed through lighting and projection, while a loud, constantly changing score by Amos Ben-Tal provided a driving beat. Heart Drive had the same vaguely ominous runway cool of the opening Bedroom Folk, by Israeli team Sharon Eyal and Gai Behar, premiered by NDT in 2015 and in Ballet BC’s repertoire since 2019.

Ballet BC’s roster of 20 dancers includes, this season, 13 from the United States, with just four Canadians (there are two Europeans and one Argentinean as well). Most companies today have an international line-up, but, in our always fragile Canadian cultural scene — it’s hard making our own impact next to the powerful neighbour to the south — the numbers seem important to note.

Corporeal Imago, founded in 2018 and still a newcomer to the Vancouver scene, is run by Gabrielle Martin and Jeremiah Hughes, who both have respected pedigrees as former Cirque du Soleil performers. There’s a particular buzz around Martin, who is the director of programming at the high-profile PuSh International Performing Arts Festival.

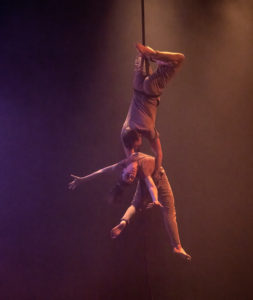

Their co-created Throe, at Scotiabank Dance Centre November 17-19, was a subdued exploration for six dancers (including Hughes) of what the program note describes as “bodies in the throes of survival.” Clad in workaday boiler suits, half-hidden by intense fog, the group’s slow, effortful movement on the ground contrasted with a sense of release and abandon in aerial work on three ropes. Above ground, there were some inventive couplings of ropes and nimble dancers. Sophie Tang’s use of orange or red lights to cut through the fog provided fleeting bursts of spooky illumination.

Ne.Sans Opera and Dance’s artistic director, Idan Cohen, presented his Hourglass, a life narrative over two acts that featured the major draw of Leslie Dala onstage playing Philip Glass’ complete set of Piano Études. Unfortunately, the live music experience was somewhat marred by the constant shushing sound of the dancers sliding on a strangely noisy wood-effect overlay covering the stage floor.

The show was part of Chutzpah! Festival, at the Norman Rothstein Theatre throughout November, as was Alexis Fletcher and Arash Khakpour’s duet, همه هستی من آیه تاریکیست | All my being is a dark verse. The title is the first line in Reborn, a poem by Persian Forugh Farrokhzad. Premiering a work inspired by Farrokhzad’s poetry is “special… during calls for freedom from Iranians and women in the world,” as Fletcher and Khakpour (who is originally from Tehran) wrote in their program note. Both celebrated and castigated for her sensual poetry, Farrokhzad died at age 32 in 1967.

To end, a wonderful hour with Louise Lecavalier, part of the DanceHouse season, in her 2020 solo Stations. Lecavalier’s presence has been iconic in the world’s contemporary dance scene from her early days as La La La Human Steps’ star risk-taker; now a soloist in her 60s, the Montreal artist is as singular and striking as ever.

Onstage at the Fei and Milton Wong Experimental Theatre at the end of November, Lecavalier pursued her agenda with seemingly easy rigour, almost without stop, as if motion alone is what keeps her alive. Perhaps it is, as she laid claim to every inch of the large stage space, which was ethereally defined by four fluorescent tubes standing at the corners and the vibrant colour palette of lighting designer Alain Lortie. Lecavalier shared a more intimate space with us, too — that of her own small frame, constantly touching and exploring her body and how it can balance and stretch, how it can go this far and no further, all with the forthright muscular grace and power for which she has long been celebrated.