John Cranko, Storyteller: Romeo & Juliet, and other resonant master ballets

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- John Cranko, Storyteller: Romeo & Juliet, and other resonant master ballets

By Ashley Killar

When Australian Ballet revived John Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet at the end of last year, it looked fresh as paint, though it was 20 years since they had last danced the ballet. I saw the December 1 performance in Sydney — and the next morning realized that December 2 was the 60th anniversary of the world premiere of Cranko’s Romeo and Juliet in Stuttgart … a production I had danced in as a very green new recruit from London’s Royal Ballet School.

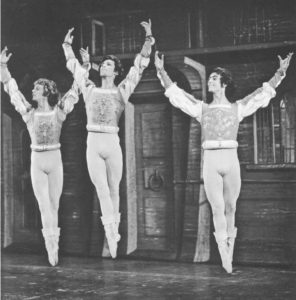

Romeo and Juliet was Cranko’s first triumph as Stuttgart Ballet’s director. Previously, as resident choreographer at the Royal Ballet, he was well known for his witty Pineapple Poll and The Lady and the Fool, but a string of later ballets — with subjects as diverse as Greek heroine Antigone and murderous barber Sweeney Todd — did not meet much acclaim. Having seen the Bolshoi’s version of Romeo and Juliet in London and Frederick Ashton’s very different one in Copenhagen, Cranko decided to mount his own when invited to choreograph for the ballet company of La Scala, Milan. His production premiered with Carla Fracci as Juliet, and the company performed it initially on an island resort where there were few facilities for scene changes. The ballet requires at least seven changes of location, so Cranko invented a set built as a double-storey gallery whose structure could be quickly transformed from town square, to rich formal interior, to Juliet’s bedchamber, its balcony or her tomb. When Cranko mounted the now-famous Stuttgart version, he and designer Jürgen Rose retained the idea of the fixed set, since copied in countless other versions of the ballet.

Sergei Prokofiev’s music is both highly theatrical and psychologically penetrating; the same applies to Cranko’s production. Not only are Juliet, Romeo, Mercutio, and their friends sharply etched in music and dance, but the non-dancing characters contribute to the relentless pace that Cranko’s ballet shares with Shakespeare’s text. Nothing flags for a moment, and this struck me yet again at Australian Ballet’s performance.

In 1965, I was fortunate enough to be in the Stuttgart premiere of Onegin, another of Cranko’s much loved ballets. Marcia Haydée, his muse in Stuttgart, was the first Tatiana. He usually worked incredibly quickly, and liked to leave what he called his “messes” so he could push on. But with Onegin it was different, as if he knew he had a masterpiece on his hands. The ballet evolved relatively slowly, with revisions continuing over a number of years. Only the pas de deux for Olga and Lensky, and Tatiana’s with Onegin and Gremin, remained unaltered. The peasants’ dances in Act 1 had at least five versions during Cranko’s lifetime.

Now that Onegin has attained classic status, the major roles are coveted by any number of leading dancers around the world. The story has universal appeal, and Cranko was one of the greatest storytellers. Imagine trying to transmute the convoluted plot and tangle of relationships of a complicated play into an instantly enjoyable ballet! Well, he did that in The Taming of the Shrew. There aren’t many full-length narrative ballets that contain numerous truly witty passages — and this one must head the list.

Cranko often gave the subjects of his ballets a forceful message: in Taming of the Shrew, he freed the ballerina from what was then an unremitting image of perpetual virginity. And in many of his ballets — The Lady and the Fool, Beauty and the Beast, and The Prince of the Pagodas spring to mind — his favourite themes of masks and identity recur time and time again. Anguish often lies just beneath the surface of these highly entertaining ballets. Cranko possessed a similar dualism in his temperament. He was gregarious and loved to participate in Greek dancing at a local taverna, to travel widely and meet new people, yet he was one of the loneliest men I have ever known. As his administrator colleague Dieter Gräfe said, “He was always looking for love. He was always looking, looking, looking. And he never found it.”

Despite a period of great depression, Cranko produced some extraordinary work toward the end of his short life. There was Poème de l’Extase for Margot Fonteyn, in which a diva remembers her former lovers amidst billowing cloaks and Klimt-inspired decor. Then came a tribute, a kind of token of love for the four leading dancers of his company, Richard Cragun, Birgit Keil, Marcia Haydée, and Egon Madsen; he called it Initials R.B.M.E. Finally, there was Traces, a haunting piece of dance theatre set to searing music by Mahler.

The New York Times called Cranko’s company “The Stuttgart Ballet Miracle.” Taking the dancers on a third, wildly successful tour of the United States in 1973, Cranko was full of plans for new ballets. Tragically, he never had a chance to achieve them: he choked to death during the return flight while mid-Atlantic. He was only 45.

Who knows how Cranko’s choreography might have progressed? I am sure that film and multimedia would have played a large part. But, of the 80 ballets he choreographed, those that survive form a rich heritage.

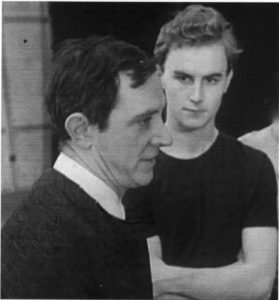

Studying Cranko’s writings and stage works closely while researching Cranko: The Man and His Choreography — the book I recently published — one conclusion I came to was that he was unusually perceptive about body language. He was also tremendously human and empathetic in spirit. All this was at the root of his unique ability to translate the emotions of his characters into dramatically satisfying dance.