By Kristen Lawson

Betsy Wetzig has been interested in patterns of movement since she was very young. She began studying with Estelle Dennis in Baltimore at the age of 6, joining her dance company as their youngest member at 11, and creating her first choreography for them at 16. During this time, Dennis brought in guest artists like George Balanchine, Margot Fonteyn, and former Ballets Russes dancers. Watching them, Wetzig noticed an intriguing phenomenon that would fascinate her for years to come. “You had these incredible athletes, artists who could do extraordinary things in one style, but couldn’t in another. It wasn’t just training, it was their nature, and I wanted to know what it was.”

In 1971, while teaching improvisation at the American Dance Festival, she learned of neuromuscular tension patterns and the corresponding tension scale, which describes the different firing orders of nerves acting on muscles. Inspired, she immediately began testing friends and colleagues at the festival to find their “lowest tension neuromuscular pattern,” or home pattern. This is the pattern that comes most naturally to a person, that they feel the most comfortable using. Home patterns begin to develop in infancy, and are further informed by training and culture.

In this way she identified four states of being to which different dancers gravitate, naming them Thrust, Shape, Swing, and Hang. These patterns form the basis of Wetzig’s Coordination Pattern Training, which she teaches across Canada and the United States. Coordination patterns describe different neuromuscular sequences which can appear in every kind of movement, including breathing, walking, and engaging in fine motor skills. Everyone uses some combination of all four patterns, with one or two dominant ones. Wetzig developed her training exercises to help dancers move in a more efficient and balanced way using the patterns and their respective centres of movement.

Thrust describes the muscular pattern used for powerful, often asymmetrical movements that start just above the pubic bone. This driving energy is often used in Graham technique. While compelling, overuse of the thrust pattern can cause increased tension in the hips and occipital muscles, resulting in headaches and burnout.

Shape is the pattern often seen in ballet and yoga, prioritizing symmetry and balance. Its qualities include focus and clarity, which are necessary for performing precise, controlled movement. The centre of movement is at the diaphragm, meaning overuse can cause tightness in the ribs and joints, leading to problems jumping and breathing.

Swing, originating from the navel, is associated with collaboration and play. Swing movers are often influenced by mental imagery, using their sense of play to embellish movements and engage with other people. This pattern is group-oriented, perfect for improvisation. The drawback is a tendency to get distracted and go off task.

Hang is the dominant pattern used by Isadora Duncan (and Wetzig herself). It supports a style of dance that is effortless and spontaneous, with the centre of movement constantly changing. This pattern is associated with going with the flow and taking risks. The indirect nature of it can seem chaotic, as the dancer focuses on the whole and can lose track of details.

Wetzig has worked with students of all ages throughout her career. When teaching movement and dance courses at the post-secondary level, Wetzig prepared her students to perform various choreographic styles by leading them in pattern-based movement exercises that put them in specific mind-body states. They might use thrust coordination exercises before performing a Graham work, then return to the wings and practice shape-based exercises in anticipation of a balletic piece.

With preschool and elementary age children, Wetzig noted that generally the youngest are allowed to dance freestyle, doing what makes them happy. She has seen many children become discouraged once a more rigid style is imposed. A child with a swing home pattern might think they can’t dance if they struggle with shape-based ballet.

Engaging in a variety of styles and exercises can help dancers discover their strengths and address their weaknesses. For example, Wetzig was taking Martha Graham’s classes in the late 1960s, immersed in the thrust pattern, when she started sitting in on Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater rehearsals. “Ailey has a lot of hang, so it was a really important piece of my development,” she realizes now, adding: “Another piece of dance history, dance understanding, and dance enjoyment is seeing the beauty of the different styles.”

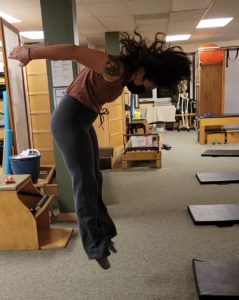

I recently took one of Wetzig’s workshops at the Vancouver Pilates Centre, the second in her three-part series Release, Re-pattern, and Renew. She had us repeat every exercise in each pattern. We might start with a crescent roll in thrust, then transition to shape, hang, and swing in turn. Each pattern added a different element to the movement, turning it into something else completely. Personally I struggled with thrust, preferring to take my time and let my movement wander. Knowing this can help me find the neuromuscular patterns I need to effectively execute my usual Pilates exercises.

Learning coordination patterns makes a dancer more versatile, allowing them to understand different ways of moving and being. They can enrich the study of specific techniques, prevent stress injuries, and allow a dancer to explore their personal style of expression.