Sharing Parts+Labour: At home and in the studio

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Sharing Parts+Labour: At home and in the studio

By Philip Szporer

As partners in life and work, Emily Gualtieri and David Albert-Toth, co-artistic directors of Montreal’s Parts+Labour_Danse, are on the move. Quite literally. They recently bought their first condo in the Verdun borough, a world away from their friends and colleagues across town, which houses their private living space, and also the company office. They may be new to the recently gentrified residential area, but this gregarious duo, with dog Mila in tow, are finding their way.

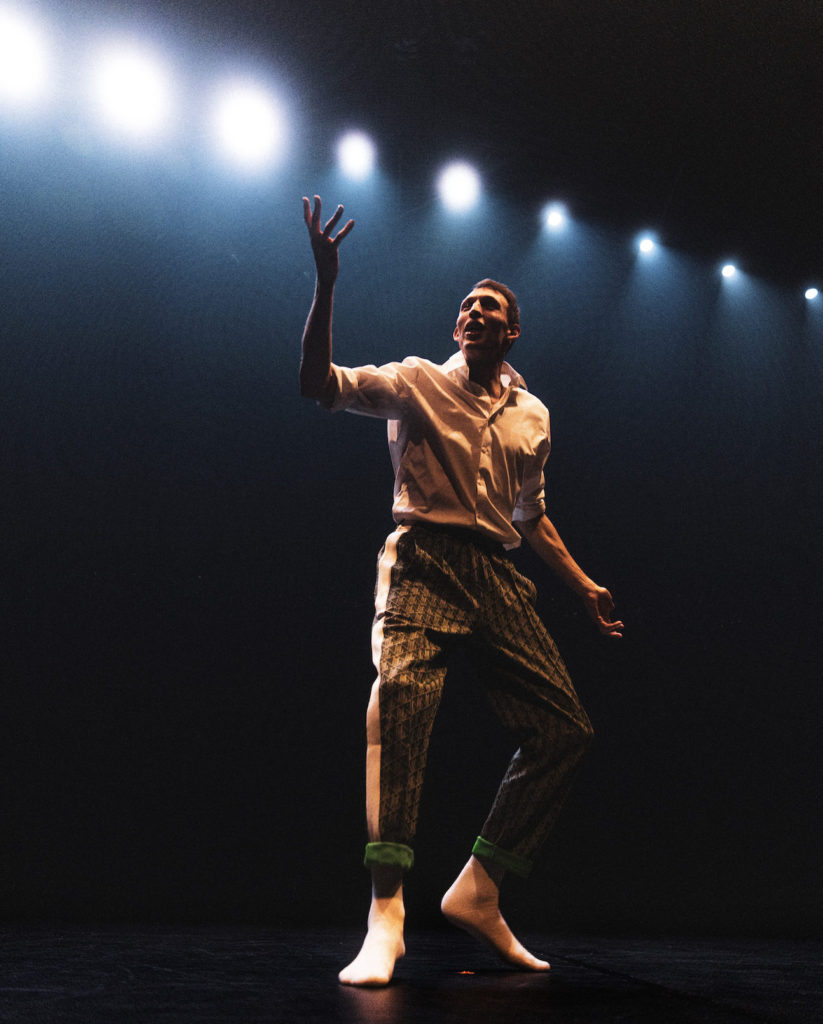

This summer, Parts+Labour is making inroads with audiences, too, premiering new work outside the city at the Festival des arts de St-Sauveur on August 4-5, with a site-specific duet, One More for Good Measure, with a forest as backdrop. Across the country at Vancouver’s Dancing on the Edge festival on July 8-9, the company will present À bout de bras, a solo featuring Albert-Toth.

The newly engaged couple met as students at Concordia University’s Contemporary Dance department back in the early aughts. It was not love at first sight. “He didn’t like that I was from Toronto, and I didn’t like that he was untrained,” Gualtieri laughs. She was 19; Albert-Toth, the staunch Montrealer, was 20. She had lots of dance experience, he not so much. But they got to know each other and developed a deep mutual respect. “I was in awe of the huge talent there in the room, and the wildness of her spirit,” he says. Gualtieri saw Albert-Toth had a raw, comedic sense, adding: “His potential was untapped.” As students, they danced in each other’s works, and bonded over their avid love for dance.

Gualtieri started dancing at age five. “In grade five or six, it looked like I was being primed,” she says. But once puberty hit, she was told she didn’t have the right body type by her ballet teacher at the National Ballet School, which “was harsh and heart-breaking” to hear. Yet, in that moment, Gualtieri was also thankful. “I said to myself, this is it. These are the options. I wasn’t going to change my body.” Subsequently, she was out of the program, acting in some plays, indie films, and commercials. Still, dance was closest to her heart.

Albert-Toth’s backstory begins when, as a teenager, he fell in love with hip hop, club culture, and rave culture. Wanting to take his passion to the next level, he auditioned at Concordia and was accepted, as was Gualtieri. The department’s focus on students creating their own pieces sold them, and, for Gualtieri, there was much more acceptance of different types of bodies.

After several years spent dancing and choreographing independently, Gualtieri and Albert-Toth began a creative partnership more concretely, founding Parts+Labour in 2011. The duo often co-create, building intelligent, physical contemporary work that leans into human experience. In the quartet In Mixed Company (2013), they drew on Eugene Ionesco and Milan Kundera’s concerns with the absurdity of the modern human condition, while La vie attend (2017), for five men, was cited by Le Devoir’s Catherine Lalonde for its “highly elastic, sensual gestures of waiting, sequential movements [that] create large kinespheres around the five performers.”

With La vie attend, Albert-Toth really wanted to make a group work, and while Gualtieri was on board, the deal was that she really wanted to eventually make a solo on him, and that’s how the creative impulse flows. “After every show, we ask what’s working or not, and what do we each need creatively,” she says. Defining their roles demands a constant questioning. “It gives us more reason to stay together,” she says.

The group work Efer (2021), created during the pandemic, tackles themes of grief, mourning, and renewal (the title means “ashes” in Hebrew), while À bout de bras (2022), a solo for Albert-Toth, co-created by him and Gualtieri, with text by writer and dramaturge Étienne Lepage, builds on humankind’s push-pull relationship with solitude.

Their partnership draws on their strengths. “I’m a workhorse. Emily brings the inspiration. She’s able to tap into something bigger than herself in a way that I can’t,” says Albert-Toth, who’s also the company general manager. That quality gives her the capacity to be critical, he suggests, and yet Gualtieri’s warmth provides a safe space for artists to thrive, and collaborators love working with her. “You can feel that in the room.”

The duo say their larger team, comprising dancers, writers, set designers, and filmmakers, has a vocal role in creation of the work. Over the years, a substantial next-generation cohort, including composer Antoine Berthiaume, choreographer Mélanie Demers (working as an outside eye), designer Paul Chambers, and filmmaker Robin Pineda Gould, have participated in their process.

In Gualtieri’s eyes, Albert-Toth’s enthusiasm drives the work, and helps to create a healthy environment. He’s also one of the city’s go-to interprètes, working with Frédérick Gravel, among others. Gualtieri has not danced for almost 15 years. “I felt we didn’t need more good dancers, we needed more good leaders. It was important for me to head that change. The backlash was that I lost my own practice” — which, she says, she’s just starting up again.

Dance takes precedence in the relationship. As collaborators, “the work is never compromised. We have a strong professional relationship,” says Gualtieri. One all-consuming challenge is working all the time, they admit. Dancers can arguably clock out, but as creators there are grants to write, administrative tasks, and the creative stresses about whether your ideas are any good. “It makes me feel less lonely being with someone,” Albert-Toth affirms.

They may problem-solve differently, but “the creative process isn’t just problems, it’s also magic,” says Gualtieri. “You bring all of that home with you, too.”