Sydney Celebrations and an Australian Classic Novel Onstage in Brisbane

- Home

- City Reports 2020 - 2023

- Sydney Celebrations and an Australian Classic Novel Onstage in Brisbane

By Deborah Jones

Rafael Bonachela has been artistic director of Sydney Dance Company for 14 years and recently signed for another five. He’s still as bright-eyed as when he started, and, as a choreographer, always exploring collaborations with other artists and generous about bringing in guest dancemakers.

The March triple bill Ascent introduced the company to Spanish choreographer Marina Mascarell and brought back Australian Antony Hamilton’s 2018 smash hit Forever & Ever, giving it pride of place as the evening’s closer. Well, it’s such a show-stopper anything else would have been perverse.

Bonachela’s modestly scaled, ponderously titled I Am-ness opened the evening with light, music, and four dancers in quiet harmony for just 15 minutes. Damien Cooper’s dreamily hazy light filled the space, as did the calm beauty of Lonely Angel, a meditation for strings by Pēteris Vasks. It was inspired by a vision of an angel looking at Earth with fear but offering comfort and healing with what Vasks called an “almost imperceptible, loving touch of his wings.” Bonachela put aside fear and went for the loving touch as bodies glided and floated around one another, rarely separating and, yes, offering comfort.

Mascarell also came up with an unwieldy title. The Shell, A Ghost, The Host & The Lyrebird didn’t give up its intentions lightly but there was a strong sense of humanity needing to come to grips with an alien environment. Seven dancers pulled on ropes and manipulated huge hanging cloths, bringing to mind sailors on an ancient ship, campers in the wilderness, or perhaps explorers on a distant, barren planet. The commissioned score by Nick Wales beautifully evoked both natural and constructed worlds and the dancers’ deep concentration was catching. Their sense of needing to find shelter, discover purpose, and survive was ultimately moving.

The Australian Ballet’s 60th anniversary — it was born on November 2, 1962 — is being celebrated right through 2023 with a mix of old and new. Warhorse Don Quixote, the company premiere of Jewels, and the contemporary double bill Identity took up the first half of the year with performances in Sydney as well as the company’s home base of Melbourne. The Australian Ballet is on the move regularly, usually getting to a third capital city as well as the big two.

Rudolf Nureyev’s Don Quixote in April was given extra zest with new sets and costumes based on those in the widely seen 1973 film version. There were even movie-style credits to mask the set change between the prologue and Act I. Don Q was studded with happy, zingy performances from the three casts I saw.

Principal artists Brett Chynoweth and Ako Kondo were possibly the season’s most valuable players. They lit up Don Q with other partners and were paired in Jewels to show two more facets, if you’ll forgive me, of their artistry. They were an immaculate principal couple in Diamonds and brought the house down in Rubies. I’ve not seen better anywhere. The two had wit, sexiness, speed, razor-sharp attack, and an over-arching sense of ease and fun. The technical challenges were also smashed by gloriously tall soloist Isobel Dashwood, who looked a touch overawed at Sydney’s May opening, then, some weeks later when I saw her in Melbourne, rocked the room.

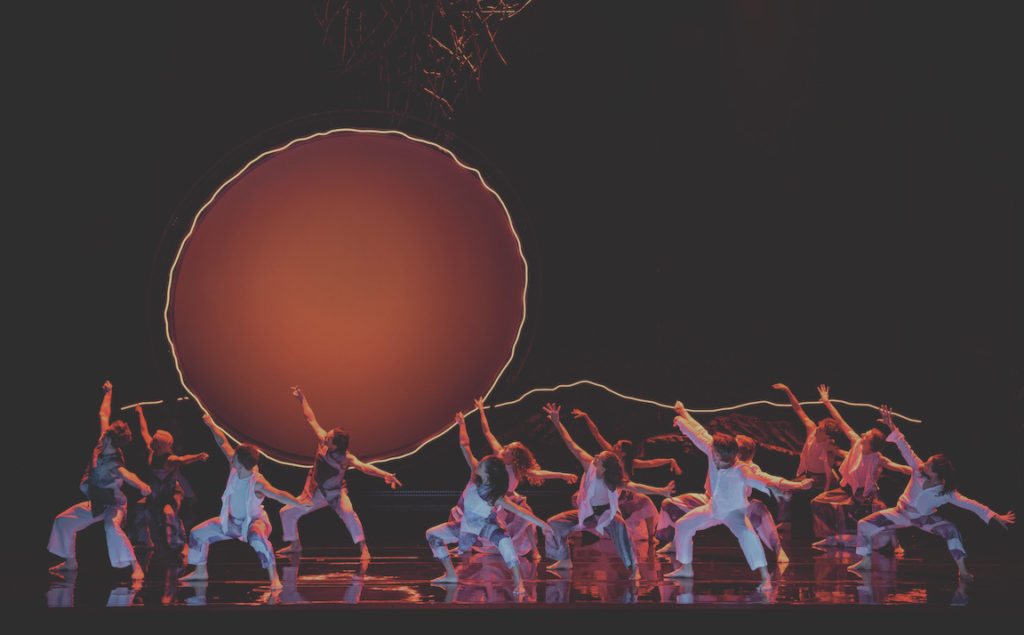

Identity was one for the home crowd. The first work, Daniel Riley’s THE HUM, had what sounds an elusive concept, that of belonging and sharing. In practice, it lived those principles. Riley’s own company, Australian Dance Theatre, joined Australian Ballet onstage for an abstract piece that drew on the combined energies of place, movement, music, design, light, and the audience’s presence.

For Identity’s second half, Paragon, Australian Ballet’s resident choreographer Alice Topp coaxed a dozen dazzling alumni from retirement to join today’s dancers in a living scrapbook of memories. Paragon was over-busy, but there was pleasure in rediscovering artists and images from the company’s past. The women alumni in particular radiated the wisdom of years but were seemingly ageless in the luscious quality of their movement.

Bangarra Dance Theatre has always lived and breathed the astonishingly long history of this island continent. In June, new artistic director Frances Rings continued the great work with Yuldea. The setting took the audience beyond the arid Nullarbor Plain in Australia’s south to that most precious of places, a waterhole that nurtured every aspect of First Nations life until colonists sucked it dry.

Yuldea looked stunning and the choreography had a powerful contemporary edge that nevertheless incorporated traditional shapes with ease. In a vast cycle of creation, destruction, and renewal a star exploded, spirits led the way to water, British atomic tests at Maralinga brought black rain, and First Nations people were shunted into missions. Rings declined to end Yuldea on this dark note, letting light and optimism prevail.

And now a brief detour to Brisbane, 730 km to the north of Sydney and not much more than an hour away by air. Here, in June, British choreographer Cathy Marston adapted the beloved 1901 Australian novel My Brilliant Career for Queensland Ballet.

Author Miles Franklin — full name Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin — wrote My Brilliant Career in the white heat of the emerging feminist movement in Australia, chafing against conventions, restrictions, and expectations. Clever, rebellious heroine Sybylla Melvyn has aspirations to greatness but lives in a rural world too small for her ambitions. Given the chance to marry well, she chooses her freedom.

Franklin’s Sybylla is passionate and unflinchingly direct, qualities softened by Marston. She split Sybylla in two to represent her undeniable contradictions, but Sybylla’s scratchy vigour wasn’t strengthened by being doubled; it was diluted. The ballet fell between two stools, neither pure abstraction nor fully fleshed narrative. The unusual 45-minute length — the work closed a triple bill — was telling. The piece was either too long or too short. It ended up being about a girl in two minds who knocked back a boy who loved her. The fierce young woman of the novel was made of more remarkable stuff.