An Evolving Story: From Singapore Dance Theatre to Singapore Ballet

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- An Evolving Story: From Singapore Dance Theatre to Singapore Ballet

By Malcolm Tay

Minutes before opening night of a special all-Choo-San Goh program on December 10, 2021, Singapore Dance Theatre made a major announcement: it would now be known as Singapore Ballet. To veteran spectators familiar with the company’s development, this was likely a welcome move that had been a long time coming.

Discussions with board members about the name shift had begun two years earlier. “The deciding factor was knowing that if the company was founded today with the ballets we do right now, we would not call it Singapore Dance Theatre,” says Janek Schergen, the Swedish-American who has been artistic director since 2008. “Evening-length productions such as Swan Lake and The Sleeping Beauty do not fit dance theatre as a concept.”

The renaming was motivated, too, by a recommendation from the National Arts Council, the country’s arts-development government agency, for local groups to “internationalize as much as possible.” With the current repertoire, Schergen believes that touring as Singapore Dance Theatre would be “a little bit of a misnomer,” but, as Singapore Ballet, “the expectation will be a lot clearer for an outside audience.”

The new name sounded “slightly odd at first,” says soloist Elaine Heng, a Singaporean who has been involved with the troupe since she was a young student. “But I’m used to it now. I feel the new name carries a bit more weight and plays to our advantage.”

Schergen says that this rebranding does not erase the achievements of Singapore Dance Theatre. The original name reflected an aim to explore a variety of styles beyond ballet. The troupe’s early repertoire included pieces by contemporary choreographers from the Asia-Pacific region, such as New Zealand native Timothy Gordon and Hong Kong stalwart Helen Lai, alongside works by founding co-artistic directors Soo Khim Goh (sister of Choo-San) and Anthony Then. It would later even embrace the dark theatricality of Japanese director-choreographer Sakiko Oshima, who had the performers dangling from cables.

In 1992, Then staged The Nutcracker for the company. The success of this venture led to acquiring other story-ballet staples — Coppélia in 1995, Giselle in 1999 — which have since comprised a third of the troupe’s annual programming. Today, every year is bookended with a multi-act classical production at the almost 2,000-seat Esplanade Theatre, where a triple-bill season takes place as well. There are also regular offerings of contemporary creations by foreign and local artists; outdoor shows on the lawn of Fort Canning Park, a hilltop historical site near the civic district; and sprightly ballets for children.

Prior to the inception of Singapore Dance Theatre, Singaporeans keen on pursuing ballet professionally had to go abroad for training and jobs (among them were Patricia Hon, who studied with Rosella Hightower in France and performed in Europe, and Kee Juan Han, an Australian Ballet School graduate who became a soloist at Boston Ballet). The troupe’s inaugural co-directors wanted not only to present world-class dance, but also to allow Singaporean dancers to have careers at home.

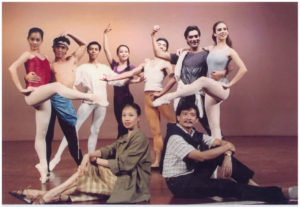

Singapore Dance Theatre debuted at the Singapore Festival of Arts in 1988, with three dancers from Singapore, one from Malaysia, and three from the Philippines. Now, 10 of the company’s 38 performers are Singaporean — the most so far. Compared to just one Singaporean in 2009, three in 2011, and five in 2014, this is a notable increase, despite the nation’s persistent lack of infrastructure to groom proficient ballet dancers.

Looking ahead, in June 2024 Singapore Ballet will travel to Salt Lake City for Ballet West’s Choreographic Festival. It will also appear at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, for the festival 10,000 Dreams: A Celebration of Asian Choreography, where it will present Choo-San Goh’s Configurations.

Although Configurations had not been seen in more than two decades, this drought was quenched in July when it was mounted at home for a triple bill marking the troupe’s 35th anniversary. The Singapore-born Goh was a key inspiration for the company’s formation and, for its inaugural concert, he had offered his 1983 quartet Beginnings. That the company could now perform the more demanding Configurations proved it was finally capable of tackling a ballet of this magnitude.

Schergen was the stager for both works. He first met Goh in 1976 at a post-show reception when Schergen was a principal at Pennsylvania Ballet (now known as Philadelphia Ballet). Schergen recalls being overwhelmed by his introductory viewing of Goh dances: “I thought he was a genius.” As Goh’s career started taking off, he convinced Schergen to be his ballet master at Washington Ballet, where Goh was resident choreographer until his untimely death in 1987 at the age of 39. Since his demise, Schergen has been the sole repetiteur for and the artistic director of the Choo-San Goh & H. Robert Magee Foundation, which owns the rights to Goh’s oeuvre and awards grants to support new choreography.

Configurations is famous for having been commissioned by Mikhail Baryshnikov for American Ballet Theatre soon after he took the reins there. Choreographed to American composer Samuel Barber’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Piano Concerto, it showcases 10 men and four women, inverting the usual male-female ratio in a ballet. Like the music, the piece has three movements; the wistful middle one features a couple in flux, originally danced by Baryshnikov and Marianna Tcherkassky.

ABT premiered Configurations in 1981 at Washington Ballet’s Golden Gala, with sets and costumes by Carol Vollet Kingston. American pianist John Browning, for whom Barber wrote the concerto, was so struck by Goh’s choreography that, according to Schergen, Browning asked to play for the ballet’s New York premiere. ABT’s complete rendition of it is found in the 1982 documentary Baryshnikov: The Dancer and the Dance.

Singapore Ballet’s revival of Configurations stemmed from the pandemic, during which Schergen began archiving the dozen Goh creations in the company’s repertoire. This included filming the steps in wide and close-up shots, and collating vital information such as the count structure, floor spacing, and lighting scheme. As the troupe had been presenting only the main duet from Configurations as a standalone excerpt, Schergen had not intended to document the full dance but felt compelled to do so for the archive.

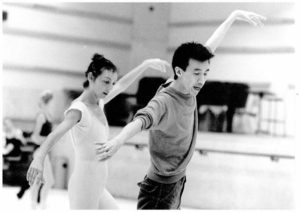

“Configurations is enormously complex,” Schergen says, explaining this is owing to its virtuosic Barber score and because the choreography is “built in a circle,” which poses challenges for the cast to keep time with one another. “I told the dancers, ‘This was not planned but I’ll work hard enough with you to get it right,’ and they responded perfectly.” Starring as the central pair, principals Satoru Agetsuma and Kwok Min Yi held their own in these mammoth roles.

Initially, soloist Timothy Ng thought Configurations was “formidable” when he watched snippets online. After learning the choreography as one of the ballet’s three lead men, the Singaporean realized it was “even more brilliant” than he first reckoned. “Dancing in Configurations is like being on a rollercoaster: you are pulled into an octane high before being plunged into a very soulful low, and then thrust up into another octane high. It is joyfully relentless.”

The ballet’s intricacy was noticed by British choreographer Tim Rushton when he was in town putting together a new piece for the troupe. This was the third offering to spring from the company’s quinquennial tradition of commissioning a work featuring all its dancers, starting with Taiwanese-American Edwaard Liang’s Opus 25 for its 25th birthday, and followed by Australian Tim Harbour’s Linea Adora for its 30th. Rushton’s Without You premiered as part of the 35th-anniversary mixed bill next to a restaging of Chant, which Val Caniparoli originally made for Singapore Dance Theatre in 2012.

To Rushton, part of what makes the troupe unique is its Goh repertoire, which “gives them a base that no other company has.” Yet Schergen wishes there was more widespread appreciation for Goh’s accomplishments. “There had never been an Asian choreographer in all of ballet history until Choo-San broke the race barrier,” Schergen asserts. “It was actually done by somebody from Singapore — I don’t think people are necessarily as aware or proud of that fact as they should be. Someone once said to me, ‘Does anyone even remember who Choo-San was anymore?’ If they don’t, I’ll remind them.”