Gerald Arpino: His time to be celebrated

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Gerald Arpino: His time to be celebrated

By Steve Sucato

The Joffrey Ballet, co-founded in 1956 by Robert Joffrey and Gerald Arpino, is proudly described on the company website as “America’s Company of Firsts.” It was the first dance company to appear on American television, the first to grace the cover of Time magazine, the first to perform at the White House, and the first classical dance company to use multimedia and a rock music score (Joffrey’s Astarte, to music by Crome Syrcus).

Over his 50 years with Joffrey Ballet, Arpino was key to shaping the company that he would eventually lead, in 1988, after Joffrey’s death. He continued as artistic director until 2007, a year before his own death in 2008.

Born in Staten Island, New York, in 1923, Arpino studied ballet with Mary Ann Wells in Seattle, Washington, and later modern dance with May O’Donnell, performing in her New York-based company in the 1950s. He was a leading dancer in the Joffrey Ballet until 1963, and, as resident choreographer, created nearly 50 ballets, more than a third of the company’s repertoire.

Facing mounting debt in excess of $1.6 million, in 1995 Arpino moved the company from New York to Chicago. Arpino said of the move: “My ties to Chicago are strong and deep. It was on the strength of the [Chicago critics’] glowing reviews that the fledgling troupe was able … to continue as a company.” Joffrey Ballet has been under the leadership of former company dancer Ashley Wheater since 2007.

The Gerald Arpino Foundation, founded to preserve and promote the choreography of both Joffrey and Arpino, initiated a multi-year (2022-2024) celebration to honour Arpino’s life and works, offering lectures, masterclasses, and setting Arpino ballets on several American dance companies and university dance program students, including at Brigham Young University Theatre Ballet and Chicago Academy for the Arts. The celebrations continue September 23-24 in Chicago with a mixed bill of Arpino’s ballets.

“A real individual” — that’s how Charthel Arthur Estner, a former Joffrey Ballet dancer (1965-1979) and current executive director of the Gerald Arpino Foundation, describes Arpino. Known to Joffrey Ballet dancers as “Jerry” or “Mr. A,” depending on the era, Estner says Arpino’s personality was very different from Joffrey’s. “Mr. Joffrey never yelled and was very appropriate in how he spoke and dressed. Jerry was the opposite; he would always come to rehearsal in sweatpants and sneakers, and was very physical and animated in the studio.”

In the 2003 Robert Altman film The Company, actor Malcolm McDowell played a character loosely based on Arpino. In the film, McDowell uses some of Arpino’s well-known mannerisms, such as referring to his dancers as “baby” or “babies,” and using the term “Zaahh” to inspire the energy and spark he wanted dancers to punctuate their movement with.

Valerie Robin, another former Joffrey Ballet dancer (2000-2013), says of Arpino: “He genuinely cared about the dancers, but you had to be a bit thick-skinned because of some of the comments he could make.” Arpino could also be funny at times, she says, recalling him using the building intercom to extol a proper diet: “Babies, remember fish, broccoli, and salad.”

As a choreographer, Arpino would often workshop material prior to its first rehearsal, says former Joffrey dancer Jodie Gates (1981-1995), now artistic director of Cincinnati Ballet. “He created directly on the people in front of him, calling on our technique to inspire him.” Unlike Joffrey, who came into the studio knowing exactly what he wanted in music and movement, “Jerry liked to present you with movement ideas, and he wanted you to make them your own,” says Estner. “It was very much a collaboration between him and the dancers.”

Arpino’s choreography reflected his outgoing and enthusiastic personality. “Jerry’s use of the torso, twerk of the body, and energy is the same throughout all his ballets,” says Estner. “Even in slow passages there is a certain dynamic that goes along with the music.”

Robin sees Arpino’s ballets as being neo-classical but in a style specific to him. “He shifted classical lines in his choreography, which was mostly exciting, sometimes showy, but always enticing,” she says. “It was just as great to dance his ballets as it was to watch them.”

Some of Arpino’s ballets had societal themes, such as 1968’s anti-war ballet Clowns and 1971’s battle-of-the-sexes Valentine; others were themed around his belief in angels, as in Arcs and Angels (1967) and Round of Angels (1983). Most of his well-known ballets, however, are non-narrative celebrations of movement and music. “He always said he wanted to entertain audiences with his works and wanted people to leave the theatre being glad they spent their money to see them,” says Estner.

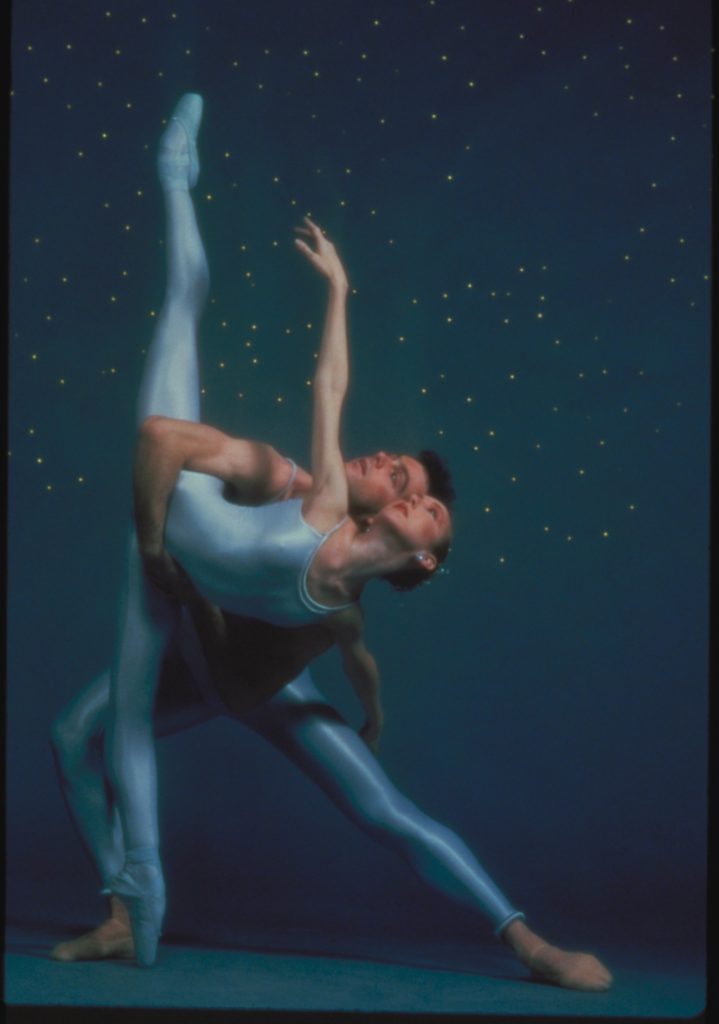

For the upcoming Centennial Celebration in Chicago, seven ballet companies from across the United States will perform nine of Arpino’s seminal works. Highlights of the line-up include Suite Saint-Saëns (1978), a ballet for 10 couples danced by Joffrey Ballet, which choreographer Agnes de Mille once described as “like standing in a flight of meteors.” Light Rain (1981), for seven couples, will be performed by Ballet West. Gates, who performed in it, says: “Arpino wanted us to dance from the pelvis but with elegance.”

1986’s Birthday Variations, danced by Oklahoma City Ballet, was described by former New York Times dance critic Anna Kisselgoff as a “sparkling showpiece of classical dancing.” 1971’s Reflections, to be danced by Eugene Ballet, features seven female and three male dancers. Set to Tchaikovsky, it is a perfect example of the Arpino style — high lifts, a flying pace, and classic beauty.

Kisselgoff once wrote: “I have often seen newcomers to the ballet seduced into loving the entire art form simply because Mr. Arpino’s accessibility seizes their imagination.”

Today several of his best-known ballets are still in demand, including Light Rain and Suite Saint-Saëns. Less known than his contemporaries in the United States — George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins in particular — Gerald Arpino nonetheless made a lasting impact, and his ballets have helped to define what American dance is.

Chicago’s Gerald Arpino Centennial Celebration takes place September 23-24, 2023.