Today’s Pacific Northwest Ballet: A graceful changing of the guard

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Today’s Pacific Northwest Ballet: A graceful changing of the guard

By Marcie Sillman

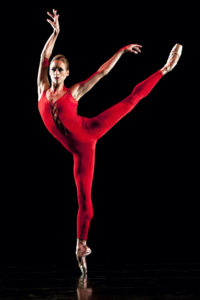

Pacific Northwest Ballet’s new season, opening later this month, will be the first in more than two decades without longtime principal Lesley Rausch. The ballerina was acclaimed for nuanced performances in everything from Swan Lake to Ulysses Dove’s very contemporary Red Angels.

She will be missed, but Rausch’s retirement is an inflection point for the Seattle-based company, a changing of the guard that’s helping to define the new face of American ballet. As it begins its 51st season, Pacific Northwest Ballet’s dancers are more ethnically diverse than at any point in company history. And they’re performing an ever-expanding repertoire of new works. The mandate for change comes from the top, but energetic young dancers are helping push those changes forward.

Rausch, who had been PNB’s most senior dancer, gave her final performance in mid-June. When the curtain came down, she was surprised by her colleagues’ emotional outpouring. “I told everyone, ‘I’m not dying!’” Rausch laughs. “You can call me when somebody’s having a bad day; put them on FaceTime and I’ll talk them off the ledge.”

For Rausch, it’s a continuation of a mentoring role she’s played for the past three years. Since the pandemic began, at least eight of her contemporaries have either retired or left for other opportunities. When the company returned to the studios in mid-2020, Rausch was one of only a handful of dancers over age 30, and an instant role model for her young colleagues.

“All of a sudden, everyone’s looking to you,” she says. Rausch may have missed the company members she’d danced with for so many years, but she grew to love being a mentor. “It’s something I’m going to miss almost as much as dancing.”

Dancers like 19-year-old Destiny Wimpye, who joins PNB’s corps de ballet this fall after an apprenticeship last season, will need to find new people to emulate. “Lesley helped me a lot with transitioning mentally,” Wimpye says. Going from the PNB School’s Professional Division to a job with a high-profile company was difficult. “It’s hard to come into a space feeling, like, am I supposed to be here?”

Wimpye’s boss, PNB artistic director Peter Boal, never doubted her abilities. “Destiny’s an engaging, intelligent, talented dancer,” he says She’s the kind of artist who catches his eye: musical, technically proficient, with a hunger to learn more.

Although Wimpye danced regularly with PNB during her final student year, she tried to temper expectations for her apprentice season. “I thought it would be a lot of standing around, not really dancing,” Wimpye explains. “I talked to different company members and they told me: ‘When you join the company, it will be culture shock.’”

Wimpye had no time to stand around. Her apprentice year included roles in Giselle and A Midsummer Night’s Dream as well as in Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s Khepri, and Crystal Pite’s The Seasons’ Canon, Wimpye’s particular favourite.

Ballet wasn’t her original passion. The Atlanta, Georgia native moved to Los Angeles to attend the Debbie Allen Dance Academy where she trained in a variety of styles. Wimpye also acted professionally, appearing in the acclaimed television drama This Is Us. Eventually she gravitated to ballet, attracted to both the technical and artistic challenges it presented. But, as a Black woman in an art form that has been dominated by white dancers, Wimpye knew she’d have to stand out to find a job with a major company.

Although PNB has had a number of BIPOC dancers over the years, few have identified as Black. Boal didn’t feel an urgency to push the status quo until after George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police in May 2020. “At that time we had one dancer that identified as Black in our company,” Boal says. “It was sort of whoa, are we asleep at the wheel?”

Wimpye is now one of 12 company dancers who are Black or of more than one race. That number includes PNB’s first Black principal Jonathan Batista as well its first Black female soloist, Amanda Morgan, both of whom Wimpye considers to be mentors.

This season more than 50 percent of PNB’s current roster of 45 dancers identify as Black, Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, or more than one race. But for Boal, diversifying PNB isn’t a numbers game. “I think the litmus test is not ‘how many people did I hire?’ It’s creating a culture of inclusion and acceptance.”

Wimpye believes PNB has definitely started to “walk the talk” when it comes to changing the status quo. “That’s one of the main reasons I wanted to join this company,” she says. “I felt welcome, not like a statistic. I think we [dancers of colour] are definitely pushing the company in a strong direction, and we’re pushing the dance world, too.”

Fellow dancer Kuu Sakuragi was initially drawn to PNB’s diverse repertoire, but he’s equally excited to be part of a company that is helping to reshape the art form. “In other big classical companies, everyone has the same kind of physique,” says Sakuragi. “It’s harder to stand out. Here, it’s okay to be yourself as long as you’re doing the work.”

Sakuragi speaks from personal experience. Standing just 5’ 6” tall, he’s not your typical ballet prince, but he’s one of PNB’s rising stars. The Seattle-area native began his ballet training through PNB’s DanceChance program, which offers scholarships to selected public school children. His teachers saw potential in the quiet boy, and pushed him to continue his training. Sakuragi rose through the company’s school, graduating from the Professional Division.

After that, Sakuragi danced at Alberta Ballet for three years, but his heart remained in Seattle. “I would see on social media what PNB was doing,” says Sakuragi. “I texted and asked if Peter [Boal] would let me take class with the company.”

He auditioned three times; in January 2020 Boal finally offered him a contract. Two months later, when the pandemic forced PNB to shut its doors, Sakuragi took company class over Zoom and tried to curb his impatience to dance with his dream company.

Once he was back onstage, Sakuragi quickly garnered attention for his stratospheric jumps and a dynamic stage presence that belies his offstage reticence. He’s performed an eclectic array of roles, from Puck in George Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream to featured solos in newer works by Pite, Alexei Ratmansky, and Alejandro Cerrudo.

Sakuragi and Wimpye exemplify the type of dancers Boal is seeking: hard-working team players who pivot easily between classical ballet and contemporary dance. That’s more important to him than crafting a uniform company “look.”

“If you’re looking for a paper cut-out, a replica of the dancer next to you, you won’t find that at PNB,” he explains. What inspires him is “an interesting mover, a musical dancer, a great stage presence.” The result is a company of dancers with the chops to perform an eclectic repertoire.

When PNB’s founding artistic directors Kent Stowell and Francia Russell hired Rausch in 2001, the company was closely associated with Balanchine’s ballets, which the choreographer provided at little or no cost to Stowell and Russell, who’d worked with Balanchine at New York City Ballet. After Boal took over in 2005, he began to acquire more contemporary work. Although that pushed some of the older dancers like Rausch outside their comfort zone, it wasn’t necessarily bad for their careers.

“When Peter came, he gave me a lot of opportunities to do featured roles,” says Rausch. “It helped me to develop confidence that I was able to do more than I thought I could.” In her penultimate season, Rausch danced in what she calls her first sock ballet, a work by Alonzo King, and as Odette/Odile in Swan Lake.

Wimpye loves the contemporary work she performed last season, but she’s eager to learn the classical roles Rausch excelled in. “I just want to do everything,” Wimpye says. “My mature vision of myself is dancing something like Romeo and Juliet.” PNB performs a 1996 version of this Shakespearean classic, choreographed by Ballet de Monte Carlo’s Jean-Christophe Maillot. It’s one of the company’s most popular ballets, and Wimpye is itching to dance Juliet. “I really connect with super-emotional roles, where you get to be vulnerable onstage,” she says.

Wimpye won’t get to fulfill her dream this season, but PNB will offer the opportunity to stretch her dramatic chops in the classics Coppélia and Swan Lake. Newer ballets by Twyla Tharp, Jessica Lang, Jirí Kylián, Pite, and Cerrudo are also on the schedule.

PNB’s audiences have grown accustomed to the company’s new repertoire, danced by one of the most diverse major ballet companies in the United States.

Boal believes ballet, inevitably, must change to reflect the times. “It’s a new world,” he says. “I used to think about running a ballet company, but now I think about running a microcosm of that new world. I think at PNB we really value the people around us and the community we live in. That sense of belonging and inclusion has never felt more right.”

Pacific Northwest Ballet opens its 51st season September 22 at McCaw Hall with the program Petite Mort, featuring two works by Kylián and Alexander Ekman’s Cacti.