A Ballet, a Book: Fascinating Oskar Schlemmer

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- A Ballet, a Book: Fascinating Oskar Schlemmer

By Jeannette Andersen

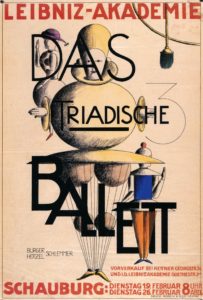

Today Oskar Schlemmer’s The Triadic Ballet (Das Triadische Ballett) is considered an avant-garde masterpiece and a milestone in the dance and art world from the beginning of the 20th century. To celebrate the work’s 100th birthday, the Bayerisches Junior Ballett München concluded their 2022-2023 season with sold-out performances of the ballet, and in June, a book by Frank-Manuel Peter, Oskar Schlemmer und der Tanz (Oskar Schlemmer and the Dance) came out (published by Wienand in German only).

Peter is director of Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln (German Dance Archive Cologne) and his 640-page book is based to a large extent on never-before-published material from this archive: letters, photos, drawings, excerpts from memoirs, and reviews almost all pertaining to The Triadic Ballet and its arduous journey from idea, to stage, to fame.

Peter is director of Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln (German Dance Archive Cologne) and his 640-page book is based to a large extent on never-before-published material from this archive: letters, photos, drawings, excerpts from memoirs, and reviews almost all pertaining to The Triadic Ballet and its arduous journey from idea, to stage, to fame.

Oskar Schlemmer (1888-1943) was a painter, sculptor, and stage designer. From 1920-1932 he taught at the famous Bauhaus school and was instrumental in implementing new ways of defining art. The idea behind Bauhaus was not only to eliminate the boundaries between arts and crafts, but also to combine the arts to create a new, total work of art, or Gesamtkunstwerk. Schlemmer was preoccupied with der Mensch (the human being), not in the emotional sense, but as pure form, which would represent the ideal human being. At Bauhaus he even taught a class called Der Mensch. In his more radical paintings, humans are reduced to faceless figures made out of triangles, cylinders, and circles. His most famous painting, Bauhaustreppe (Bauhaus Stairway) from 1932, hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

To express his ideas artistically, Schlemmer thought painting too static a form and found dance more suited. Having no formal dance training, he started to collaborate with the ballet dancers Elsa Hötzel and Albert Burger in 1912. Together they developed the concept for The Triadic Ballet. Interrupted by World War One, the ballet didn’t have its premiere until 1922. By 1923, the two dancers and Schlemmer had fallen out about the rights to the choreography and costumes, and, since then, the ballet has been attributed solely to Schlemmer. Over the years, including in Schlemmer’s time, it has been danced to different music, from Mozart to Hindemith.

To express his ideas artistically, Schlemmer thought painting too static a form and found dance more suited. Having no formal dance training, he started to collaborate with the ballet dancers Elsa Hötzel and Albert Burger in 1912. Together they developed the concept for The Triadic Ballet. Interrupted by World War One, the ballet didn’t have its premiere until 1922. By 1923, the two dancers and Schlemmer had fallen out about the rights to the choreography and costumes, and, since then, the ballet has been attributed solely to Schlemmer. Over the years, including in Schlemmer’s time, it has been danced to different music, from Mozart to Hindemith.

In the original version, three dancers performed 12 dances in 18 different costumes against three different backdrops, yellow, pink and black, with each colour representing a mood (respectively cheerful, festive, mythic). The dancers were depersonalized, wearing masks and colourful costumes made out of wood, wire, synthetic materials, felt, and velvet. The costumes were heavy, each one restricting the dancer’s movements in a specific way, their roles named after the material or the primary mode of movement: Spiral, Goldball, Wirefigure, Diver, The Abstract, Diskdancer, to mention a few. The choreography included solos, duos, and trios, with movements from ballet and folk and court dance, as well as abstract geometric form.

During Schlemmer’s time, most critics saw the ballet as a failed attempt to develop something new. This was the period when Mary Wigman, Rudolf von Laban, and Émile-Jaques Dalcroze were experimenting with freeing dance from all formal restraints, while Schlemmer defined dance as a stylized body, a form moving in space. The ballet was not performed often, mostly due to Schlemmer’s lack of managerial skills and finances.

While teaching at Bauhaus, Schlemmer also created his now famous Bauhaustänze (Bauhaus Dances, made between 1926-1929) based on the same principle, a human being seen as a form moving in a geometrical space. The titles of the scenes included Roomdance, Formdance, Poledance, and Hoopdance. In 1967, former Wigman student Margarete Hasting (1909-1972) reconstructed these and The Triadic Ballet. She received so much attention in Germany that dancer Gerhard Bohner (1936-1992) did a new reconstruction of The Triadic Ballet in 1977, which toured the world for the next 12 years.

There are many photos and drawings of the ballet, and some of the original costumes have been preserved, but there is almost no information about the choreography. Bohner admitted that he could not reconstruct the actual movements, only the process Schlemmer must have gone through from costumes to movements.

In 2014, 70 years after Schlemmer’s death and with the expiration of the copyright, Ivan Liška and Colleen Scott restaged Bohner’s version for the Bayerische Junior Ballett. Between 1977-1989 they had toured with Bohner’s group, performing the ballet more than 85 times. In their version, 18 dancers perform the 12 sections, and some of the dancers need two wardrobe attendants to get in and out of the heavy costumes.

Schlemmer wanted to create the ideal human being through stylizing his figures by turning them into faceless abstractions. But because of the individuality the costumes create, each figure appears to have its own personality and to be telling its own story. They become like every human being trapped in their own mental and physical reality, which makes them easy to identify with. Perhaps that partly explains the popularity of the ballet today.

Much has been written about Schlemmer and his dances but, for the first time, in Oskar Schlemmer und der Tanz, Peter brings together 32 pieces on dance and theatre written by the artist himself. Along with the many until now unpublished letters from and to Schlemmer, the book presents a portrait of a man obsessed with dematerializing the body in order to find a form through which the new German ballet could develop.