London: Pite’s Light, Ek’s Rite and Peaky Blinders, the ballet

- Home

- City Reports 2020 - 2023

- London: Pite’s Light, Ek’s Rite and Peaky Blinders, the ballet

By Sanjoy Roy

The Royal Ballet has followed through on the success of Crystal Pite’s one-act Flight Pattern (2017) by expanding it into a full-evening triptych called Light of Passage. All three acts are cast in shadows set against suspended auroras of light, accompanied by the ebb and flow of Henryk Górecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, and each is an angle on the theme of “passage”: refugees in the first act, which ends with the image of an absent baby; youth and age (movement into and departure from the world) in the subsequent ones. The focus in each act is on large groups, which serve as the bigger choreographic body from which more intimate solos, duets, and smaller groups sometimes emerge to spotlight individual stories and sentiments.

In Flight Pattern, the story is of a mother, her partner, and their lost child, represented by the forlorn folds of the coat she cradles. In Covenant, six real children are the bright white beings whom the group helps to guide and carry. In the final act, Passage, two older performers from the Company of Elders enact a mortal separation, as one of them, despite all efforts and wishes, leaves the stage. If the stories hold a narrative line, the choreographic interest lies in Pite’s highly dynamic ensembles, skilfully composed yet always in flux and never regimented: although these groups are large, there’s a humanizing awareness of the individuals within them.

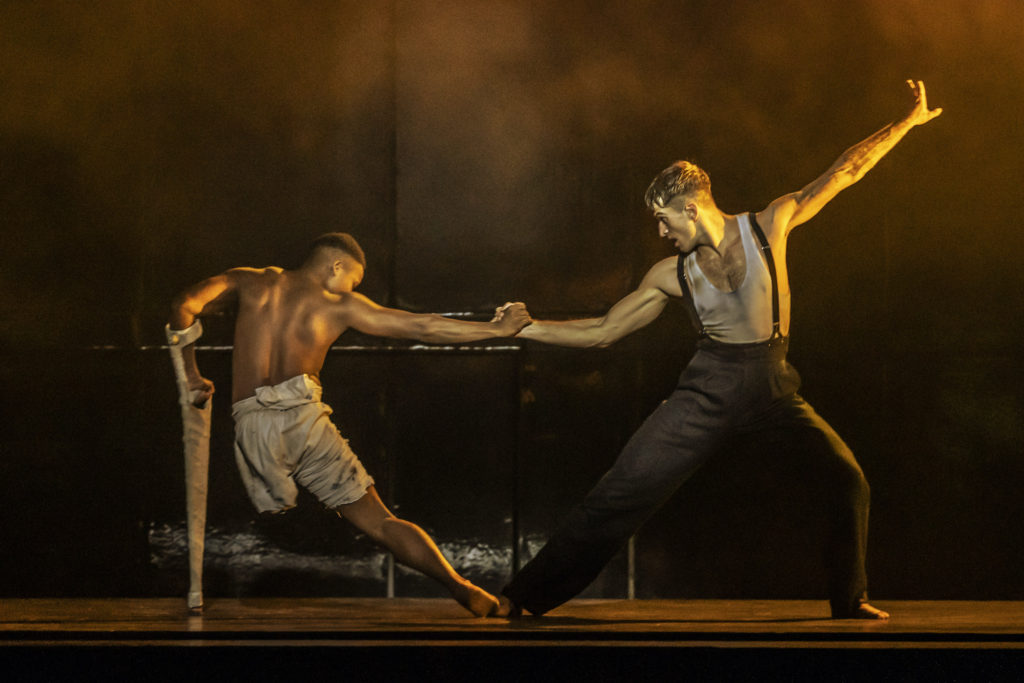

Perhaps Light of Passage is a little too tasteful: lots of poetic beauty, not a trace of blood and guts. None could level that criticism against Rambert’s Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, inspired by the cult TV series, its creator Steve Knight working here as writer. Choreographed by Rambert director Benoit Swan Pouffer, this darkly thrilling dancework has all the hallmarks of the TV series: growling indie-goth music (played live), a heavy Birmingham accent for the narration, grimy mid-century costumes of flat caps and trench coats, scenes of betrayal, hedonism, scheming — above all, lots of violence, in gang fights, in bar brawls, in brutal and bloody murders that just keep on coming. While the opium-den scene strikes a rare wrong note for its Orientalist clichés, the overall production is slickly choreographed, sleekly danced (the Rambert dancers, as ever, on excellent form), and very stylish indeed.

It’s also a bold step for Rambert outside their familiar territory. In London, Peaky Blinders settled into an extended season at the Troubadour Theatre, out in the suburbs of Wembley, not at all your usual dance venue. Nor were the audience dance insiders; rather, they were a wide range of people looking for a great evening out, which — with the bar and foyer decked out to match the series style, fans sporting the trademark haircuts, caps, and coats — they certainly got. Who knows whether these audiences might cross over for Rambert’s other repertoire, but on its own terms, this is a hit.

Many choreographers have been drawn to the flame of Stravinsky’s mighty Rite of Spring, but few have withstood its force. And still, they keep coming. More versions are scheduled to arrive in London next year, following two starkly austere treatments that landed at Sadler’s Wells late this autumn. First was Mats Ek’s Rite of Spring, a world premiere for English National Ballet, with its strangely defamiliarizing costumes: stiff, somewhat awkward pink kimonos, designed (by Marie-Louise Ekman) as if to impede movement more than enable it. That’s in keeping with the scenario: a woman’s marriage to an unknown man, arranged by her mother and father. Freedom of choice, as with freedom of movement, is constrained.

The dance style is full of frustrations, flat-armed reaches and lunges curtailed by counter-pulls. Only in one scene — where the betrothed couple (Emily Suzuki and Fernando Carratalá Coloma) discover each other alone, outside of society’s surveillance — does the movement release into a more personal if still testy encounter. For the rest, the characters are duty-bound, parents (Erina Takahashi and James Streeter) backed by separate corps, as if their roles as mother and father were freighted with expectation.

All this reminds me less of the Stravinsky/Nijinsky Rite of Spring than of Stravinsky/Nijinska’s Les Noces, another story of an arranged marriage; perhaps that’s indicative of why music and dance didn’t seem to align here. Yet another austere take on the Rite certainly did, partly because its approach was not through character and narrative, but through rhythm and iconography. In La Consagración de la Primavera, flamenco maverick Israel Galván scatters the stage with bare boards, miked for sound, while onstage pianists Daria van den Bercken and Gerard Bouwhuis render the score in its stark, two-piano transcription.

In direct homage to Nijinsky, Galván enters with flat, frieze-like steps, to an improvised piano prelude of impressionist sonorities that precedes the arrival of Stravinsky’s music. You can see the flamenco lineage in the sharp direction of arms and head, the downward drive of the feet, the finger snaps and body slaps, whipped spins and held stillness. But all phrasing, all flow and finish, has been expunged: these are fragments of a style, exposed as the moving parts of its mechanism and set in motion by the gears, cogs, and hinges of the human body — just like the music being hammered through the wood and wires of the pianos, never settling into a form or rhythm.

Soon, underscoring everything, comes the unnerving rattle and thunder of Galván’s loose-cannon footwork. The stage becomes both mechanical soundbox and cultural echo chamber, in which you recognize everything but count on nothing. Instead of surrendering to Stravinsky’s mighty score, Galván has managed to join forces with it.

Finally, with Christmas just past, it’s worth mentioning Ben Duke’s Ruination at the Royal Opera House’s downstairs Linbury Theatre, a morbidly entertaining alternative to The Nutcracker playing simultaneously on the main stage upstairs. (The locations are apt: Duke’s piece is set in the underworld.) Ruination continues his run of works marrying archetypal stories (here, of Medea and Jason) with the flawed, humdrum lives of ordinary people (they squabble, they’re bored, they tell fibs). As well, Duke builds on Cerberus, his previous work for Rambert, in treating the stage as a kind of life, with an exit, stage left, as a passage into death. Unlike the streamlined poetics of Pite’s Light of Passage, this is a total ragbag. Funny, tragic, ironic, sincere, vengeful, forgiving, archetypal, individual — it’s all these things and more, just like us.