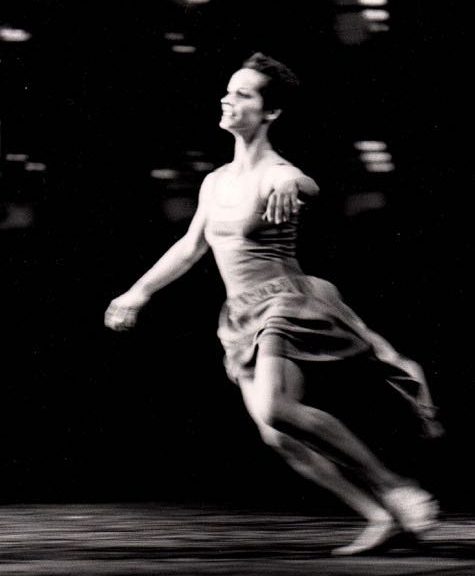

Taking Care of the Dance: Ginelle Chagnon, rehearsal director

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Taking Care of the Dance: Ginelle Chagnon, rehearsal director

By Philip Szporer

The rapturous crowd at this past year’s Prix de la danse de Montréal listened when Ginelle Chagnon launched into her acceptance speech. The beloved figure had just received the Ethel Bruneau Prize, an award created expressly to put the spotlight on members of the dance community who work in the shadows. “Having been in the business for 40 years,” she said, “I have had as many titles as the artistic projects I’ve participated in: rehearsal director, assistant to the choreographer, creation assistant, dramaturge, second eye, third eye, outside eye, eagle eye, artistic advisor, co-choreographer, coach, accompanist, movement specialist, artistic direction, mentor, muse, archivist, reviewer… and I’m running out of time.”

Recalling the event a few months later, her hearty laugh breaks through the airless Zoom connection as we chat online from our Montreal homes. “So many allusions to the eyes,” she says, smiling. “My eyes are always wide open!”

The award was well deserved. Chagnon has critically altered the face of Quebec dance, having contributed in the development of major choreographic creations with numerous companies such as Danse Partout, Montréal Danse, the Fondation Jean-Pierre Perreault, and Fortier Danse-Création, and as a mentor to generations of artists.

“When I accepted my prize, and I don’t like prizes, it was to publicly acknowledge those very people [in the shadows],” says Chagnon. Their work is intricate and complex, and about so much more than teaching steps or showing how to do them. “I now call myself a dance artist, because it covers so many bases. Just saying rehearsal coach looks onto one window only.”

Chagnon zeroes in on a fundamental truth: the titles may be porous, but the intention is always to support the work. “It’s not about whether [dancers are] doing it right or wrong, but is the experience we wish for happening? Whether it’s in a classroom, onstage, or in rehearsal, it’s about making sure the dance is taken care of,” she says. “We’re caretakers.”

Dance seems to have accompanied Chagnon all the days of her life. Early memories in Quebec’s Laurentian Mountains, in Ste-Marguerite-Station, a countryside hamlet named for its train station, resonate. Her father worked as the station attendant, and the family lived in the station. “In the middle of nowhere, at the top of a hill,” says Chagnon. The youngest of four children, she explored the wild outdoors and walked the rails. “It was the best childhood ever.”

It was there that she was exposed to ballet. One summer, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens founder Ludmilla Chiriaeff decided to scout new talent in the area. She introduced free ballet classes at a community centre in Ste-Adèle. Chagnon’s two older sisters signed up, and she tagged along. She recalls hanging around the ballet barres. “I was standing imitating everybody. That’s how it started,” she recalls. “Dance chose me. I can remember the feeling of hanging on the barres as a young child.”

Chiriaeff was key to Chagnon’s growth as an artist. “She was the first person to show me that passion can exist. She was totally living for the dance. And to nurture Quebec dance.” Soon she was taking the train to Montreal for Saturday morning ballet classes at Les Grands’ downtown studios on Stanley Street, sandwiched between a billiards club and a judo studio, and next door to the Chez Parée strip club. “That’s where [Fernand Nault’s] The Nutcracker was born,” says Chagnon. “They were glorious years.” She was in his first Nutcracker, in 1963, as a child, with Nault choreographing on the children.

She rose among the company ranks between 1971-1974, first an apprentice, then a full company member. “All these Americans, with really strong technique, were arriving. We didn’t feel we were up to par. But there’s something else in dance. It’s not just technique.” Beyond steps, styles, and ballets, the stories and metaphors stemming from encounters with artists the calibre of Nault and Chiriaeff gave the local dancers something else, an expressivity and distinct stage presence.

Her role in dance, she knew, could be something other than as a performer. “I was always watching the process. I knew everyone’s role,” she recalls. She became the go-to replacement. “I was interested in what was going on, not just being in it.” Observation was transformative, then and now, and informs her interactions with artists.

Chagnon recognized that she belonged. “I mean, why would you want to step away from that?” But step away she did. She was pregnant, had moved with her then-husband to a farm in Harrow, Ontario, raised two kids, and worked on neighbourhood farms until 1983. When the marriage dissolved, she moved back to Montreal, took teacher training classes, and began to “get my body back in shape.”

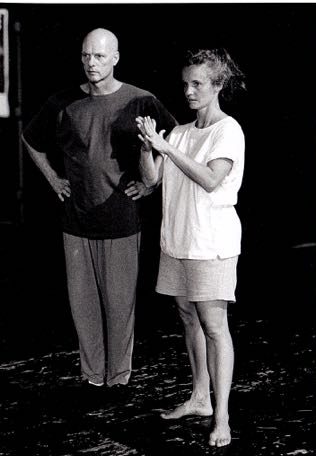

Eventually she gravitated to Danse Partout in Quebec City. There she met Jean-Pierre Perreault, who had come to the contemporary dance company to remount Calliope (1982). She was learning one of the duets. “He pulled me aside and said, ‘I want you to be the rehearsal director.’” Perreault had been watching her process the execution of the movements, and thought she grasped what he was looking for. “That was the first time a choreographer actually called me in to do this work.”

Gigs with other dance companies followed, and she finished her master’s degree in teaching, but Perreault remained an anchor. “He created not only a world with his work, but very particular groupings and an atmosphere that was very nourishing. Perreault’s work became a family ground of sorts,” she says. A similar feeling of belonging surfaced with Paul-André Fortier, another iconic experimentalist in Quebec dance.

“Strong individuals and strong stuff was happening,” she says. It’s no exaggeration to say that Chagnon had a role to play in shaping the work and its vocabulary. “When people trust you, you want to live up to the responsibility.” She is still remounting Perreault’s work, with Nuit presented by Laurence Lemieux’s Citadel + Compagnie June 8-10 in Toronto.

As Chagnon recalled in Jeu magazine, in a profile dating from 2000, “I focus on what can touch the sensibility of a viewer. I also look for what is particular to the work I see.”

The watching, from her vantage point, is “always about better serving the work.” She’s there to expertly guide the performers in understanding how their own body instrument works, and to get the physicality to a place that’s expressing something. Chagnon is alert to achieving integrity in the creative context the choreographer intended, and, at the end of the day, to have the unquantifiable come to life.