Lynn Seymour: A great dramatic ballerina for the modern stage remembered

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Lynn Seymour: A great dramatic ballerina for the modern stage remembered

By Michael Crabb

Lynn Seymour, in one of many artistic excursions beyond the world of classical ballet, made her debut with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 1971 channeling Janis Joplin in Ailey’s Flowers. Seymour arrived onstage smoking an oversized joint — allegedly fake. Not many months later she was back at the Royal Ballet in London to make her entrance in the first act of Kenneth MacMillan’s expanded version of Anastasia, tomboyishly cruising in on roller skates.

Lynn Seymour, who died on March 7 on the eve of what was to have been a celebratory 84th birthday lunch, could always be relied upon to disrupt expectations.

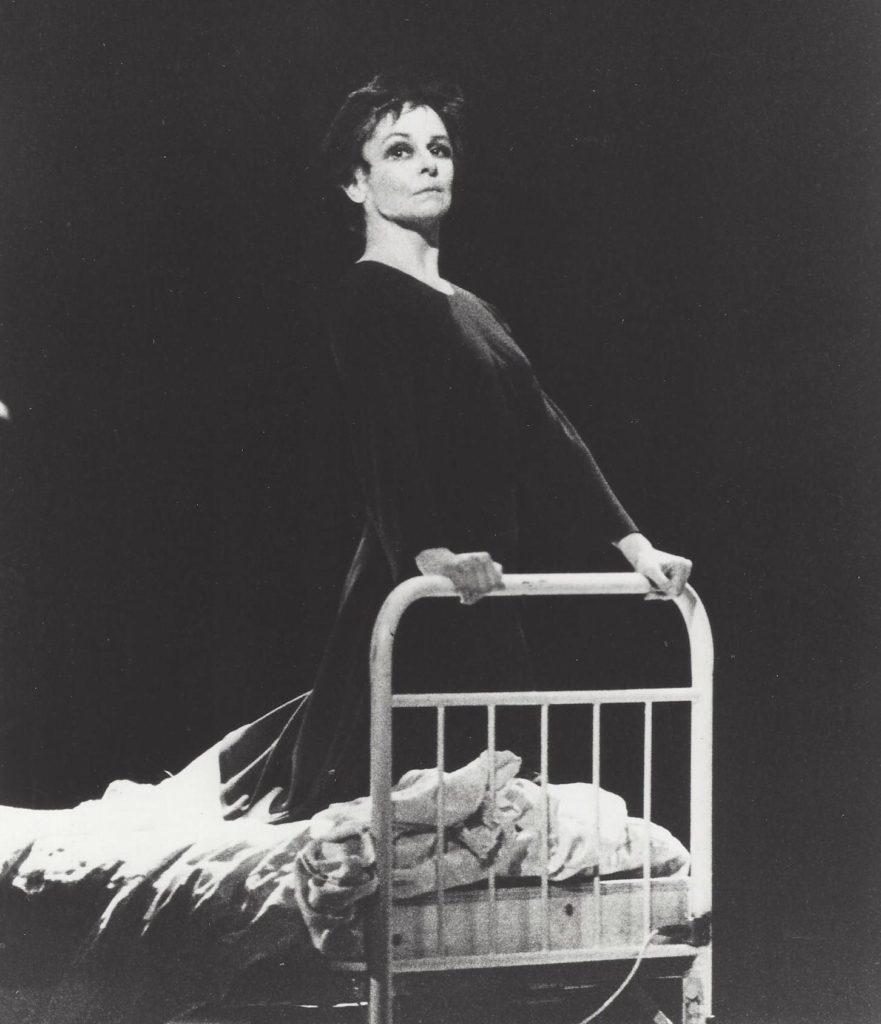

Seymour redefined what it is to be a ballerina in the modern age, injecting the many dramatic roles created for her with thrilling, at times unsettling emotional intensity. Whether as a girl dangerously misconstruing an older man’s predatory attentions in MacMillan’s The Invitation (1960), or portraying the anguish of a mature woman’s conflicted attraction to her son’s young tutor in Frederick Ashton’s A Month in the Country (1976), Seymour was a dance-actor beyond compare. And then, of course, there was Juliet.

By the early 1960s, Seymour and her onstage partner Christopher Gable had become part of MacMillan’s favoured inner circle, inspired by a new wave of realism in British theatre. When the Royal Ballet asked MacMillan to choreograph Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet, he chose to create the title roles on his young favourites. Seymour was so committed to the project that she aborted a pregnancy rather than sacrifice the role. (She and the first of her three husbands split not long after.)

Everything seemed headed toward a successful opening night when MacMillan had to explain to a devastated Seymour and Gable that Royal Opera House management was insisting Fonteyn and Nureyev must dance the February 1965 world premiere. When Seymour did get to dance the role, she injected her Juliet with a determination and visceral passion that caused a sensation.

Nevertheless, the bitter experience prompted both MacMillan and Seymour to decamp for Berlin Opera Ballet until the choreographer was summoned back to head the Royal Ballet on Ashton’s retirement in 1970. Seymour, now the mother of twin boys with Polish dancer Eike Walcz (not one of the husbands), returned as a guest artist, although a cycle of ill-health and injuries blighted these later years.

Berta Lynn Springbett was born in Wainwright, Alberta, on March 8, 1939, the only daughter of Ed Springbett, a dentist, and his wife Marjorie. Lynn’s older brother, Bruce, was a champion sprinter. When she was three, her father moved the family to Vancouver where she began ballet classes with Nicolai Svetlanoff. The childhood inspirations of the 1948 movie The Red Shoes and seeing Alexandra Danilova dance Coppélia ignited Seymour’s ambition to pursue ballet as a career.

When the Sadler’s Wells Ballet toured to Vancouver in 1953, Seymour presented herself for audition and at age 14 moved to London on scholarship to enter the company school. Years later, one of Dr. Springbett’s young patients was a Vancouver ballet student named Kaija Pepper, the future editor of Dance International. Pepper recalls the pleasure of viewing the photos of her dentist’s by now famous ballerina daughter that adorned the waiting-room walls.

Seymour graduated into what had just been renamed the Royal Ballet in 1956, first as a member of the opera ballet, then of the touring company, and by 1958 the main Covent Garden troupe where Fonteyn, now in a rejuvenating partnership with Soviet defector Rudolf Nureyev, still cast a long shadow over a younger generation of gifted ballerinas. Even so, Seymour’s star shone bright and at age 20 she became a principal dancer, dutifully taking on the canonical classical roles while constantly yearning to create new, dramatically complex characters.

Both Ashton and MacMillan admired Seymour’s distinctive talent, the fluidity and musicality of her movement, her expressive pointe work, dramatic naturalism, and spontaneity. Ashton brought Seymour and Gable together as partners for the first time in 1961 as the title leads in The Two Pigeons. It was more than a decade before she worked with the celebrated choreographer again. That was in A Month in the Country and, also in 1976, Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan. It was toward MacMillan and his fascination with troubled misfits and vulnerable souls that Seymour more naturally inclined.

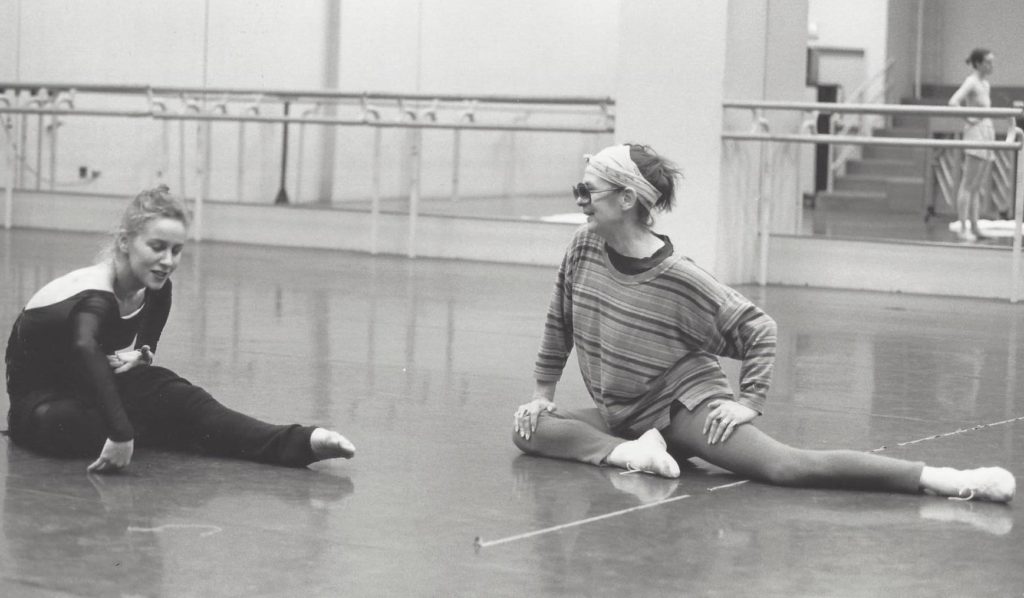

In great demand internationally as a guest artist, Seymour heeded the call of the National Ballet of Canada on several occasions in the period 1964 to 1970. She returned to Toronto in 2008 to coach principal dancer Jennifer Fournier in Five Brahms Waltzes for her farewell performance.

Seymour briefly held artistic directorships in Munich and Athens. She also choreographed a number of works in the 1970s. In 1983, she acted in a Canadian-German co-produced television series of The Little Vampire. On film, she was featured in Herbert Ross’ 1987 Dancers and portrayed ballerina Lydia Lopokova in Derek Jarman’s experimental 1993 biopic, Wittgenstein.

Her natural territory nevertheless remained the live stage. Emerging from official retirement in 1987, she reunited with Gable to portray the mother of British artist L.S. Lowry in Gillian Lynne’s A Simple Man at Northern Ballet. The following year, with English National Ballet, she made her debut as Tatiana in John Cranko’s Onegin and in 1989 reprised her role as Anastasia when the company toured to New York’s Metropolitan Opera House. Seymour thrilled London audiences when she appeared in the mid-1990s with Matthew Bourne’s Adventures in Motion Pictures in his radical re-imaginings of Swan Lake and Cinderella.

Each fall since 2000, second year students of Britain’s Royal Ballet School are invited to perform solos of their own choosing, prepared without assistance. These are judged not so much for technical accomplishment as for the candidate’s ability to embody character and convey drama. There is of course an incentive, appropriately named the Lynn Seymour Award for Expressive Dance. This year’s competition will inevitably be tinged with sadness but also, one hopes, with a spirit of celebration and with a strong commitment to Seymour’s example, always to put artistry before athletic spectacle.