Boston Ballet: Jorma Elo / Fifth Symphony of Jean Sibelius , Wayne McGregor / Obsidian Tear

- Home

- Reviews 2014 - 2019

- Boston Ballet: Jorma Elo / Fifth Symphony of Jean Sibelius , Wayne McGregor / Obsidian Tear

For its fall production, Boston Ballet presented a double bill at the Boston Opera House featuring Wayne McGregor’s Obsidian Tear and the premiere of Jorma Elo’s Fifth Symphony of Jean Sibelius. Both works were accompanied live by the Boston Ballet Orchestra, which began the evening by playing Sibelius’ Finlandia, a “symphonic poem” that is at times resonant and smooth, and at others rousing and triumphant.

Composed in 1899, Finlandia remains a symbol of Finnish patriotism during the region’s struggle for emancipation from the Russian Republic. The Finnish-themed evening — Elo is from Finland and Obsidian Tear is set to orchestral works by Finnish composer Esa-Pekka Salonen — celebrated the centennial of Finland’s 1917 declaration of independence, an event Boston Ballet’s Finnish-born artistic director, Mikko Nissinen, was clearly proud to present.

Fifth Symphony of Jean Sibelius by Elo, Boston Ballet’s resident choreographer, proved most notable. It begins with a dimly lit stage of neutral tones, with 20 dancers gazing stoically, seemingly past the confines of the theatre walls. Above them floats an ominous black ring, which the dancers begin to partner, in unison, beneath.

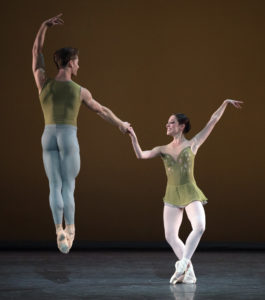

The scene is quickly disrupted by the emergence of a soloist in pale blue (Ashley Ellis). Ellis introduces a barrage of new pairs who swiftly dart across the space dressed in mauve and olive against an ever-changing backdrop, from lavender to amber. Brimming with the muted hues of nature, the work begins to evoke the four seasons, swirling throughout the space and echoing the ring above and the cyclical pattern of time itself.

In Fifth Symphony, Elo plays off Sibelius’ lighter musical moments with quick-changing, folksy footwork. Throughout, attention to detail is given to each step’s completion. Never is the dancer left stagnant, as every pirouette transitions seamlessly into a triumphant forced arch precisely timed with a partner’s, or glides into a surprising développé in the opposite direction before ever touching the ground. These details give the traditional ballet vocabulary a modern edge by omitting dramatized landings and unnecessary flair. Instead, the dancers speed past one another with fluid strength, like leaves caught in the wind.

A series of duets follow, interrupted at times by Ellis, who inserts mischievous levity into an otherwise elegant atmosphere. Where the first duet floats with weightless lifts and leans, the second is punctuated by each precise note from the orchestra. A joyous couple in green is swiftly followed by a bittersweet duet of longing and weighted solemnity. As the work builds to its climax, Ellis returns once more, sprawling herself playfully across the front of the stage as the full cast of 34 behind her appears almost as a breathing landscape.

Elo’s Fifth Symphony is masterfully choreographed, though its set design, also by Elo, feels out of place. Aside from the brief moments when the dancers circling below mimic the suspended circle above, this large black ring tends to distract rather than enhance, taking focus off the stage and into the space above.

In direct contrast to Fifth Symphony was McGregor’s Obsidian Tear, a co-production between the Royal Ballet (where McGregor is resident choreographer) and Boston Ballet, which premiered in London last year and made its American debut here. McGregor, who is known for his unexpected reconfigurations of classical ballet language, is regularly commissioned worldwide to choreograph for dance, theatre, opera, film and fashion shows.

The bones of the work are solid. The program notes explain that the title refers to a specific type of quickly cooled volcanic rock and that the action delves into the double meaning of the word “tear.” This imagery, coupled with composer Salonen’s symphonic poem Nyx (which is inspired by the powerful and alluring goddess of the same name), is richly developed onstage through the use of brilliant red lighting, a foreboding set and sinewy choreographic phrases. The tumultuous nature of the piece feels deeply rooted in this volcanic rupturing, with its nine dancers struggling against one another while balancing violence with grace.

Where the work disappoints is at times in the movement itself, and at others in the dancers’ interpretations. McGregor combines traditional ballet technique with unconventional expressive phrase work to create a hybrid that covers the gamut of both, and this frequently lacks cohesion.

An overly traditional preparation before a turn feels disconnected from an otherwise organic phrase. Likewise, the emphatic flicking of the wrists and flailing of limbs appear too loose for this otherwise precise technique. As well, the dancers’ interpretations varied dramatically, creating an unpolished appearance for a company of this calibre. Other moments appeared over–rehearsed. McGregor’s choreography proffers several strong and emotionally charged scenes of discord, yet the weight of these moments was often lost as Boston Ballet’s dancers overly anticipated each push, lift and thrust to the point of seeming disingenuous.

The evening’s two choreographic works could not be more dissimilar, yet both made an important contribution to honouring Finland’s historic centennial, beautifully integrating art and artists from the country’s past and present.

— MERLI V. GUERRA

DI SPRING 2018

Photo: Rosalie O’Connor, courtesy of Boston Ballet