Malpaso: Barton, Delgado, Tayeh, Naharin /Mixed Bill

- Home

- Reviews 2014 - 2019

- Malpaso: Barton, Delgado, Tayeh, Naharin /Mixed Bill

The Havana-based Malpaso Dance Company gave an evocative performance of four distinct pieces at the National Arts Centre on January 19. This spectacular Ottawa debut of Cuba’s first independent dance company, established in 2012, stood out in its equal showcasing of male and female choreographers.

The first piece, Indomitable Waltz (2016) by Alberta-born Aszure Barton, was set in motion when a male dancer rotated his shoulder with force and beauty. Body isolations punctuated Malpaso’s signature vernacular, which fuses Afro-Cuban rhythms, Cuban ballet culture and vibrant modern dance.

As eight dancers sculpted trios, duets and solos, their intricacy conveyed Barton’s vision, which she has described as being about the complexity of the soul. Her sumptuous waltzes explore this idea through multi-faceted choreographic moments that jumble up the company’s dance vocabulary. This meshing of styles is Barton’s choreographic trademark. Dunia Acosta performed a rond de jambe en l’air with a bent knee and a flexed foot; the angular joints of the Afro-Cuban repertoire were swiftly reshaped back into ballet with an arabesque. Solo dancers were lifted by pairs in a dual set of triads in a whirl of contemporary dance and ballet. Esteban Aguilar, apart from the others, stepped rhythmically in place to call forth salsa and its roots in the 19-century mix of Cuban music and dance known as son.

The jaggedness of the choreography is accentuated by six disconnected scores, from the crispness of Balanescu Quartet’s Waltz to the frenzy of a string quartet by Michael Nyman. Musical and choreographic disharmonies, both pitfalls of the piece, were smoothed over by the dancers’ fluidity and athletic splendour. Their masterful transitions between assorted musical themes and dance traditions pieced this scattered work into a luscious blend.

In Ocaso (2013) by Osnel Delgado, who co-founded Malpaso, Delgado and Beatriz García performed a provocative and touching duet that conveys the ebb and flow of intimacy in relationships through an amalgam of modern dance and ballet.

The give-and-take in romantic partnering is captured through the use of space. Each dancer alternated between rolls and moves on the floor, standing figures and leaps. Multiple architectural levels combined with the pair’s artistry to turn shifting emotions into palpable sensations.

Delgado’s outstanding deep and controlled pliés in second position and his grand jetés, executed with strength and lightness, embodied this personal interchange. García excelled in her interplay of expressive roles. As if a marionette controlled by her male partner, she broke free, took the lead by grabbing and supporting him, and captured the limelight in solo jetés and spins.

The thunderous timbre of Autechre’s Parallel Suns, the urgency of Kronos Quartet’s White Man Sleeps and the haunting serenity of Max Richter’s Sunlight accompanied their fluctuating relations. Ocaso’s brilliance lies in the clarity of the correspondence between movement and message even though its drive to enact a singular theme is too repetitious.

New York City choreographer Sonya Tayeh describes her work, which bridges the worlds of television, music, theatre and concert dance, as combat jazz. Face the Torrent (2017) vibrates with street dance and compelling theatrical effects. Menacing whispers, fears and enigmas inhabit this dark universe.

Eight dancers began in a line and moved slowly forward to the pulsating dance beats and electronic sharpness of Seed/Stem/Calyx, by Colette Anderson with New York band the Bengsons. Each step, heavy with intensity, hit the audience like a wave. The imposing Abel Rojo stood apart from the line to suddenly crumble, as if in the presence of an invisible enemy that loomed above. Through the reactions of the other dancers, that enemy became real; they looked up with pain, dodged to avoid being hit and crouched in panic.

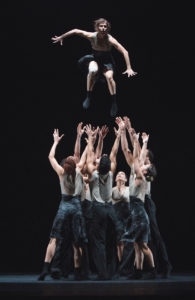

The dancers form relationships that forebode potential violence. In one instance, three male dancers pulled and pushed Acosta, suggesting assault. Instead, one of the men was gently lifted high above by the group. At the end, the dancers clustered. Holding their heads at varied angles, they looked to the sky in terror.

With their suggestive miming and outstanding technique, the dancers held our attention with a choreography that suspends viewers in raw emotions without the need for narrative explanation.

The evening’s final piece, Tabula Rasa (1986) by Ohad Naharin, the former artistic director of Israel’s Batsheva Dance Company, is choreographed to Arvo Pärt’s composition of the same title. Both choreography and music balance energy with quietness.

The work exploded with breathtaking physicality as the nine dancers threw themselves into powerful grand jetés, ran with vitality across the stage and reached out with abandon toward the audience. As this initial fervour evaporated, the breathing of the still audience was reflected in the dancers’ hypnotic placidity. Standing in a line upstage, they stepped in synchronicity exceedingly slowly to the right. This pursuit of the stillness of breath within a subtle motion was poignant, but the minimal choreography weakened the passage. The dancers, however, interpreted this shift from exuberance to calm with magnificent allure.

Where the choreography falls short in each piece, the virtuosity of the dancers took over. Each artist could be a soloist or principal, but they all came together as one ensemble to create a sensational performance.

— SHEENAGH PIETROBRUNO

DI SUMMER 2019

Photo: Rose Eichenbaum