Traces of Montreal Dance: Daniel Soulières steps down from Danse-Cité

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Traces of Montreal Dance: Daniel Soulières steps down from Danse-Cité

By Victor Swoboda

A few months after his 70th birthday in February 2020, Daniel Soulières stepped down from Danse-Cité, the Montreal contemporary-dance production house that he founded in 1982. Some 400 people sent congratulatory messages reflecting admiration for Soulières as a driving force in staging contemporary dance, as a dancer and as a teacher. Undoubtedly many well-wishers — choreographers, dancers, technicians — had benefited at one time or another from his intense interest in their Danse-Cité projects.

Montreal-born Soulières had a family-oriented upbringing with many relatives as playmates. Soulières was six when his father, an amateur actor and occasional theatre producer, died, and it’s tempting to speculate that he unconsciously carried on his father’s spirit. A somewhat chubby teen interested in books, “I changed my body shape toward the end of adolescence, which intrigued me,” he said in a recent interview at Danse-Cite’s downtown offices.

Soulières discovered dance during his two pre-college years at Cégep Maisonneuve where Françoise Graham was teaching Martha Graham technique as part of a physical education program. At Université de Québec à Montréal, he majored in psychology because “psychology and human behaviour interested me. I felt my best quality was empathy. And I did a lot of research on body perception.” At the same time, he continued training in Graham technique, with dancer Jacques Hernez Plessis at Le Groupe Nouvelle Aire, a pioneer contemporary dance company. “I always liked Graham technique,” he says. “It’s a bit like tai chi, which I did later. The emphasis was on breathing, which other techniques didn’t mention directly.”

In 1971, Soulières found a paying job that enhanced his dance education — ushering at Place des Arts, Montreal’s largest theatre complex, where he continued to work up to the present day. It was a unique opportunity for a dancer to observe many international stars and big companies perform. “In 1974, I saw Baryshnikov dance a week before he defected in Toronto.”

Soulières performed with Nouvelle Aire at home and on tour to New York, a city he visited regularly in the 1970s for two-week periods of dance classes. “Whenever I returned from New York, I was energized for six months. Meredith Monk, Cunningham, Graham, Louis Falco — Montreal didn’t have this level of quality.”

In the 1970s, Nouvelle Aire and Le Groupe de la Place Royale were just starting to introduce contemporary dance to Montreal. There were no dance presenters or festivals and little infrastructure. Apart from a few earlier-generation figures like Françoise Sullivan, with whom Soulières made his first foreign tour to Italy, Quebec had no history of homegrown contemporary dance. The city’s two established companies, Les Ballets Jazz de Montréal and Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, were working in more traditional veins than those of the artists whom Soulières was admiring in New York.

A turning point in Soulières’ life came in 1980. Soulières organized a show for himself and dancer Monique Giard called Treize chorégraphes pour deux danseurs, with works by 13 different invited choreographers.

“We did one month of shows in a small 100-seat theatre in downtown Montreal, and each was sold out. I saw that contemporary dance could function in small theatres. And performing the same work many times gave dancers time to examine the work deeply and grow as artists.”

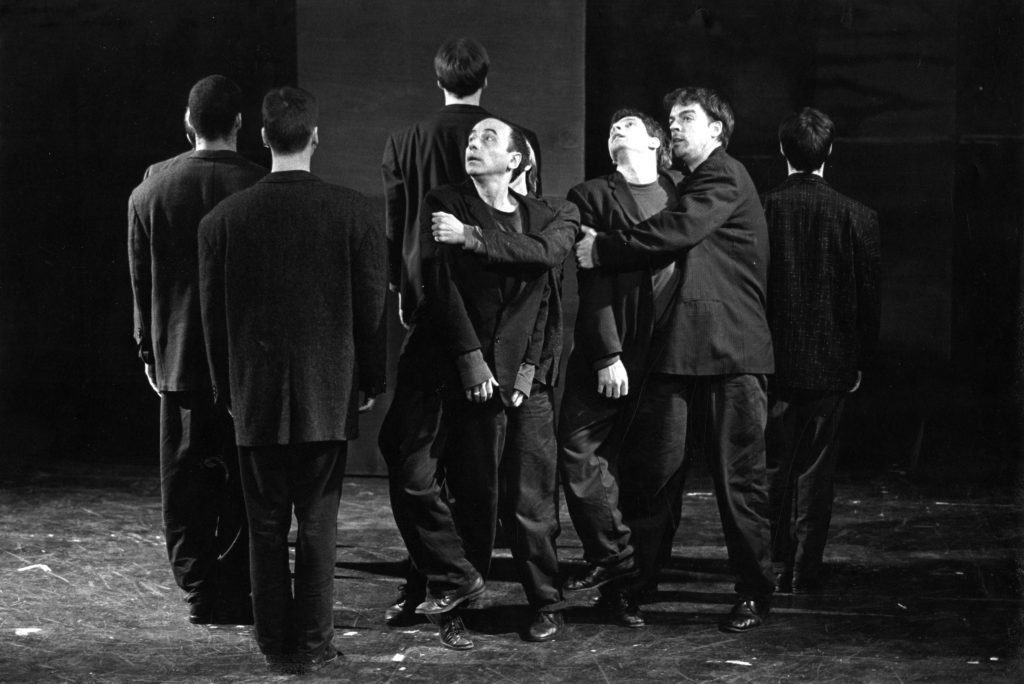

Treize chorégraphes included the first choreography by a young Ginette Laurin, who forged an international career with her O Vertigo company and with whom Soulières often danced onstage. Noteworthy, too, was Soulières’ first professional encounter with another young choreographer, Jean-Pierre Perreault, who later employed Soulières as a soloist in many major works, most famously in Joe, where 32 dancers dressed in floppy hats, raincoats and boots stomped in unison in front of a steep ramp.

“My character was fighting for his own personality,” he says about Joe. “Everyone climbed the ramp looking for a better life but slid down each time. It was a bit pessimistic, so Jean-Pierre changed the end and had me lead another dancer off stage.”

Soulières was not alone in seeking to build a contemporary dance infrastructure. In 1981, Dena Davida opened her first season at a new contemporary dance venue, Tangente. That season included Quatuor d’improvisation en danse et en musique (QUIDAM), a work jointly created by Soulières and Giard with musicians Robert Gélinas and Jean Dérome.

The experience of working on QUIDAM and Treize chorégraphes encouraged Soulières to create Danse-Cité, a forum where several creative voices had a say in staging work.

In February 1983, Danse-Cité opened its first season beginning with Giard and Soulières in Les événements de la pleine lune, which had grown out of the improvisatory approach seen in QUIDAM. The season continued with three other works, one by Perreault, another by Giard/Soulières, and a joint work by Perreault, Soulières, Laurin and Louise Bédard. Intentionally, Danse-Cité staged few shows a year.

“Daniel had four or five shows annually, whereas I was presenting up to 30 weeks of dance,” recalls Davida. “He was very selective.”

Back then, contemporary dance was largely choreographer-centred. Soulières made the dancer the central creative figure. “He gave dancers a lot of autonomy and agency. That was one of his great innovations — allowing a dancer to forge a project, hire a choreographer, choose a lighting designer,” says Davida.

Marc Boivin, for years one of Montreal’s most in-demand dancers, staged two Danse-Cité projects. “Daniel understood people’s ideas and would say yes to them and then figure how to make them work,” recalls Boivin. “Sometimes Daniel attended rehearsals, listening, watching, taking it in, but I don’t remember feeling like he was a producer checking the work. He was there to solve artistic or logistical problems. If asked, he gave feedback.”

Davida sees Soulières as an innovative curator. “He put forward a whole framework about dance in unusual spaces and events where spectators wandered from room to room. And he used contact improvisation when few were interested in it.”

Soulières eventually introduced the series, Traces chorégraphes, featuring a single choreographer, for the European market. “Creating a mixed program of 20-minute works was stimulating because it allowed for a large range of styles,” he says, “But Europeans wanted one work on the bill so Traces chorégraphes featured a longer work by one choreographer.”

Throughout the Danse-Cité years, Soulières danced in his own productions and others’. He projected a powerful stage presence without flash or virtuosity.

“It was a pleasure to share the stage with him,” recalls one of Soulières’ contemporaries, the dancer-choreographer Sylvain Emard. “I never saw him angry about his performance. I never saw him frustrated. Each performance was a lesson in how to create.”

Long-time Danse-Cité administrator and Soulières’ successor, Sophie Corriveau, says he put his ego aside when learning a role. “After rehearsals, he wrote his thoughts about interpretation and how he felt in notebooks. That really struck me.” Corriveau admits that Soulières was “not an ace accountant, but he always took care to stay within budget and never put the company at financial risk. He was ready to adapt but stubborn about his core values.”

At 70, Soulières is looking for a new training regime and preparing for a role in a new dance show, explaining, “I want to continue dancing and not get flabby.”