D-Man in the Waters: Relevant during AIDS, still resonant today

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- D-Man in the Waters: Relevant during AIDS, still resonant today

By Nadine Matthews

At the height of the AIDS epidemic, two beloved members of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company passed away from the deadly virus in the space of just two years. Arnie Zane, the dance company’s co-founder, died in 1988 and Demian Acquavella, a uniquely spirited dancer, in 1990.

In early 1989, the company’s other co-founder (and Zane’s life partner), Bill T. Jones, was commissioned to choreograph a work to the first movement of Felix Mendelssohn’s Octet for Strings in E-Flat Major. Jones used the opportunity to address the grief, loss and existential fear shared by many in the dance community at that time, creating a now canonical work, D-Man in the Waters. The D-Man of the title is the affectionate sobriquet bestowed on Acquavella by Jones and the other members of the company.

In 2020, at the height of the COVID epidemic, a documentary about that dance, which former company member Rosalynde LeBlanc had been working on since 2012, hit the film festival circuit. Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters, directed by LeBlanc and Tom Hurwitz, chronicles the story behind the creation of D-Man in the Waters, and LeBlanc’s recent efforts to teach the emotionally and physically gruelling choreography to a new generation of dancers.

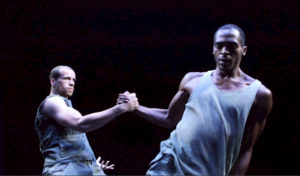

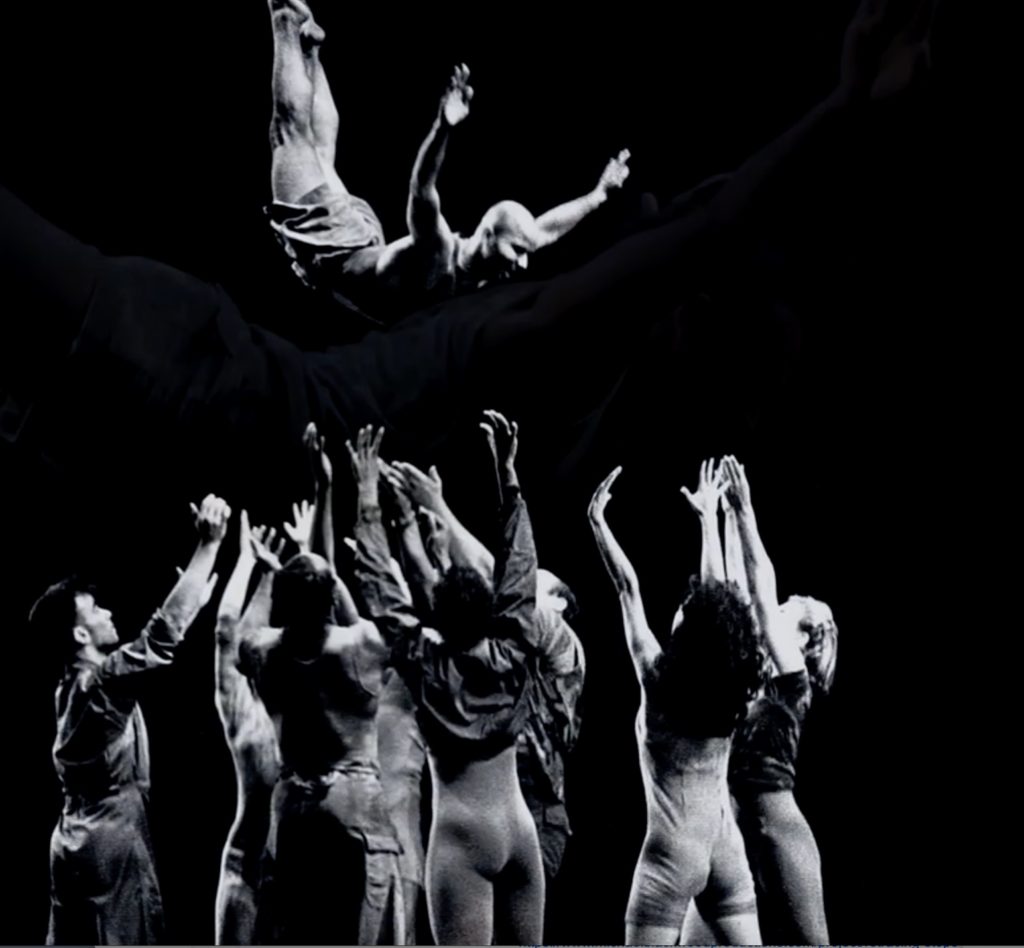

D-Man in the Waters is a buoyant celebration of how deep respect for life can manifest in a fighting spirit. Dancers costumed in military fatigues perform feats of athleticism, marked by expansive gestures. Dramatizing the energy, skill and resilience needed to survive the fearsome power of the ocean — or of a potentially fatal virus — D-Man in the Waters is replete with running, jumping and diving, in kinetic elegance.

Communal spirit is communicated throughout the piece. The dancers grasp each other. They jump into each other’s arms without hesitation. They stand on one another’s backs. They carry each other.

In a press release, LeBlanc talked about one of the factors that drove her to make the film: “The absence of AIDS from current political and social discourse in [the United States] has left successive generations without any way to contextualize the spirit and intensity of the art made in response to it.”

When we spoke by phone in early December, Jones admitted he was “very touched” when he learned LeBlanc was making the documentary. “I have great affection for Roz, who came to my company when she was only 19.”

At the time he was creating D-Man in the Waters, Jones recalls seeing, “a lot of heroism on the part of ACT UP [AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power] and groups like that. For the art world it was a learning curve. At first they thought [AIDS] had little to do with them; and then it became apparent [it did].” ACT UP was founded in the US in 1987 to raise awareness about a mystery disease that often strangled and snuffed out life in a short space of time, at a period when the government seemed indifferent to the AIDS crisis.

According to the HIV Insite website run by the University of California San Francisco, in 1983 “men who have sex with men” accounted for about 71 percent of deaths from infection by HIV (the virus that causes AIDS), leading to some calling it “the gay plague.”

Prominent American evangelical preachers such as Jerry Falwell linked AIDS to homosexuality as a punishment from God. Falwell famously stated, “AIDS is not just God’s punishment for homosexuals, it is God’s punishment for the society that tolerates homosexuals.”

Closer to home, Jones remembers the response of family and members of his community to news of AIDS. “There are Christian fundamentalists in my family and people were gossiping. ‘So and so has this thing…”

Today, quarantined at home in a New York City suburb, Jones feels the threat from COVID less acutely than he did from AIDS. “Back then, we were literally wondering if we would make it to our next season at the Joyce Theater. We were literally that unsure. It was like, ‘We’re all gonna die.’”

In my recent telephone interview with LeBlanc, she recalled the complex zeitgeist at the time she moved to New York City in 1993 to become a member of the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company. That year, according to records from the US Center for Disease Control, “HIV infection became the most common cause of death among persons aged 25-44 years.”

“There were two opposing forces,” recalls LeBlanc. “Heartbreaking melancholia. Then, an upsurge of mobilization, people saying, ‘We have to do something’.” It also felt important, she said, to not take relationships or time for granted. “You didn’t know if that person would be there six months from now.”

That audiences continue to embrace D-Man in the Waters heartens Jones, and LeBlanc’s film opened his eyes to the relationship that many of his dancers have to the piece. “I didn’t know Roz or any of them had a deep attachment to that particular work, and to the moment which it was made,” he says.

In the film, LeBlanc and Jones are seen coaching the mostly still novice dancers how to connect emotionally to a work rooted in a particular historical moment. Interrogating the work beyond the technical aspects, Jones hints during our interview, brings intricate pieces such as D-Man in the Waters to fullness. “What is there in your world right now that galvanizes you the way that moment galvanized us?” he asks, explaining the thought process behind how LeBlanc trained the new dancers. “You just have to give it everything you have athletically, technically, and then you pray for that extra dimension. Can you bring it? Can you bring the spirit into the room?”

When our interview once again turned to the topic of COVID, Jones discussed how the pandemic attacks and undermines the creative process itself. “Dance is a social art form,” he says, “with real people in real time in real space with real sweat and real gravity among other real people who are there to witness. It’s a communal act. COVID has made that a perverse, almost unattainable goal.”