Musical Choices: Four master choreographers share their inspiration

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- Musical Choices: Four master choreographers share their inspiration

By Elaine Gaertner

A musical composition can support the muscular energy of movement; guide the tempo, flow and dynamics of a dancer; accompany a narrative in a cinematic way; or float on top of visual imagery, allowing synergy to develop without design. All these approaches can result in works of dance that are eloquent and imaginative, as it does for the four choreographers interviewed below — Hans van Manen, Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, Mark Morris and Marie Chouinard. Whether the music is the initial inspiration for choreography, or composed after a storyline or movements are established, dance and music have an intimate relationship in the works of this accomplished quartet of dancemakers.

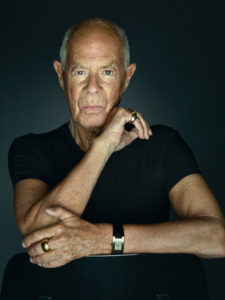

Hans van Manen

At the age of 88, Dutch-born Hans van Manen has choreographed more than 120 ballets over more than six decades. His works have been performed by companies across Europe and North America, including Stuttgart Ballet, London’s Royal Ballet, Royal Danish Ballet, Houston Ballet and the National Ballet of Canada, as well as at home in the Netherlands by Dutch National Ballet and Nederlands Dans Theater.

An older brother who played the piano was a pivotal influence during his childhood; van Manen listened to him practice with rapt attention for many hours each day. When we spoke earlier this year over the phone, he acknowledged this experience as being responsible for “an affinity for the sound of the piano” as well as for his “sensitivity to music.”

Little wonder, then, that so many of his pieces were choreographed to solo piano, written by an exhaustive list of composers that includes Beethoven, Bach, Satie, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Debussy, Rachmaninov, Rossini, Janáček and Prokofiev. The rapport that can be created between a live pianist and dancers is important to him, as is the practical issue of being able to hire one musician versus a whole orchestra for performances. Certainly, even a solo piano score can express a wide palette of colours and dynamics, and with the nuanced touch of expert fingers on a keyboard, be an equal partner to the creations of this doyen of choreography.

Van Manen’s emphasis has always been on choosing what he described as “good” music. By this he means “music of significance,” and that “the composer has put a lot of thought into the composition.” Music is the starting point for all his pieces, the inspiration that propels his creativity and thought process throughout the development of a work. His approach to choreography shuns “too much movement” within each beat as he regards it as “extraneous.” Instead, he choreographs with a measured restraint that embodies the essence of the chosen music.

An admirer of George Balanchine, van Manen echoed the Russian-American choreographer’s famous statement about “seeing the music and hearing the dance.” He also offered his own unique insights into the relationship between the two art forms. “Rhythm is like the floor of the dancers,” he said, explaining that both the music and movements flow from a similar unending motion.

Despite his prodigious body of work, long career and considerable contribution to dance, he spoke with great humility during our interview. Every mention of music evoked a palpable excitement in van Manen’s voice, a reflection of his reverence for composers and musicians who are an inseparable component of his creations.

Annabelle Lopez Ochoa

Annabelle Lopez Ochoa started her career as a choreographer in 2003. Since then, her works have been performed around the globe by, at last count, 65 ballet companies. Her musical insights give her approach a depth and varied musical perspectives that draw from classical, popular and contemporary music as well as jazz.

Born in Belgium in 1973, in her youth Lopez Ochoa studied solfège (sight-singing music) and recorder for six years, and piano for a year; she also participated in rhythm classes at Antwerp’s Royal Ballet School. She says that her understanding of music further “deepened” when she danced as a member of Djazzex, a company founded in Holland in 1983. There, the dancers improvised to the music of live jazz musicians as part of their performances, an experience that made her “more aware of all the layers of musical composition.” On a personal note, Lopez Ochoa spoke of “having my eyes opened about how to listen to music” owing to her relationships with a jazz pianist and a conductor.

Although music is the starting point for much of her work, the exceptions are narrative pieces, where “the script is written and thought out before the music is composed.” English composer Peter Salem has collaborated on many of these narrative works, including Broken Wings (2016) and Frida (2019).

“The mood, the rhythm and the colour” of the music are her criteria for choosing music for abstract choreographies. These have been set to Schubert, Vivaldi, Bach, Tchaikovsky, Beethoven, Philip Glass and Max Richter. Other times, her abstract works have been set to the scores of an eclectic mix of composers, including Domingo Gura (an Argentinian percussionist), Jean-Philippe Goude (a contemporary French film composer), Veljo Tormis (a modern Estonian composer), as well as Steve Reich’s iconic Clapping Music and compositions by Richter and Rachmaninov. Music from all of these composers is integrated into her piece Agua Viva (2018). This musical approach allows a work to be shaped by a progression of choreographic ideas matched to a variety of music, rather than being constrained by a single composition.

Indicating the importance of the music, Lopez Ochoa remarked that when she creates an abstract piece, “the music will be the driving force of the ballet.” She imaginatively refers to music and dance as a “married couple,” noting that “depending on the moment or needs in the ballet, one of them will make concessions for the other to shine.”

Mark Morris

Mark Morris was born in Seattle, Washington, in 1956; by 1980 he had founded his own dance company. He has often been called the most music-centric choreographer of his time and compared to Balanchine, who studied piano and advanced composition at a music conservatory. Morris’ formal musical training includes basic theory, solfège and music history; his musical erudition has enabled him to conduct orchestras, and direct operas and music festivals. Yet he cites his “love” and “passionate lifelong interest in music” as having the greatest influence on his choreography above any formal training.

Morris’ criteria for choosing music is that it be “engaging and have an element of surprise.” He avoids music specifically written for dance (with several exceptions) and prefers music that has odd lengths of phrases, unusual instrumentation and a complex rhythmic structure “bordering on incomprehensible.” A prime example is his piece Numerator (2017), one of seven choreographed to the music of American composer Lou Harrison. Numerator’s score, titled Varied Trio for violin, piano, and percussion, brims with Morris’ preferences: percussion instruments from non-western cultures, which can sound unfamiliar to western audiences; uneven phrases; and a rhythmic structure that defies counting. Another example would be Morris’ Pure Dance Items (2016) to composer Terry Riley’s Salome Dances for Peace, a mixture of jazz, blues, North Indian raga and Middle Eastern scales.

A favourite historical era is the Baroque; Morris has created works to the music of well-known Baroque composers Purcell, Bach, Gluck and Handel. Among 20th-century composers, he has choreographed to Hindemith, Stravinsky, Satie, Bartok and Ives, among many others. Each of these compositions speak to his passion for using music so that its elements intersect with the choreography in a way that illuminates and enhances the impact of the music.

Piano, vocal and chamber music are among Morris’ musical preferences because of the small number of musicians involved, an important consideration in live performance. Musicians are always an integral part of his pieces; he calls them “equal partners” with the dancers. In fact, he doesn’t permit his work to be performed without live musicians, a testament to his vehement convictions about the importance of music and musicians in dance.

Choreography should not be about “musical pandering”; nor should it be a “literal translation” of the music. These beliefs of Morris are evident in the complexity of his musical choices and in his translation of the most intricate of music into movement that transforms the “incomprehensible” into accessible and coherent choreographic works that can be enjoyed by his audiences.

Marie Chouinard

Marie Chouinard, born in Quebec City in 1955, created her first choreography in 1978 and founded her own company in 1990. Her work intertwines multiple art forms, including dance, theatre, voice, technological innovation, poetry and visual art. When she spoke with me over the phone from her home in Montreal, our conversation revealed how music is interwoven into all of these elements and the role it plays in her creative process.

Chouinard is a highly idiosyncratic and inventive artist, both in the way she uses music and in the creation of her multi-layered choreographic work. Often she choreographs movements before she adds an original musical score written specifically for the piece. She has also choreographed to the existing music of mainstream composers; this, she explained, was when she was passionately drawn to specific compositions and felt an artistic “imperative” to do so, feeling herself almost in a state of creative “emergency.” These scores include Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun (1987), Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1993) and Bach’s Goldberg Variations (2005).

Since 1996, she has often collaborated with Louis Dufort, known for his electroacoustic compositions, generated by both technology and acoustic instruments. Some of their collaborations include Le cri du monde (2000), Chorale (2003), Henri Michaux: Mouvements (2011) and Hieronymus Bosch: The Garden of Earthly Delights (2016), performed at preeminent dance festivals in Europe and Canada.

Music has a uniquely personal context in her choreography, beyond being just a structured, codified language of expression that serves as a guide for movement. It is just one of a multitude of visual and auditory layers in her pieces, an entity integrated into the totality of each work. Her creations utilize the music in an unconventional fashion, her movements following, as she puts it, an “intuitive” grasp of the score, an “instinctual” and “organic” way of integrating the elements of music.

Chouinard characterizes her reaction to music as “visceral, not cerebral.” Music, she says, has the capacity to “make the vertebrae in my spine vibrate.”