By Elaine Gaertner

Vaslav Nijinsky wrote in his diary, “Applause is not opinion. Applause is a feeling of love for the artist.” The following four artists — Muriel Valtat, Andrea Boardman, Gaby Baars, and José Manuel Carreño — have felt this love, a palpable embrace from audiences around the world. Today they have abandoned the spotlight to devote themselves to teaching aspiring dancers at L’École supérieure de ballet du Québec.

Two were aware of their desire to teach since their earliest days as performers, while the other two came to the realization later in their careers. All four cited an excellent ballet education and influential teacher/mentors as their fountains of inspiration. Each strives to to be a “2.0” version of former teachers, passing on all they have learned, danced, and experienced.

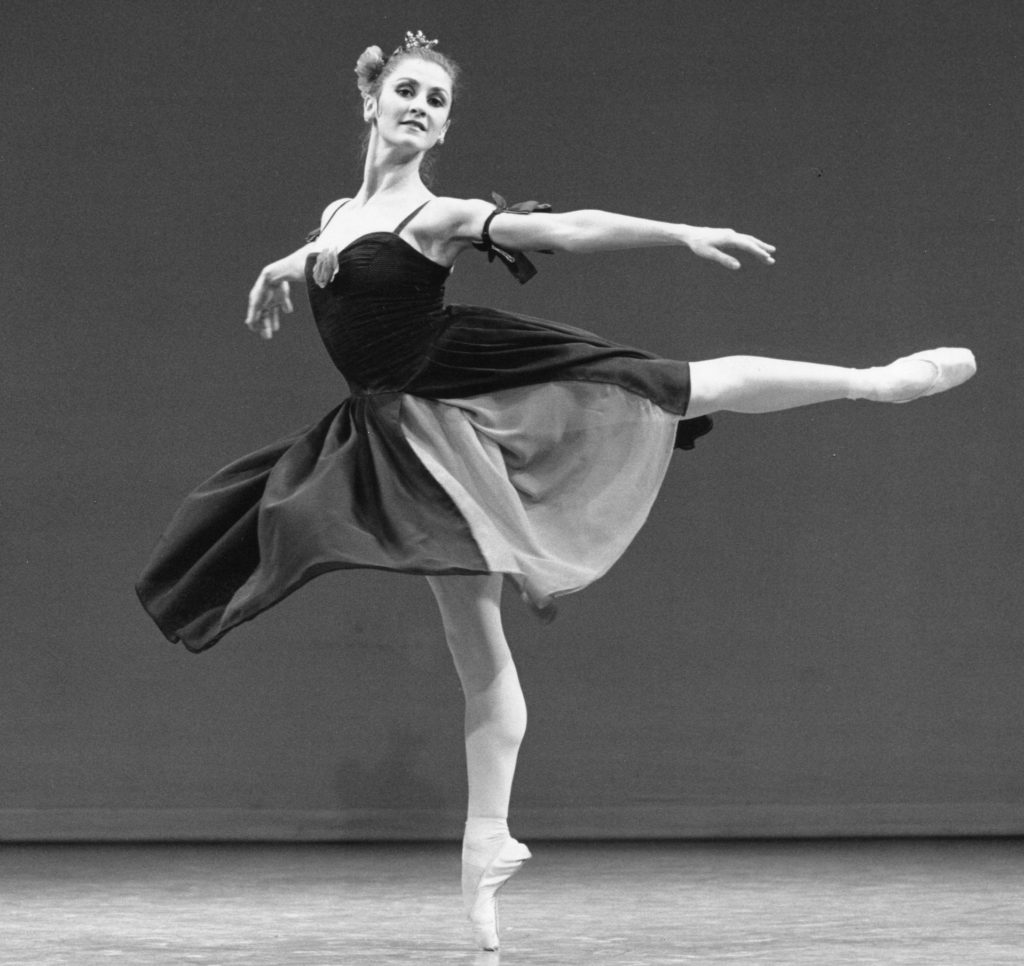

MURIEL VALTAT

Born in France, Muriel Valtat studied ballet until age 17 with teacher, actress, and mentor Yvonne Cartier, a former dancer with London’s Royal Ballet. Valtat subsequently used prize money from competitions and scholarships to attend the Royal Academy of Dance and the Royal Ballet School. Upon graduation, she was offered a contract with the Royal Ballet, rising to first soloist in 1994.

Before the birth of her second child, Valtat decided to seek a teaching diploma from the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing. “I knew I wouldn’t go any further [as a dancer] — and my career had been beautiful,” she says. “I wanted to have an equally satisfying second career as a teacher without the stress of injuries.”

In addition to the detailed Royal Academy of Dance syllabus that she learned as a child, Danish, Russian, and French teachers from her days as a dancer with the Royal Ballet have all influenced her teaching. “I valued the potential of each of their methods. I tried to be open and to absorb all of their styles.” This was the platform upon which she embarked as a teacher.

In 2004, she was hired by L’École supérieure de ballet du Québec. “I had to dive into the deep end of teaching. It can’t be learned from a book. You have to find your own way and it takes at least 10 years to become comfortable,” she admits. She now teaches ballet, pointe, and variations to students of many levels, from ages 12 to 20.

“Seventeen years later, I have found my method. I am so at ease — even though I continually question and still have doubts at times.” To enrich herself, she began studying the Cecchetti Canada method in earnest and has earned multiple higher diplomas. “Cecchetti helps me to cover the spectrum of steps. But in other ways, I feel like a doctor — I diagnose based on what I see at the moment. Each student is like a patient.”

Valtat spoke with conviction when she said, “I love my art form. It is a passion. I think communicating this passion, sharing the essence of this art with honesty and humility, is what validates me now. I used to miss performing, but now I’ve moved past it with my teaching and studying. I’m putting on weight but I don’t care anymore!”

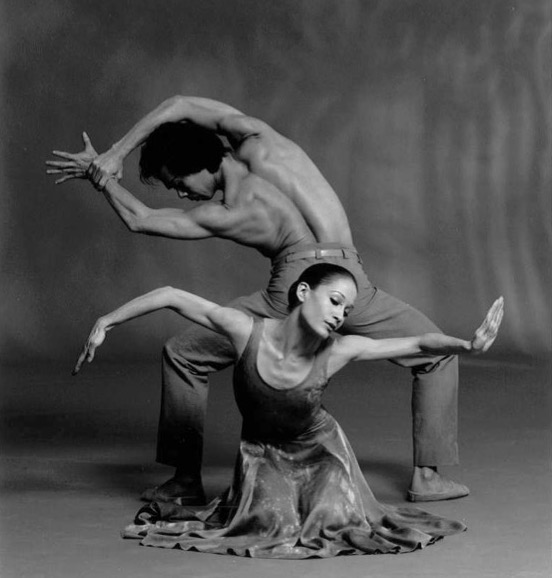

ANDREA BOARDMAN

Born in the United States, Andrea Boardman’s mother was Japanese, her father originally from England. She now considers herself a Canadian, a citizen for more than 40 years. She trained at the Academy of Arts in Champagne, Illinois, and at 18 was hired by American Ballet Theatre Repertory Company, now the ABT Studio Company.

At the end of her tenure, American Ballet Theatre’s then-artistic director Mikhail Baryshnikov told her she was not good enough to be a soloist and was too short to be in the corps de ballet. In 1980, despite his dire predictions, Boardman was hired as a demi-soloist with Les Grands Ballets Canadiens in Montreal. She was soon promoted to soloist and later principal dancer. She left the company in 2001, at which time she joined La La La Human Steps. Her retirement from the stage in 2009, at age 49, was the beginning of a new career as a mentor and educator.

Boardman had always enjoyed teaching roles such as her solo in Nacho Duato’s Na Floresta. “I was amazed how much I enjoyed the process of sharing the steps, technique, musicality, quality, imagery, all the information Nacho had imparted to me. I really wanted to pass it on,” she says. This experience wrote the script for the next phase of life that would involve sharing her wealth of knowledge with young dancers.

In 2010, to prepare for teaching at L’École supérieure, she enrolled in the school’s Teacher Training Program, which included courses in anatomy, pedagogy, psychology, and music. Lawrence Rhodes, former director of Les Grands Ballets Canadiens and New York’s Juilliard School, was another influence on her teaching. “He opened my eyes to a heightened consciousness of the opposition of energy and lifting off the spine to allow for greater range of movement.” Today, in addition to teaching college level classes at L’École supérieure, Boardman directs their college program.

Nothing can replace the satisfaction of performing for Boardman, physically, emotionally, or spiritually. She has, however, found tremendous fulfillment in seeing her students evolve. “I give them my heart and soul,” she explains with characteristic warmth. “They respond with progress and success. It’s a wonderful cycle of reciprocation.”

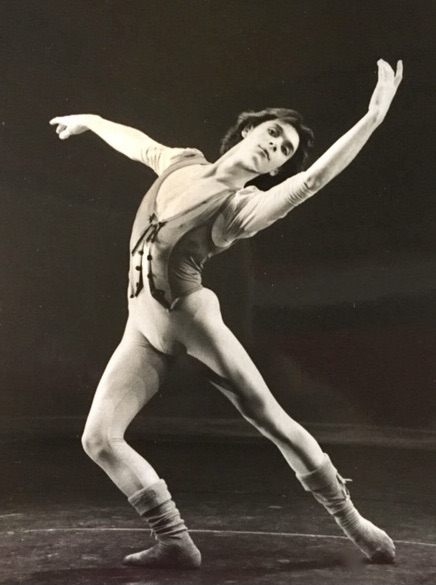

GABY BAARS

Dutch-born Gaby Baars trained at the Nels Roos Academy (later the National Ballet Academy of Amsterdam) until the age of 18. During his last year at school, which found him bored and impatient, the director of Dutch National Ballet offered him a contract upon graduation. “Not soon enough!” says Baars. “Jirí Kylián offered me an immediate contract with Nederlands Dans Theater while I finished the school year.”

Baars stayed with NDT for several seasons, then sought a new challenge with Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo. At the age of 25, he decided to take a break from performing, citing injuries, mental burnout, and fatigue from travelling. For two years, he taught at the Princess Grace Academy (directed by Russian ballerina Marika Besobrasova) associated with Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo. Thus began his first experiences as a teacher, choreographer, and mentor to younger dancers. He admitted there was always a part of him that preferred to be behind the scenes.

He would later return to performing with the company, and become the assistant to artistic director Jean-Chrisophe Maillot. After 14 years, he moved to Montreal, where he now teaches for L’École supérieure’s upper divisions of high school and college students.

An autodidact thrust into teaching at a young age, Baars drew upon his experiences as a student who had been taught versions of both Vaganova and Cecchetti methods.“I have no regrets in not having had any formal teacher training,” he says. “Within my life experiences, working with hundreds of dancers and teachers, exposure to a diversity of training and approaches has been my formation.”

One teacher who marked him, both positively and negatively, was Truman Finney, an iconic international ballet pedagogue. It began with dislike for Finney’s need to absolutely control the dancers, his minimalist musical approach (obliging the pianists to play just an occasional “pling” followed by a long silence), and his deceptively simple but tortuous class. Later, this dislike turned to respect and admiration because of how Finney’s class improved strength and technique. “I forced myself to absorb his style, his approach, and his depth of knowledge.”

Baars’ own teaching is focused on making dancers adaptable to all situations, touching on a wide range of styles and vocabulary within the classwork. He strives to be approachable and understanding, knowing each individual physically and psychologically, a bit of a departure from his own training. “This is as important to me as the class material,” he says.

When asked to compare the joy of performing to teaching, he admits, “I never cried after a performance. Last month, I cried when the girls in my class gave me cards of appreciation. Teaching has become richer than performing for me.”

JOSÉ MANUEL CARREÑO

Born in Cuba, and now a dual Cuban-US citizen, José Manuel Carreño attended the Cuban National Ballet School until graduation at 18. His first contract in the corps de ballet with the Cuban National Ballet lasted four years, after which his prodigious talent propelled him to the position of principal dancer, first with with English National Ballet and then the Royal Ballet in London. In 1995, he was lured away to join American Ballet Theatre, where he stayed until his retirement from the stage in 2011.

Carreño’s greatest influences are his teachers from the Cuban National Ballet School and company, especially Loipa Araújo and his uncle, Lazaro Carreño. “I think they were the best teachers around at that time,” he proclaims proudly. He also considers German-American ballet master Willy Burmann and Russian ballerina Irina Kolpakova, teachers and coaches from his days with ABT, as precious contributors to his evolution as both a dancer and teacher.

“Every time we perform, we have to warm up, we have to teach ourselves: this was my first experience teaching,” he says. “In my culture, teaching is very natural. My uncle, for example, taught in the school and company while still dancing. So many principal dancers taught during their career. From the beginning of performing, I saw the process of passing on my knowledge as my future.”

Carreño was invited to dance in companies around the world and was often asked to guest teach in foreign schools. “In Italy, Cuba, Japan, I felt prepared to teach what I had learned. I didn’t follow any particular method. The Cuban school was influenced by the Vaganova method, but now is considered its own method.” He confidently states that the class he teaches is as international as his knowledge. “I have been exposed to teachers from all countries and have worked with so many legends of the ballet — Anthony Dowell and Natalia Makarova, for example. Knowledge is the key to being a good teacher. Anyone can make up combinations; what I focus on is the quality of execution for the stage.”

Since 2020, Carreño has taught both high school and college students at L’École supérieure. “I definitely miss my fans, my audience, and the dancing. Teaching replaces this for me,” he explains. He was told by former ABT partner and ballet mistress Susan Jaffe that he would only realize how much he knew once he stopped dancing. “I feel as though I know almost everything now,” he declares sheepishly.

Elaine Gaertner has been on the faculty of L’École supérieure de ballet du Québec since 1986, where she teaches courses in music for ballet teachers.