Vancouver: Revealing new rep from Ballet BC, and festival season

- Home

- City Reports 2020 - 2023

- Vancouver: Revealing new rep from Ballet BC, and festival season

By Kaija Pepper

Crystal Pite’s The Statement does exactly as the title says: it makes a statement. And it’s a big one, about conflict and boardroom politics, and about guilt in the lower ranks for not calling out the wheelers and dealers who put their dangerous spin on things. Given the current Russian invasion into Ukraine, the work for four dancers and four actors (heard only in voice over) carried an extra punch. Ballet BC nailed it on March 3, the opening night of their latest mixed bill at home at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre.

In The Statement, which Nederlands Dans Theater premiered in 2016, the Vancouver choreographer has again made movement to text like no other. Each dancer reveals their character’s innermost self, adding layers of human complexity that teases out subtext — comedy and tragedy — in Jonathon Young’s script. Anna Bekirova, Miriam Gittens, Justin Rapaport, and Rae Srivastava posed and postured with uncanny precision around a large boardroom table, a staging that evokes the iconic anti-war ballet by Kurt Jooss, The Green Table (1932).

Germany’s Marco Goecke opened the triple bill with his Woke Up Blind, another 2016 NDT premiere. Set to haunting and intense vocals by the late Jeff Buckley, the seven dancers were equally intense, with quirky, jerky gestures that seemed to this viewer unrelated to heart-stabbing songs about troubled love. Yet the movement — arms held at odd angles, hands that flutter and jab, torsos that convulse — had its own muscular charm.

Ballet BC artistic director Medhi Walerski’s just BEFORE right AFTER, which premiered in Luxembourg last month, sent the audience home happy. The beautifully staged work for 19 dancers (17 on opening night due to illness and injury) gave all of the mostly very young company members and apprentices a chance to perform as a team. Kiana Jung got things started, alone downstage centre, with her elegantly curved body and careful unfurling of limbs. The others are slowly revealed behind a dark scrim, standing close together, waiting their moment.

Earlier in the season, January’s PuSh festival brought another, more direct, statement piece: Joseph Toonga’s defiant Born to Manifest, about his own and others’ experiences growing up as Black British men in East London. Judging from the positive reviews since its 2019 premiere, the 50-minute duet hit a responsive chord with critics. With audiences, too, evident from the enthusiastic applause when I saw it at Performance Works.

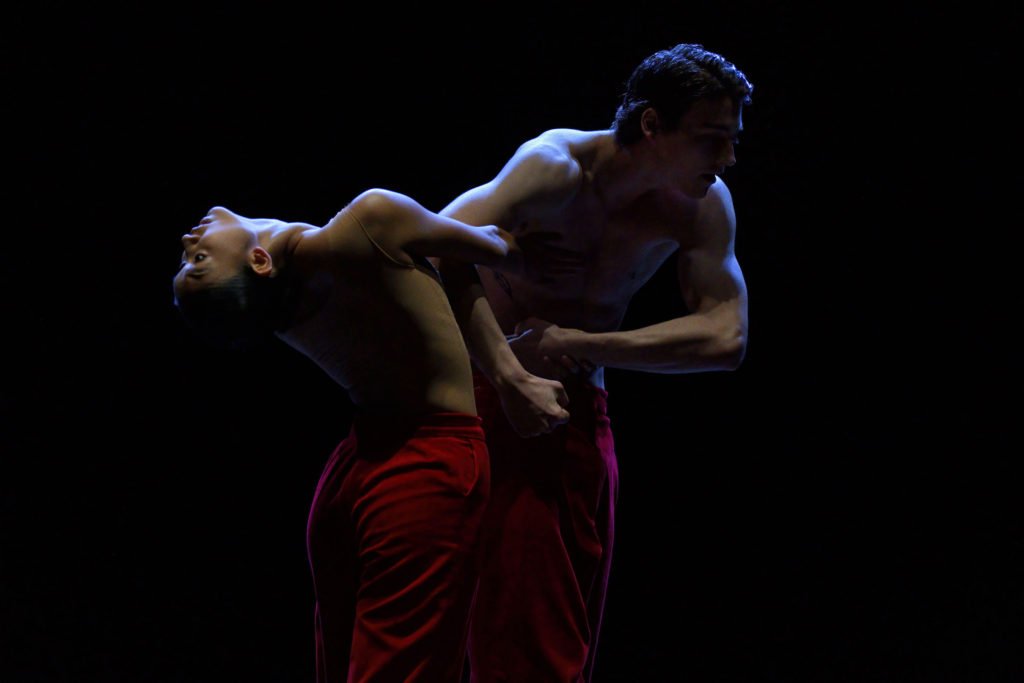

The duet features urban dance styles, including the weighted energy of krumping and the more established form of popping, in often explosive but tightly contained muscular moves. Performers Toonga and Cache Thake repeatedly spar together, or whoop shrilly while beating their chests, gazing dispassionately at the audience. Or, adding a gentler note, a raised fist is softly clenched. Toonga, the artistic director of Just Us Dance Theatre, founded in 2007, is currently an Emerging Choreographer with London’s Royal Ballet. As part of the two-year program, he will create with the company’s dancers, no doubt an interesting experience for all.

More PuSh dance came from Montreal’s MAYDAY in early February: artistic director Mélanie Demers’ La Goddam Voie Lactée (The Goddam Milky Way) at Scotiabank Dance Centre. The 2021 work for five women with attitude is also, if more whimsically, in your face — they strum electric guitars on a scarlet floor, utter animal cries, and face their audience in a series of exaggerated poses conveying sex, power, or extreme emotion. At times, it was like watching a group of kids playing dress-up with clothing and props found in a theatrical trunk filled with random treasures: a sparkly top, big rubber boots, a hair dryer, a drill. The publicity calls La Goddam Voie Lactée “a secular mass in which our discontents can be expressed,” which sounds about right, though some of the scenarios were too quirky to draw this viewer into any sense of universal ritual. But, for the most part, the 75-minute show was engaging in its constant shifts in scenario, including music (led by singer-songwriter Frannie Holder) and, of course, movement (Stacey Désilier, Misheel Ganbold, Chi Long, and Léa Noblet Di Ziranaldi).

It was a season of festivals, continuing in February with the fourth annual Matriarchs Uprising, which aims to bring together “Indigenous women who are nurturing the art of Contemporary Indigenous dance and storytelling.” Aiming also to welcome a wide audience, the atmosphere was casual, with a few cushions on the floor at the one live show, a double bill at Scotiabank Dance Centre. Seating was partially in-the-round, with popular music playing as we entered and at intermission.

Ancestor Dances, a solo by Maura García (non-enrolled Cherokee/Mattamuskeet), featured seven “small dances” based on the stories and movements of seven recently deceased ancestors. These became a dance work of idiosyncratic walks, poses, and gestures, introduced in a voice-over text about the practice of slavery by some members of the Chocktaw Nation in the United States. How this challenging subject matter connected to the dance was unclear to this viewer, but it was a treat to hear the beautiful African-American spiritual, Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, attributed here to a Choctaw freedman.

Before the second piece, Kwê, lead artist Jeanette Kotowich (Nêhiyaw/Métis and mixed settler ancestry), and her collaborating dancer/improvisers Stéphanie Cyr, Olivia Shaffer, and Tamar Zehava Tabori, shared a high-spirited warm-up to club music. The piece itself was somber, set to deep electronic sounds that repeatedly crested and receded, with the dancers engaging with both the music and each other.

Still on the boards and online to March 26: the 22nd annual Vancouver International Dance Festival. Produced and presented by Kokoro Dance’s Barbara Bourget and Jay Hirabayashi, shows can be found in theatres, studios, and homes all over town.