A Balanchine Repetiteur: Joysanne Sidimus shares her passion

- Home

- Features 2020 - 2023

- A Balanchine Repetiteur: Joysanne Sidimus shares her passion

By Elaine Gaertner

For Joysanne Sidimus, the path to becoming a repetiteur for the George Balanchine repertoire began in 1969 while she was a principal dancer with the newly formed Pennsylvania Ballet. That’s when she first staged Serenade, a ballet she had performed numerous times as a corps member with New York City Ballet, and as a principal dancer with the National Ballet of Canada and Pennsylvania Ballet (now called Philadelphia Ballet). “Muscle memory is very reliable and served me well,” she explained when we spoke recently.

Longing for a respite from Pennsylvania Ballet’s gruelling touring schedule, in 1970 she asked Balanchine — who she had known since her student days at the School of American Ballet and then as a member of the corps at NYCB, both institutions led by Balanchine — if she could stage his works for other companies. He agreed, with the caveat that she would observe every company class he taught, and the rehearsals and performances of his ballets, before she began. This turned into nine months of “watching the greatest genius in ballet teach, rehearse, and create,” declared Sidimus (pronounced Si-DEE-muss).

Since Balanchine’s death in 1983 and the 1987 establishment of the Balanchine Trust — responsible for licensing and preserving the artistic integrity of all Balanchine’s works — she has been entrusted with staging 16 different ballets for companies and schools.

In addition to muscle memory, copious notes of every step of the choreography written beside each count of music help Sidimus in the staging. Within the musical score, she makes notations with additional rhythmic detail, an acknowledgement of the close relationship between music and choreography, and evidence of her own musical erudition. Archival videos are merely “helpful” reminders, studied prior to starting but never used in the studio. “A film is only a record of one particular performance and people make mistakes,” she says. She immerses herself in all of these resources months in advance of any engagement.

New York City-born Sidimus, who now lives in a small municipality outside Toronto, has been a member of the artistic staff of the National Ballet of Canada for the past 38 years, responsible for staging the company’s Balanchine repertoire. Her next project with the company will be to stage Symphony in C, set to Bizet, on a triple bill in March 2023, a ballet that represents “the pure joy of dancing to an incredibly danceable score,” says Sidimus.

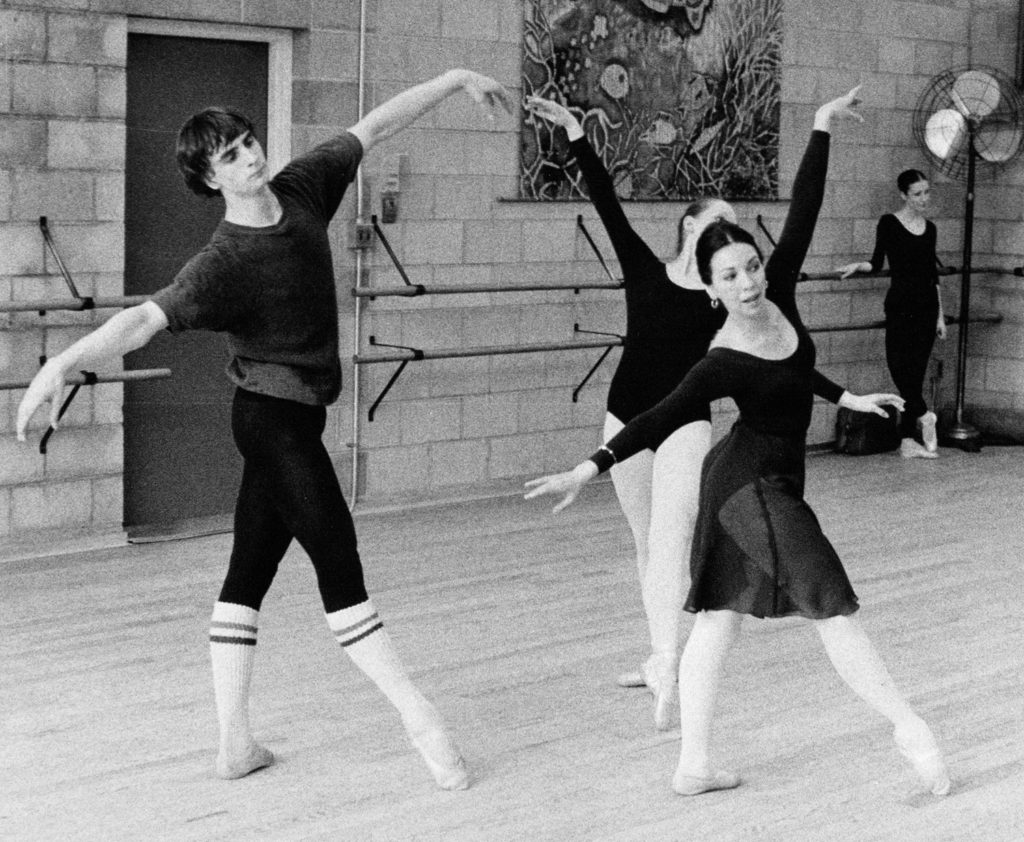

When we spoke, she was in Montreal to stage the first movement of Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco for the École supérieure de ballet du Québec. It is a ballet she has danced as both a corps member and soloist during her professional career. Conceived originally as an exercise for students at the School of American Ballet, Concerto Barocco was premiered in 1941 by American Ballet Caravan (a touring group which later formed the nucleus of NYCB), and is set to music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Double Violin Concerto in D minor. “The musical score and the dancers themselves are the two greatest sources of inspiration,” explains Sidimus, “as they are in all of Balanchine’s choreographies.”

The 1930s were the height of the jazz age in New York, and Balanchine clearly showed his affinity for this form of music throughout the choreography for the ballet’s first movement, using “off” beats and intermittently employing a jazzy gestural language. (Not officially acknowledged by any source this author could find, a 1937 recording of a jazz rendition of the Double Violin Concerto featuring Eddie South, Stéphane Grappelli, and Django Reinhardt could conceivably have inspired the choreography.)

Permission to perform a Balanchine ballet is not granted to every company or school. “The technical level of the dancers dictates the Trust’s decision to allow the staging of a ballet,” says Sidimus, listing a few of the many challenges in Balanchine’s choreography: “being off balance, brilliant articulation of the feet, rapidity of movement, and an educated musicality.”

She is used to coaching dancers from diverse backgrounds, trained in many different methods. With students, “we start from a different point than with company dancers.” Her job as a repetiteur is to respect the dancers while protecting the authenticity and legacy of the Balanchine repertoire. She adds that this means “remaining positive, offering encouragement, but also being totally honest.”

A “sophisticated” musical understanding is key to performing all Balanchine ballets. “Music is not an accompaniment and you are not dancing TO the music. You ARE the music,” Sidimus tells the dancers during a rehearsal of Concerto Barocco at École supérieure. “Don’t listen to the music. Count!” she insists. Balanchine wanted dancers to hear what he heard, she explains, which means readjusting focus onto counts that follow the steps of the choreography, not the actual phrase structure of the music. Balanchine’s counts add an additional line of counterpoint to Bach’s masterful composition.

“Mr. B WAS music. He had it in his soul and he gave it to us,” she declares almost reverently. Other points emphasized and re-emphasized are the Balanchine approach to the fluidity, placement, and coordination of port de bras, the breadth and intention of all movements, and the sustained level of energy required of the dancers.

Sidimus has devoted a lifetime to studying and teaching the aesthetic of George Balanchine, with its inextricable link between music and choreography. “His genius was profound on many levels,” she says. To this day, she strives relentlessly, and with great humility, to share his genius with the next generation.